The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (10 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

With this new deposit, the bank now has a fresh $900 deposit against which it can loan out 90 percent, which works out to $810. So it gets busy finding somebody who wants to borrow $810 and loans them the money, which then gets spent and (surprise!) redeposited in the same bank. So now another fresh deposit of $810 is available to create a loan of $729 (which is 90 percent of $810), and so on, until we finally discover that the original $1,000 deposit has mushroomed into a total of $10,000 in various bank accounts. This is how fractional reserve banking can, and does, turn $1,000 into $10,000.

Is this all real money? You bet it is, especially if it’s in

your

bank account. But if you were paying close attention, you would realize that there’s more than just money in those bank accounts. The bank records the existence of $10,000 in various accounts, but it also has the notes to $9,000 in debts, which must be paid back. The

original

$1,000 is now entirely held in reserve by the bank, but every

new

dollar in the town, all $9,000, was merely loaned into existence and is now “backed” only by an equivalent amount of debt. How is your mind doing? Is it repelled yet?

You might also notice here that if everybody who had money at the bank, all $10,000 dollars of it, tried to take the money out at once, the bank would not be able to pay it out because . . . well, they wouldn’t have it. The bank would only have $1,000 sitting in reserve. Period. You might also notice that this mechanism of creating new money out of new deposits works great as long as nobody defaults on a loan. If and when that happens, things get tricky. But that’s another story for another time.

For now, I want you to understand that money is loaned into existence. When loans are made, money appears as if by magic. Conversely, when loans are paid back, money disappears, as the debts and the money cancel each other out when the loans are paid back. This is how money is created. I invite you to verify this for yourself. One place you can do that is the Federal Reserve, which has published all of this information in handy comic book form, which you can order from them for free.

4

You may have noticed that I left out something very important in the course of this story: interest. Where does the money come from to pay the interest on all the loans? If all the loans are paid back without interest, we can undo the entire string of transactions, but when we factor in interest, suddenly there’s not enough money to pay back all the loans.

1

So where does the money come from to pay back the interest? And where did that original $1,000 come from? We can clear up both mysteries by traveling to the headwaters of the money river.

The Fed

Even though you might have gotten a loan from Bank of America, creating money in the process, the dollars you received don’t say “Bank of America Note” on them; they say “Federal Reserve Note.” To find out where all money originally comes from, we need to spend a little time understanding how the Federal Reserve creates money.

Chartered by Congress in 1913 to manage the nation’s money supply, the Federal Reserve (a.k.a. “the Fed”) has complete and unilateral discretion to decide when and how much money is made available to the banking system, and by extension the entire economy.

But the Fed doesn’t just print up a bunch of money and send it out in trucks; it

lends

the money into existence. After all, it is a bank. The process works like this: Suppose the U.S. government wishes to spend more money than it has. Perhaps it has done something really historically foolish, like cutting taxes while conducting two wars at the same time, and finds itself short of money.

Now, having abdicated its monetary responsibilities to a third party (the Fed), the U.S. government can’t create any money, so the request for additional spending money by Congress gets routed through the Treasury Department, which, it turns out, rarely has more than a couple of weeks of cash on hand (if that) already earmarked for spending that was put into motion months or even years ago.

So in order to raise the desired cash, the Treasury Department will print up a stack of Treasury bonds (or bills or notes, which are essentially all the same things with different maturities). A bond has a “face value,” which is the amount that it will be sold for, and it has a stated rate of interest that it will pay the holder. So if you bought a bond with a $100 face value that pays a rate of interest of 5 percent, then you would pay $100 for this bond but get $105 back in a year, representing your original $100 plus $5 in interest.

Treasury bonds, bills, and notes are sold in regularly scheduled auctions and are mainly purchased by banks, other large financial institutions, or the central banks of other countries. So if a batch of bonds with a face value of $1 billion is sold at auction, then that $1 billion lands in the Treasury’s coffers, where it is then available to the U.S. government to spend. Assuming these are Treasury Notes with a one year maturity, in a year the Treasury Department will return all $1 billion to the purchasers of those bonds, plus an amount equal to whatever the rate of interest happened to be.

So far no new money has yet been created. Treasury bonds are bought with money that already exists. The question remains,

Where does new money come from?

New money, a.k.a. “hot money,” comes into being when the Federal Reserve buys a Treasury bond from a bank. When the Fed does this, it simply transfers money in the amount of the bond to the other bank and takes possession of the bond. The bond is swapped for money.

But where did

that

money come from? It was created out of thin air, as the Fed literally creates money when it “buys” this debt.

Don’t believe me? Here’s a quote from a Federal Reserve publication titled “Putting it Simply”:

When you or I write a check, there must be sufficient funds in our account to cover the check, but when the Federal Reserve writes a check, there is no bank deposit on which that check is drawn. When the Federal Reserve writes a check, it is creating money.

5

Now

that

is an extraordinary power. Whereas you or I need to work (i.e., expend human labor) to obtain money, and then place it at risk to have it grow, the Federal Reserve simply prints up as much as it deems prudent and then loans it out, with interest.

The answer to how money originally comes into existence is very simple: It’s loaned out of thin air by the Fed.

Is your mind repelled yet?

Two Kinds of Money—One Exponential System

So now we know that there are two kinds of money out there. The first is bank credit, which is money that is loaned into existence, as we saw in the first bank example. Bank credit comes with an equal and offsetting amount of debt associated with it, consisting of a principal balance and a rate of interest that must be paid on that balance. Because this money, which is also created out of thin air, accumulates interest charges, it promotes the growth of the money supply, even though the principal balance must be paid back. The interest represents money that accumulates over time, and as long as everything is working according to plan, it does so exponentially because it accumulates on a percentage basis.

The second type of money is also printed out of thin air, but it is created by the Fed, and it forms what is known as the “base money supply” of the nation. If you’re thinking of “base” as in a solid foundation, as in permanent, then you have the right mental image. This money forms the base of all other loans, which, as we saw earlier, can be multiplied fantastically due to the miracle of fractional reserve banking. Base money, too, is loaned into existence, and a quick glance at the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet reveals nothing but various types and forms of debts that it has swapped for thin air money. Together these two forms of money (base and credit) conspire to create a money system that will expand exponentially. Loaning money into existence, at a rate of interest, virtually assures this outcome.

2

The very mechanisms of our money system promote and even demand the exponential growth of money and debt. If the deconstructed workings of the lending and interest cycle are not enough to make the case, then perhaps some empirical data will do the trick.

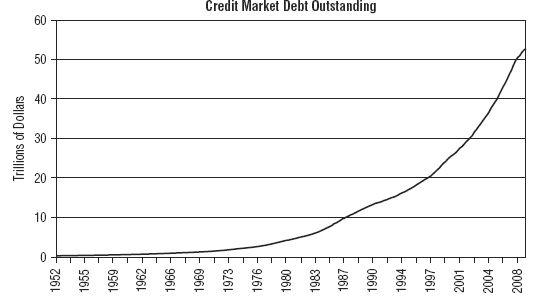

In

Figure 7.1

, we see a chart of the total credit market debt in the United States from 1952 to 2008.

3

Figure 7.1

Total Credit Market Debt

All forms of debt are represented here: federal, state, municipal, corporate, and household.

Source:

Federal Reserve.

Here again, we see a nearly perfect hockey stick, but this example is of debt. Even without knowing all of the details that underlie money creation and policy, we could simply observe the exponential features of this chart and readily form a quite strong hypothesis that we’re studying an exponential system.

The fact that our money/debt system is growing exponentially is an exceptionally important observation, and one that has enormous bearing on how claims on wealth will be settled in the future. Remember, money is simply a claim on wealth. When money is exponentially accumulating (growing), it carries both an implicit and explicit wager that the economy will be exponentially larger in the future. After all, if the economic future turns out to be smaller, but there is exponentially more money and debt floating around, then all of those monetary claims will be chasing a smaller stack of goods, which means they will be worth less than they currently are. Therefore, when we see money and debt growing exponentially, our very first task should be to assess whether the economy is growing similarly. If not, then we might rationally question whether paper claims against wealth are the best way to store wealth. Perhaps it might make more sense to hold wealth itself, not claims against it. We will go into more detail about wealth in Chapter 9 (

What Is Wealth?

).

What we’ve just learned about money allows us to formulate two more extremely important concepts. The first is that all dollars are backed by debt. At the level of the local bank, all new money is loaned into existence. At the Federal Reserve level, money is simply manufactured out of thin air and then exchanged for interest-paying government debt. In both cases, the money is backed by debt—debt that pays interest.

Because our debt-based money system is always continually growing by some percentage, it is an exponential system by its very design. A corollary of this is that the amount of debt in the system will always exceed the amount of money.

4

I’m not going to cast judgment on this system and say whether it’s good or bad. It simply is what it is. By understanding its design, though, you’ll be better equipped to understand that the potential range of future outcomes for our economy are not limitless; rather, they are bounded by the rules of the system.

All of which leads us to another concept, the idea that perpetual expansion is a

requirement

of modern banking. Without a continuous expansion of the money supply (via credit expansion), all sorts of trouble emerges within the modern banking system, including debt defaults, which are the Achilles heel of a leveraged, debt-based money system.

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that this requirement to expand is written down somewhere, neither etched in legal stone in the basement of the world’s centers of power nor forever enshrined in Google’s search cloud. Instead, I use the word “requirement” in the same way that your body requires oxygen. Yes, the system can operate for brief periods without it, but it’s a lot happier and more productive with it.