The Cosmic Serpent (8 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

It had become clear to me that ayahuasqueros were somehow gaining access in their visions to verifiable information about plant properties. Therefore, I reasoned, the enigma of hallucinatory knowledge could be reduced to one question: Was this information coming from

inside

the human brain, as the scientific point of view would have it, or from the

outside

world of plants, as shamans claimed?

inside

the human brain, as the scientific point of view would have it, or from the

outside

world of plants, as shamans claimed?

Both of these perspectives seemed to present advantages and drawbacks.

On the one hand, the similarity between the molecular profiles of the natural hallucinogens and of serotonin seemed well and truly to indicate that these substances work like keys fitting into the same lock

inside

the brain. However, I could not agree with the scientific position according to which hallucinations are merely discharges of images stocked in compartments of the subconscious memory. I was convinced that the enormous fluorescent snakes that I had seen thanks to ayahuasca did not correspond in any way to anything that I could have dreamed of, even in my most extreme nightmares. Furthermore, the speed and coherence of some of the hallucinatory images exceeded by many degrees the best rock videos, and I knew that I could not possibly have filmed them.

9

inside

the brain. However, I could not agree with the scientific position according to which hallucinations are merely discharges of images stocked in compartments of the subconscious memory. I was convinced that the enormous fluorescent snakes that I had seen thanks to ayahuasca did not correspond in any way to anything that I could have dreamed of, even in my most extreme nightmares. Furthermore, the speed and coherence of some of the hallucinatory images exceeded by many degrees the best rock videos, and I knew that I could not possibly have filmed them.

9

On the other hand, I was finding it increasingly easy to suspend disbelief and consider the indigenous point of view as potentially correct. After all, there were all kinds of gaps and contradictions in the scientific knowledge of hallucinogens, which had at first seemed so reliable: Scientists do not know how these substances affect our consciousness, nor have they studied true hallucinogens in any detail. It no longer seemed unreasonable to me to consider that the information about the molecular content of plants could truly come from the plants themselves, just as ayahuasqueros claimed. However, I failed to see how this could work concretely.

With these thoughts in mind, I interrupted my stroll and sat down, resting my back against a big tree. Then I tried to enter into communication with it. I closed my eyes and breathed in the damp vegetal scent in the air. I waited for a form of communication to appear on my mental screenâbut I ended up perceiving nothing more than the agreeable feeling of immersion in sunshine and fertile nature.

After about ten minutes, I stood up and resumed walking. Suddenly my thoughts turned again to stereograms. Maybe I would find the answer by looking at both perspectives simultaneously, with one eye on science and the other on shamanism. The solution would therefore consist in posing the question differently: It was not a matter of asking whether the source of hallucinations is internal

or

external, but of considering that it might be both at the same time. I could not see how this idea would work in practice, but I liked it because it reconciled two points of view that were apparently divergent.

or

external, but of considering that it might be both at the same time. I could not see how this idea would work in practice, but I liked it because it reconciled two points of view that were apparently divergent.

The path I was following led to a crystalline cascade gushing out of a limestone cliff. The water was sparkling and tasted like champagne.

Â

THE NEXT DAY I returned to my office with renewed energy. All I had to do was classify my reading notes on Amazonian shamanism and then I could start writing. However, before getting down to this task, I decided to spend a day following my fancy, freely paging through the piles of articles and notes that I had accumulated over the months.

In reading the literature on Amazonian shamanism, I had noticed that the personal experience of anthropologists with indigenous hallucinogens was a gray zone. I knew the problem well for having skirted around it myself in my own writings. One of the categories in my reading notes was called “Anthropologists and Ayahuasca.” I consulted the card corresponding to this category, which I had filled out over the course of my investigation, and noted that the first subjective description of an ayahuasca experience by an anthropologist was published in 1968âwhereas several botanists had written up similar experiences a hundred years previously.

10

10

The anthropologist in question was Michael Harner. He had devoted ten lines to his own experience in the middle of an academic article: “For several hours after drinking the brew, I found myself, although awake, in a world literally beyond my wildest dreams. I met bird-headed people, as well as dragon-like creatures who explained that they were the true gods of this world. I enlisted the services of other spirit helpers in attempting to fly through the far reaches of the Galaxy. Transported into a trance where the supernatural seemed natural, I realized that anthropologists, including myself, had profoundly underestimated the importance of the drug in affecting native ideology.”

11

11

At first Michael Harner pursued an enviable career, teaching in reputable universities and editing a book on shamanism for Oxford University Press. Later, however, he alienated a good portion of his colleagues by publishing a popular manual on a series of shamanic techniques based on visualization and the use of drums. One anthropologist called it “a project deserving criticism given M. Harner's total ignorance about shamanism.”

12

In brief, Harner's work was generally discredited.

12

In brief, Harner's work was generally discredited.

I must admit that I had assimilated some of these prejudices. At the beginning of my investigation, I had only read through Harner's manual quickly, simply noting that the first chapter contained a detailed description of his first ayahuasca experience, which took up ten pages this time, instead of ten lines. In fact, I had not paid particular attention to its content.

So, for pleasure and out of curiosity, I decided to go over Harner's account again. It was in reading this literally fantastic narrative that I stumbled on a key clue that was to change the course of my investigation.

Harner explains that in the early 1960s, he went to the Peruvian Amazon to study the culture of the Conibo Indians. After a year or so he had made little headway in understanding their religious system when the Conibo told him that if he really wanted to learn, he had to drink ayahuasca. Harner accepted not without fear, because the people had warned him that the experience was terrifying. The following evening, under the strict supervision of his indigenous friends, he drank the equivalent of a third of a bottle. After several minutes he found himself falling into a world of true hallucinations. After arriving in a celestial cavern where “a supernatural carnival of demons” was in full swing, he saw two strange boats floating through the air that combined to form “a huge dragon-headed prow, not unlike that of a Viking ship.” On the deck, he could make out “large numbers of people with the heads of blue jays and the bodies of humans, not unlike the bird-headed gods of ancient Egyptian tomb paintings.”

After multiple episodes, which would be too long to describe here, Harner became convinced that he was dying. He tried calling out to his Conibo friends for an antidote without managing to pronounce a word. Then he saw that his visions emanated from “giant reptilian creatures” resting at the lowest depths of his brain. These creatures began projecting scenes in front of his eyes, while informing him that this information was reserved for the dying and the dead: “First they showed me the planet Earth as it was eons ago, before there was any life on it. I saw an ocean, barren land, and a bright blue sky. Then black specks dropped from the sky by the hundreds and landed in front of me on the barren landscape. I could see the âspecks' were actually large, shiny, black creatures with stubby pterodactyl-like wings and huge whale-like bodies.... They explained to me in a kind of thought language that they were fleeing from something out in space. They had come to the planet Earth to escape their enemy. The creatures then showed me how they had created life on the planet in order to hide within the multitudinous forms and thus disguise their presence. Before me, the magnificence of plant and animal creation and speciationâhundreds of millions of years of activityâtook place on a scale and with a vividness impossible to describe. I learned that the dragon-like creatures were thus inside all forms of life, including man.”

At this point in his account, Harner writes in a footnote at the bottom of the page: “In retrospect one could say they were almost like DNA, although at that time, 1961, I knew nothing of DNA.”

13

13

I paused. I had not paid attention to this footnote previously. There was indeed DNA

inside

the human brain, as well as in the

outside

world of plants, given that the molecule of life containing genetic information is the same for all species. DNA could thus be considered a source of information that is both external and internalâin other words, precisely what I had been trying to imagine the previous day in the forest.

inside

the human brain, as well as in the

outside

world of plants, given that the molecule of life containing genetic information is the same for all species. DNA could thus be considered a source of information that is both external and internalâin other words, precisely what I had been trying to imagine the previous day in the forest.

I plunged back into Harner's book, but found no further mention of DNA. However, a few pages on, Harner notes that “dragon” and “serpent” are synonymous. This made me think that the double helix of DNA resembled, in its

form,

two entwined serpents.

form,

two entwined serpents.

Â

AFTER LUNCH, I returned to the office with a strange feeling. The reptilian creatures that Harner had seen in his brain reminded me of something, but I could not say what. It had to be a text that I had read and that was in one of the numerous piles of documents and notes spread out over the floor. I consulted the “Brain” pile, in which I had placed the articles on the neurological aspects of consciousness, but I found no trace of reptiles. After rummaging around for a while, I put my hand on an article called “Brain and mind in Desana shamanism” by Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff.

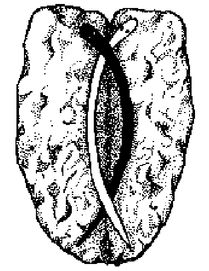

I had ordered a copy of this article from the library during my readings on the brain. Knowing from Reichel-Dolmatoff's numerous publications that the Desana of the Colombian Amazon were regular ayahuasca users, I had been curious to learn about their point of view on the physiology of consciousness. But the first time I had read the article, it had seemed rather esoteric, and I had relegated it to a secondary pile. This time, paging through it, I was stopped by a Desana drawing of a human brain with a snake lodged between the two hemispheres (

see top of page 57

).

see top of page 57

).

I read the text above the drawing and learned that the Desana consider the fissure occupied by the reptile to be a “depression that was formed in the beginning of time (of mythical and embryological time) by the cosmic anaconda. Near the head of the serpent is a hexagonal rock crystal, just outside the brain; it is there where a particle of solar energy resides and irradiates the brain.”

14

14

Several pages further into the article, I came upon a second drawing, this time with two snakes (

see top of page 58

).

see top of page 58

).

The human brain. The left hemisphere is referred to as Side One, and the right as Side Two. The fissure is occupied by an anaconda. (Redrawn from Desana sketches.) From Reichel-Dolmatoff (1981, p. 81).

According to Reichel-Dolmatoff, the drawing on page 58 shows that within the fissure “two intertwined snakes are lying, a giant anaconda (

Eunectes murinus

) and a rainbow boa (

Epicrates cenchria

), a large river snake of dark dull colors and an equally large land snake of spectacular bright colors. In Desana shamanism these two serpents symbolize a female and male principle, a mother and a father image, water and land ...; in brief, they represent a concept of binary opposition which has to be overcome in order to achieve individual awareness and integration. The snakes are imagined as spiralling rhythmically in a swaying motion from one side to another.”

15

Eunectes murinus

) and a rainbow boa (

Epicrates cenchria

), a large river snake of dark dull colors and an equally large land snake of spectacular bright colors. In Desana shamanism these two serpents symbolize a female and male principle, a mother and a father image, water and land ...; in brief, they represent a concept of binary opposition which has to be overcome in order to achieve individual awareness and integration. The snakes are imagined as spiralling rhythmically in a swaying motion from one side to another.”

15

Intrigued, I began reading Reichel-Dolmatoff's article from the beginning. In the first pages he provides a sketch of the Desana's main cosmological beliefs. My eyes stopped on the follow-ing sentence: “The Desana say that in the beginning of time their ancestors arrived in canoes shaped like huge serpents.”

16

16

The human brain. The fissure is occupied by an anaconda and a rainbow boa. (Redrawn from Desana sketches.) From Reichel-Dolmatoff (1981, p. 88).

Other books

Geography by Sophie Cunningham

Policia Sideral by George H. White

Next To You by Sandra Antonelli

Ecko Rising by Danie Ware

Blood and Bone by Austin Camacho

The Second Life of Abigail Walker by Frances O'Roark Dowell

When Lightning Strikes by Brenda Novak

Chance of Rain by Lin, Amber

Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon?, Vol. 4 by Fujino Omori

Strictly Off Limits (Jade's College Diaries) by Spears, Crystal D.