The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (8 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

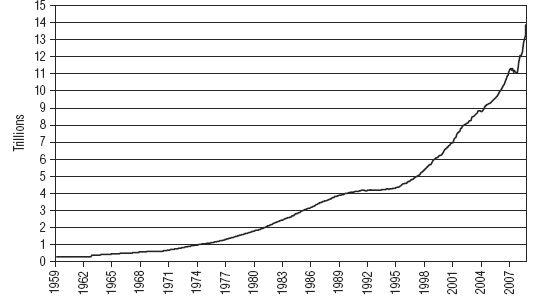

On the following page is another exponential chart—the U.S. money supply, which has been compounding at incredible rates ranging between 5 and 18 percent per year (

Figure 5.7

).

Figure 5.7

Total Money Stock (M3)

This was the widest measure of money before its reporting was discontinued by the Federal Reserve. M3 money included cash, checking and savings accounts, time deposits, and Eurodollars.

Source:

Federal Reserve.

These are just a few examples. We could review hundreds of separate charts of things as diverse as the length of paved roads in the world, species loss, water use, retail outlets, miles traveled, or widgets sold, and we’d see the same sorts of charts with lines that curve sharply up from left to right.

The point here is that you are literally surrounded by examples of exponential growth found in the realms of the economy, energy, and the environment. Far from being a rare exception, they are the norm, and because they dominate your experience and will shape the future, you need to pay attention to them.

The Rule of 70

As I said before, anything that is growing by some percentage is growing exponentially. Another handy way to think about this is to be able to quickly calculate how long it will take for something to double in size. For example, if you are earning 5 percent on an investment, the question would be,

How long will it be before a $1,000 investment has doubled in size to $2,000?

The answer is surprisingly easy to determine using something called the “Rule of 70.”

1

To calculate how long it will be before something doubles, all we need to do is divide the percentage rate of growth into the number 70. So if our investment were growing at 5 percent

per year

, then it would double in 14 years (70 divided by 5 equals 14). Similarly if something is growing by 5 percent

per month

, then it will double in 14 months.

How long before something growing at 10 percent per year will double? Easy; 70 divided by 10 is 7, so the answer is 7 years.

Here’s a trick question:

Suppose something has been growing at 10 percent per year for 28 years. How much has it grown?

Some people intuitively guess eight times larger (2 + 2 + 2 + 2 = 8), or four separate doublings over each of the four 7 year periods in the example, but the answer is sixteen, because each doubling builds off of the last (2 ⇒ 4 ⇒ 8 ⇒ 16). Two doubles to four, which doubles to eight, which doubles to sixteen, which is twice as large as intuition might suggest.

Here’s where we might use that knowledge in real life. You might have read about the fact that China’s energy consumption grew at a rate of slightly more than 8 percent between 2000 and 2009, which perhaps sounds somewhat tame. Using the Rule of 70, however, we discover that China is doubling the amount of energy it uses roughly every 9 years, as was confirmed by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2010.

7

After 9 years of 8 percent growth, you’re not using just a little bit more energy, but 100 percent more. If a country has 500 coal-fired electricity plants today, after 9 years of 8 percent growth it will need 1000 such plants.

If this seems rather dramatic and nontrivial to you, you’re right. Time for another trick question about doublings:

Which is larger in size, the amount of energy China used over just the past 9 years (its most recent doubling time), or the amount of energy China has used throughout

all

of history?

The intuitive answer is that the total amount of energy consumed throughout China’s thousands of years of history is far larger than the amount consumed over the past 9 years, but the correct answer is that the most recent doubling is larger than all the prior doublings put together.

8

This is a general truth about doublings, not China in particular, and applies to anything and everything that has gone through a doubling cycle. To make sense of this preposterous claim, let’s use the legend of the mathematician who invented the game of chess for a king. So pleased was the king with this invention that he asked the mathematician to name his reward. The mathematician made a request that seemed modest: to be given a single grain of rice for the first square on the board, two grains for the second square, four grains for the third square, and so on. The king agreed, and foolishly committed to a sum of rice that was approximately 750 times larger than the entire annual worldwide harvest of rice in 2009. That’s what 64 doublings will get you.

Note that the first square had one grain of rice placed upon it, while the next square, the first doubling, got two grains. Here on the very first doubling, we can observe that more rice was placed upon the board than was already on the board; two compared to one. That is, the doubling was larger in size than all of the grains that had come before it. And on the next doubling, when we place four grains upon the board, we see that these four grains of rice are more numerous than the three grains (1 + 2) already upon the board from all the prior doublings. And at the next doubling we place eight grains on the board, which is a larger total than the seven that are already upon it (1 + 2 + 4). And so on. In every doubling, we’ll find that the most recent doubling is larger in size than all of the prior doublings put together. That’s one of the less intuitive but more important features of doublings. Each doubling is larger than all the ones that came before

put together

.

So if your town administrators are targeting, say, 5 percent growth, what they’re really saying is that in 14 years time they want to have more than twice as much of everything in the town than it currently has. More than twice as many people, sewage treatment plants, schools, congestion, electrical and water demand, and everything else that a town needs. Not a few more, but

more than twice as many

.

Your Exponential World

The reason we took this departure into discussing exponential growth and doubling times is that you happen to be completely surrounded by examples of exponential growth. And your future, like it or not, will be heavily shaped by their presence.

As you read the rest of this book, it will be helpful to continue to recall these three concepts related to exponential growth and doublings:

1.

Speeding up

. Time really gets compressed toward the end of the exponential phase of growth.2.

Turning the corner

. This is a very real and extremely important event in systems with limits.3.

More than double

. Each doubling equals more than all of the prior ones combined.

This information is going to be especially critical when we talk about the idea that our economy, our money system, and all of our associated institutions are fundamentally predicated on exponential growth. As we’ll see, it’s not just any type of growth that our money system requires, but

exponential

growth.

Up until recently, that has been a fine and workable model, but once we introduce the idea of resource limits into our collective story of growth (in other words, once we know just how big is the stadium in which we’re all sitting), we quickly discover some serious flaws in our current narrative. It turns out that the economy does not exist in a vacuum, and it does not have the power to create reality. The economy is really just a reflection of our access to abundant energy and other concentrated resources that we can transform into useful products and services. As long as those resources can continue to be extracted from the earth in ever-increasing quantities, then our economic model is safe and sound. And that is where the trouble in this story begins.

1

Some use “the Rule of 72,” which is more accurate in some circumstances, but less easy to calculate in our heads, so we’ll stick to 70 for now, as it is perfectly accurate for our purposes.

CHAPTER 6

An Inconvenient Lie

The Truth about Growth

All truth passes through three stages. First, it is ridiculed. Second, it is violently opposed. Third, it is accepted as being self-evident.

—Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860)

Unless we are careful, we might accidentally pursue growth when what we really are seeking is prosperity. The problem is that prosperity has so often accompanied growth that it has become easy to confuse the two.

Growth appears to solve many problems. Growth creates jobs and adds new money to strained government coffers. At the same time that growth occurs, new opportunities often arise. Growth is so central to our economic models and thinking that many economists will, with completely straight faces, refer to recessions as periods of “negative growth.” If that doesn’t reveal a bias toward growth, I don’t know what does. It’s impossible to listen to a presidential press conference on the economy without hearing about growth and how important it is that we create more of it. Economic growth is unquestionably assumed to be desirable, and that’s pretty much all there is to the story.

Anybody who believes exponential growth can go on forever in a finite world is either a madman or an economist.

—Kenneth Boulding (1910–1993)

1

The type of growth upon which our economy depends, exponential growth, is completely unsustainable and will therefore someday stop. Nothing can grow forever, at least nothing that consumes finite resources to fuel its growth. It is my view that this shift to no growth or even negative growth (to use that odd economic term) will happen within the next 20 years, although a transition could happen much sooner, if it didn’t already begin in 2008. Whenever it happens to occur, it will be destructive to wealth and unpleasant for most people. This means that the paradigm of economic growth, along with its presumed necessity and even desirability, needs to be hauled out into the bright light of day and carefully examined.

The imperative for growth is only very rarely questioned, and it’s usually reported in the news as though it were just another necessary component of life. So few people ever question the importance of economic growth that it has become culturally elevated to the same top tier of the winner’s podium as other “essentials” such as supermarkets and gasoline stations. From this, we might be led to conclude that economic growth is truly an essential feature of our economic landscape.

To give you a good example of this assumption, look at how embedded the concept of growth is in this short passage in a 2010

New York Times

editorial by Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner:

The process of repair means economic

growth

will come slower than we would like. But despite these challenges, there is good news to report:

- Exports are booming because American companies are very competitive and lead the world in many high-tech industries.

- Private job

growth

has returned—not as fast as we would like, but at an earlier stage of this recovery than in the last two recoveries. Manufacturing has generated 136,000 new jobs in the past six months.- Businesses have repaired their balance sheets and are now in a strong financial position to reinvest and

grow

.- Major banks, forced by the stress tests to raise capital and open their books, are stronger and more competitive. Now, as businesses expand again, our banks are better positioned to finance

growth

.

By taking aggressive action to fix the financial system, reduce

growth

in health care costs and improve education, we have put the American economy on a firmer foundation for future

growth.

2

The word

growth

appears six times in eight sentences, while the words

expand

and

booming

have cameo roles. The message is clear: Growth is what we are after.

Businesses constantly seek to grow, local municipalities have growth targets, states and provinces covet high growth, and the federal government seeks to promote economic growth. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve (“the Fed”) has full employment as one of its core mandates: Since the population is constantly growing and new jobs come from an expanding economy, economic growth is a logical mandate of the central bank. The Fed also has a minimum inflation target of roughly 2 percent, which means that growth of the money supply is a central bank target. But wait a minute . . . since the inflation target is expressed as a percentage, it means that exponential monetary growth is an express goal of the Federal Reserve. How did economic growth come to be so deeply embedded in our language, ideas, and philosophies?

For a long time, longer than anyone reading this has been alive, economic growth has been synonymous with increasing prosperity. By prosperity, I mean a higher standard of living defined by more of everything, easier access to all of the conveniences, luxuries, products, and services that define modern life, and plentiful and varied jobs and opportunities.

The Industrial Revolution brought an explosion of both growth and prosperity. When you read today about how many people live below the poverty line, it’s helpful to realize that nearly every citizen of any developed country today lives at a level of prosperity and comfort that is equivalent to a level enjoyed only by the wealthy in the not-too-distant past. If growth delivered this prosperity, then it is easy to understand why growth would be revered and sought. If growth brings prosperity, then let’s have growth! From there, it’s just a hop, skip, and a jump to the measurement and pursuit of economic growth as an end all its own, and that is where we find ourselves today.

But is it actually true that growth equals prosperity? What if it doesn’t?

Thought about one way, we might conclude that growth is actually a consequence of and dependent on the presence of surplus. For example, our bodies will only grow if they have a surplus of food. With an exact match between calories consumed and calories burned, a body will neither gain nor lose weight. A pond will only grow deeper if more water is flowing in than flowing out. With a deficit of food or water, growth of bodies and ponds will cease and then reverse. Growth in these examples is dependent on surplus.

But exactly what sort of a “surplus” is economic growth dependent upon? It’s not a surplus of money, or labor, or ideas, although each of those can be an important contributing factor. All economic growth is dependent on what economist Julian Simon called “the master resource”—energy.

3

We’ll have much more to say about that later on, but for now we’ll just make the claim that without energy nothing else is possible.

Prosperity is also dependent on surplus. Here is an example: Imagine a family of four with a yearly income of $40,000 that is sufficient to precisely cover life’s necessities. For this family, there is a perfect balance between income and outflow. Now suppose that good fortune befalls them and they receive a 10 percent boost to their household income. This windfall will allow them to

either

afford to have one more child (i.e., grow)

or

to shower a little bit more spending on each person (i.e., economic prosperity), but they can’t do both. There’s only enough surplus money in this example to do one of those things, so they have to choose between additional growth and more prosperity. When the amount of surplus is limited, either growth

or

prosperity can be increased, but not both at once. “Funding” both growth and prosperity at the same time can only happen during periods when there’s enough surplus to fund both.

From this simple example, we can tease out a very basic but profound concept:

Growth does not equal prosperity

. For the past few hundred years, we’ve been lulled into linking the two concepts, because there was always sufficient surplus energy that we could have both growth

and

prosperity at the same time. But that was largely an artifact of a fossil fuel bonanza, not an intrinsic attribute of growth.

If growth in structures and population could bring prosperity, then Quito, Ecuador, and Calcutta, India, would be among the most prosperous places on earth. But they’re not. If growth in a nation’s money supply brought prosperity, then Zimbabwe would have been the wealthiest country on the planet in 2010. But clearly it wasn’t. Growth alone does not bring prosperity, and, worse, growth can steal from prosperity if there aren’t enough resources to support both.

In wealthier countries where an energy and resource bonanza can provide enough surplus for both growth and prosperity, we see both. In poorer countries that can only afford to fund one or the other, we only see (population) growth. For the past 200 years, the developed world has not had to choose between growth and prosperity—it could have both, and it did.

As long as energy supplies can continue to grow forever, there is no conflict between growth and prosperity, and we’ll never have to choose between the two. But someday total energy will decline, and the world will discover that a dogged insistence on growth will diminish its prosperity. Unless we’re careful, there will come a time when 100 percent of our surplus money or energy will be used to simply grow, and the result will be stagnant and then declining prosperity.

The inconvenient truth about growth, then, is that it only really serves us if there is sufficient surplus to fund both growth

and

prosperity. Once there is not enough surplus for both, it becomes a contest between the two. The risk is that our slavish, unexamined devotion to growth, so deeply embedded within our language and customs that it rarely surfaces for examination, will dictate that growth is what we seek, rather than the prosperity that we actually desire. For politicians and others who are fully invested in the status quo, seeking economic growth is on par with supporting motherhood and apple pie. For them, it’s the path of least resistance, but for the rest of us, it’s now the path with the highest risk because it may very well lead to a future of vastly reduced prosperity.

The most important decision of our time concerns where we direct our remaining energy and other natural surpluses. Choices must be made. We can either spend our surplus resources toward trying to figure out how to simply grow, or we can spend them toward increasing and enhancing our prosperity. We’re rapidly approaching the time when we will no longer be able to do both, if that time has not already arrived. My strongest preference would be to see continued progress in energy efficiency, medical technology, and other significant advancement opportunities that modern society can offer. These are a few of the things that we place at risk if we allow ourselves to do what is easy—that is, to take the path of least resistance and simply grow—instead of doing what is right, which would be to intelligently dedicate our remaining energy surplus to a more prosperous future.