The Cosmic Serpent (11 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

“... DNA from afar, looking like a telephone cord ...”

Was it possible that no one had noticed the molecular aspect of the images? Well, yes, because I myself had often admired them and showed them to people to explain what the hallucinatory sphere looked like, and I had not noticed them either. My gaze had been as focalized as usual. I had not been able to see simultaneously molecular biology and shamanism, which our rational mind separatesâbut which could well overlap and correspond.

I was staggered. It seemed that no one had noticed the possible links between the “myths” of “primitive peoples” and molecular biology. No one had seen that the double helix had symbolized the life principle for thousands of years around the world. On the contrary, everything was upside down. It was said that hallucinations could in no way constitute a source of knowledge, that Indians had found their useful molecules by chance experimentation, and that their “myths” were precisely myths, bearing no relationship to the real knowledge discovered in laboratories.

At this point I remembered Michael Harner's story. Had he not said that this information was reserved for the dead and the dying? Suddenly, I was overcome with fear and felt the urge to share these ideas with someone else. I picked up the phone and called an old friend, who is also a writer. I quickly took him through the correspondences I had found during the day: the twins, the cosmic serpents, Eliade's ladders, Campbell's double helixes, as well as Amaringo's. Then I added: “There is a last correlation that is slightly less clear than the others. The spirits one sees in hallucinations are three-dimensional, sound-emitting images, and they speak a language made of three-dimensional, sound-emitting images. In other words, they are made of their own language, like DNA.”

There was a long silence on the other end of the line.

Then my friend said, “Yes, and like DNA they replicate themselves to relay their information.” “Wait,” I said, “I'm going to jot that down.” “Precisely,” he said, “instead of talking to me, you should be writing this down.”

18

18

I followed his advice, and it was in writing my notes on the relationship between the hallucinatory spirits made of language and DNA that I remembered the first verse of the first chapter of the Gospel according to John: “In the beginning was the

logos

Ӊthe word, the verb, the language.

logos

Ӊthe word, the verb, the language.

That night I had a hard time falling asleep.

Â

THE NEXT DAY I had to attend a professional meeting that bore no relationship to my research. I took advantage of the train ride to put things into perspective. I was feeling strange. On the one hand, entire blocks of intuition were pushing me to believe that the connection between DNA and shamanism was real. On the other hand, I was aware that this vision contradicted certain academic ideas, and that the links I had found so far were insufficient to trouble a strictly rational point of view.

Nonetheless, gazing out the train window at a random sample of the the Western world, I could not avoid noticing a kind of separation between human beings and all other species. We cut ourselves off by living in cement blocks, moving around in glass-and-metal bubbles, and spending a good part of our time watching other human beings on television. Outside, the pale light of an April sun was shining down on a suburb. I opened a newspaper and all I could find were pictures of human beings and articles about their activities. There was not a single article about another species.

Sitting on the train, I measured the paradox confronting me. I was a resolutely Western individual, and yet I was starting to believe in ideas that were not receivable from a rational point of view. This meant that I was going to have to find out more about DNA. Up to this point, I had only found biological correspondences in shamanism. It remained to be seen whether the contrary was also true, and whether there were shamanic correspondences in biology. More precisely, I needed to see whether shamanic notions about spirits corresponded to scientific notions about DNA. Basically I had only covered, at best, half the distance.

Even though my bookshelves were well stocked in anthropology and ecology, I owned no books about DNA or molecular biology; but I knew a colleague trained in both chemistry and literature who was going to be able to help me on that count.

Â

AFTER THE MEETING, toward the end of the afternoon, I went over to my colleague's house. He had generously allowed me to look through his books in his absence.

I entered his office, a big room with an entire wall occupied by bookshelves, turned on the light, and started browsing. The biology section contained, among others,

The double helix

by James Watson, the co-discoverer with Francis Crick of the structure of DNA. I flipped through this book, looking at the pictures with interest, and put it aside.

The double helix

by James Watson, the co-discoverer with Francis Crick of the structure of DNA. I flipped through this book, looking at the pictures with interest, and put it aside.

A little further along on the same shelf, I came upon a book by Francis Crick entitled

Life itself: Its origin and nature

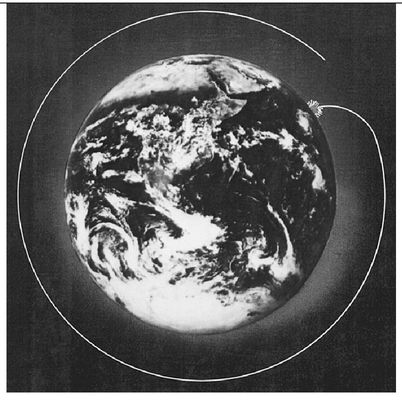

. I pulled it out and looked at its coverâand could not believe my eyes. It showed an image of the earth, seen from space, with a rather indistinct object coming from the cosmos and landing on it.

Life itself: Its origin and nature

. I pulled it out and looked at its coverâand could not believe my eyes. It showed an image of the earth, seen from space, with a rather indistinct object coming from the cosmos and landing on it.

Francis Crick, the Nobel Prize-winning co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, was suggesting that the molecule of life was of extraterrestrial originâin the same way that the “animist” peoples claimed that the vital principle was a serpent from the cosmos.

Cover of Crick (1981), reproduced with permission from Little, Brown & Co.

I had never heard of Crick's hypothesis, called “directed panspermia,” but I knew that I had just found a new correspondence between science and the complex formed by shamanism and mythology.

I sat down in the armchair and plunged into

Life itself: Its origin and nature

.

Life itself: Its origin and nature

.

Â

CRICK, writing in the early 1980s, criticizes the usual scientific theory on the origin of life, according to which a cell first appeared in the primitive soup through the random collisions of disorganized molecules. For Crick, this theory presents a major drawback: It is based on ideas conceived in the nineteenth century, long before molecular biology revealed that the basic mechanisms of life are identical for all species and are extremely complexâand when one calculates the probability of chance producing such complexity, one ends up with inconceivably small numbers.

The DNA molecule, which excels at stocking and duplicating information, is incapable of building itself on its own. Proteins do this, but they are incapable of reproducing themselves without the information contained in the DNA. Life, therefore, is a seemingly inescapable synthesis of these two molecular systems. Moving beyond the famous question of the chicken and the egg, Crick calculates the probability of the chance emergence of one single protein (which could then go on to build the first DNA molecule). In all living species, proteins are made up of exactly the same 20 amino acids, which are small molecules. The average protein is a long chain made up of approximately 200 amino acids, chosen from those 20, and strung together in the right order. According to the laws of combinatorials, there is 1 chance in 20 multiplied by itself 200 times for a single specific protein to emerge fortuitously. This figure, which can be written 20

200

, and which is roughly equivalent to 10

260

,

is enormously greater than the number of atoms in the observable universe

(estimated at 10

80

).

200

, and which is roughly equivalent to 10

260

,

is enormously greater than the number of atoms in the observable universe

(estimated at 10

80

).

These numbers are inconceivable for a human mind. It is not possible to imagine all the atoms of the observable universe and even less a figure that is billions of billions of billions of billions of billions (etc.) times greater. However, since the beginning of life on earth, the number of amino acid chains that could have been synthesized by chance can only represent a minute fraction of all the possibilities. According to Crick: “The great majority of sequences can never have been synthesized at all, at any time. These calculations take account only of the amino acid sequence. They do not allow for the fact that many sequences would probably not fold up satisfactorily into a stable, compact shape. What fraction of all possible sequences would do this is not known, though it is surmised to be fairly small.” Crick concludes that the organized complexity found at the cellular level “cannot have arisen by pure chance.”

The earth has existed for approximately 4.5 billion years. In the beginning it was merely a radioactive aggregate with a surface temperature reaching the melting point of metal. Not really a hospitable place for life. Yet there are fossils of single-celled beings that are approximately 3.5 billion years old. The existence of a single cell necessarily implies the presence of DNA, with its 4-letter “alphabet” (A, G, C, T), and of proteins, with their 20-letter “alphabet” (the 20 amino acids), as well as a “translation mechanism” between the twoâgiven that the instructions for the construction of proteins are coded in the language of DNA. Crick writes: “It is quite remarkable that such a mechanism exists at all and even more remarkable that every living cell, whether animal, plant or microbial, contains a version of it.”

19

19

Crick compares a protein to a paragraph made up of 200 letters lined up in the correct order. If the chances are infinitesimal for one

paragraph

to emerge in a billion years from a terrestrial soup, the probability of the fortuitous appearance, during the same period, of two

alphabets

and one

translation mechanism

is even smaller.

paragraph

to emerge in a billion years from a terrestrial soup, the probability of the fortuitous appearance, during the same period, of two

alphabets

and one

translation mechanism

is even smaller.

Â

WHEN I LOOKED UP from Crick's book, it was dark outside. I was feeling both astonished and elated. Like a myopic detective bent over a magnifying glass while following a trail, I had fallen into a bottomless hole. For months I had been trying to untangle the enigma of the hallucinatory knowledge of Western Amazonia's indigenous people, stubbornly searching for the hidden passage in the apparent dead end. I had only detected the DNA trail two weeks previously in Harner's book. Since then I had mainly developed the hypothesis along intuitive lines. My goal was certainly not to build a new theory on the origin of life; but there I wasâa poor anthropologist knowing barely how to swim, floating in a cosmic ocean filled with microscopic and bilingual serpents. I could see now that there might be links between science and shamanic, spiritual and mythological traditions, that seemed to have gone unnoticed, doubtless because of the fragmentation of Western knowledge.

With his book, Francis Crick provided a good example of this fragmentation. His mathematics were impeccable, and his reasoning crystalline; Crick was surely among twentieth-century rationality's finest. But he had not noticed that he was not the first to propose the idea of a snake-shaped vital principle of cosmic origin. All the peoples in the world who talk of a cosmic serpent have been saying as much for millennia. He had not seen it because the rational gaze is forever focalized and can examine only one thing at a time. It separates things to understand them, including the truly complementary. It is the gaze of the specialist, who sees the fine grain of a necessarily restricted field of vision. When Crick set about considering cosmogony from the serious perspective of molecular biology, he had long since put out of his analytical mind the myths of archaic peoples.

From my new point of view, Crick's scenario of “directed panspermia,” in which a spaceship transports DNA in the form of frozen bacteria across the immensities of the cosmos, seemed less likely than the idea of an omniscient and terrifying cosmic serpent of unimaginable power. After all, life as described by Crick was based on a miniature language that had not changed a letter in four billion years, while multiplying itself in an extreme diversity of species. The petals of a rose, Francis Crick's brain, and the coat of a virus are all built out of proteins made up of exactly the same 20 amino acids. A phenomenon capable of such creativity was surely not going to travel in a spaceship resembling those propelled containers imagined by human beings in the twentieth century.

Other books

And Then He Kissed Me by Southwick, Teresa

Valentine's Wishes by Daisy Banks

Shifters of Silver Peak: A Very Shifty Christmas by Georgette St. Clair

In the Bag by Kate Klise

Forged in Fire (The Forged Chronicles Book 3) by Alyssa Rose Ivy

Telling Lies to Alice by Laura Wilson

Privilege 1 - Privilege by Kate Brian

The Canning Kitchen by Amy Bronee

The Witch and the Dead by Heather Blake

Unintentional by Harkins, MK