The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (11 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

By understanding the requirement for continual expansion, we are in a position to illuminate the future and make informed decisions about what is likely to transpire.

1

Some argue that there is enough money to pay back all of the loans, but this is only true under highly unrealistic conditions, where every loan creates goods or services that are bought by the bank or bank shareholders, who buy them with interest payments that are perfectly recycled to the very same people who took out the loans. I call this the “theory of perfect interest flows.” While theoretically possible, it is not at all realistic and is therefore something of an intellectual parlor trick. Under this model, nobody can ever take out a purely consumptive loan, undertake a failed business venture, or save money without spending it. As soon as any of these three things happens (and they happen all the time in real life), there’s not enough money to pay off all the loans. Suffice it to say that this vision of “immaculate interest flows” is an interesting thought experiment, but it is not at all useful in understanding how the system operates in practice and is therefore not terribly helpful as a way of understanding the current situation or future risks.

2

I know that I have skipped over a number of details, some of them quite important for the sake of accuracy, but we’ve covered enough of the process for the purposes of this book. For more complete explanations please see the

Crash Course

at

www.chrismartenson.com/crashcourse

.

3

This chart uses the M3 data series from the Fed up until March of 2008, when it was discontinued. No further M3 data is available from the Fed, although a number of private firms still construct and follow this data series. Using their data to continue the graph does not alter the conclusions; the money series displays nearly perfect exponential behavior.

4

Again, for those who prefer data over theory, consider that in the United States at the end of 2009, there were more than $52 trillion of total credit market debt, but only approximately $14 trillion of money (and money equivalents). This means that we now have far more debt than money.

CHAPTER 8

Problems and Predicaments

John Michael Greer makes a very important distinction between two common but critical words: “problems” and “predicaments.”

1

This terminology is important, especially in an urgent situation, because knowing whether you’re facing a problem or a predicament is integral to shaping your understanding of and response to the situation.

The distinction boils down to this: Problems have solutions; predicaments have outcomes. A solution to a problem fixes it, returning all to its original condition. Flat tires get fixed, revenues recover, and bones mend. Once a suitable solution can be found and made to work, a problem can be solved.

A predicament, by contrast, has no solution. Faced with a predicament, people can develop responses, but not solutions. Those responses may succeed, they may fail, or they may fall somewhere in between, but no response can erase a predicament. Predicaments have outcomes that can be managed, but circumstances cannot be returned to their original state.

Greer framed this distinction in terms of the enormous changes wrought by the rise of industrialization and English wars of conquest upon a prosperous English farming village in 1700. For many villagers, the transformations of that era were wrenching and fatal. What those English villagers faced in the years after 1700 constituted a predicament, not a problem, because change was inevitable and the consequences were unavoidable.

If you have a problem on your hands, then spending time searching for a solution is a perfectly good use of your resources, because by definition, a solution exists. Seeking solutions to a predicament, on the other hand, is a waste of time because none exist; all you will find are outcomes that must be managed as intelligently as possible. Growing older, depleting a finite resource, and developing Type I diabetes are all examples of predicaments. The historical search for the fountain of youth was a perfect example of an attempt to solve the predicament of aging—a very attractive proposition, if a fountain could ever be found—by treating it as a problem with a potential solution (the fountain). But sadly, those efforts were a complete waste of time.

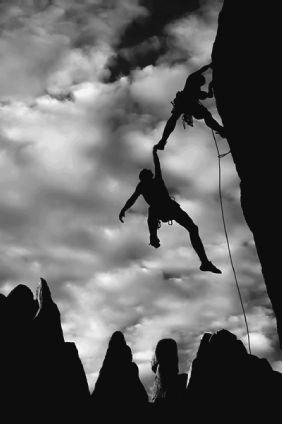

Let us first explore the essence of having a problem. Look at the two gentlemen in

Figure 8.1

. They have a problem on their hands.

I admit that this is an extreme example, as no prudent climbers would ever put themselves in this situation, but it illustrates my point. There are a number of solutions to this problem that would return both climbers to their original condition of relative safety. Perhaps a big mattress could be placed under them, a rope could be lowered, or the climber hanging by a toe could even reach the rock face and climb down all on his own. Any of these solutions could result in both climbers returning to the ground safe and sound. Solutions exist that potentially allow both participants to return to their previous, presumably unimpeded state.

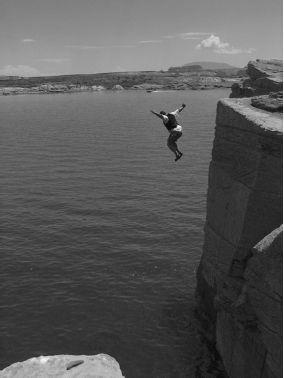

The gentleman in

Figure 8.2

, however, has a predicament on his hands.

No matter how fast or how hard he pinwheels his arms backward, he isn’t going to fly back to the top of the cliff. He is going to get wet; that outcome is certain. And he needs to carefully manage his current situation to secure the safest outcome that he can, by trying to hit the water feet first instead of belly flopping.

What if the gentleman plummeting toward the water spends his time busily thinking of clever ways to fly back to the top of the cliff, instead of focusing on how he will land in the water? First, he won’t succeed, because no feasible solution exists there. Second, he’ll waste time and divert critical mental resources away from the all-important task of managing the best landing possible, and with this approach he will be placing himself at greater risk of injury, or worse. When faced with a predicament, seeking a solution isn’t just a useless thing to do; it is the wrong thing to do. Critical time and resources should be devoted to managing the outcome, not trying to do the impossible.

In this book, we are going to review reams of data collectively pointing to the fact that we’re facing a very large predicament made up of a series of smaller, nested predicaments. The ongoing depletion of energy, the frivolous but deadly serious mountains of debt that we have accumulated, the advancing age of baby boomers, and depleting minerals are just some examples of the predicaments we face.

Yet many people and most politicians spend nearly all of their time treating these predicaments as if they were problems. Solutions are sought, promised, and counted upon where none really exist, because predicaments have been confused with problems. Even as we face dozens of outcomes that are far more dire than a painful belly flop, we find our leadership either gazing elsewhere or promising what can’t be delivered.

By failing to appreciate the nature of our collective predicament, we place ourselves at greater risk, because the longer we dither, less time and fewer options remain. As you read this book, it will be helpful for you to be on the lookout for predicaments and problems, and to recall the important distinction between the two.

CHAPTER 9

What Is Wealth?

(Hint: It’s Not Money)

When Becca and I first decided to move away from our suburban location in Mystic, Connecticut, we drove around southern New Hampshire, Vermont, and central Massachusetts looking for a place to settle. Our list of criteria included typical things such as a nice neighborhood and proximity to culture and shopping, but I had one additional thing on my personal list: good soil. Knowing that I wanted to have a big garden, and knowing that it’s much easier to start with good soil than to build it up from scratch, I had good soil in the “non-negotiable column” on my mental list.

As we drove around, I kept a trained eye on the types of trees and plants in each area, looking for the plant-based clues that would let me know if the soil underneath was good quality or not. I knew that an excess of pine trees often indicate that weak, sandy, and acidic soils are underneath, while maple trees suggest rich, sweet soils.

After passing through a succession of small towns, each established 150 or more years ago, a relationship suddenly became apparent to me. In the towns surrounded by pine trees, the historic churches were small, modest affairs, generally without steeples. The churches looked poor. But in the towns with maple trees, the churches were invariably grander, with large, ornate steeples attached. Small, modest churches in the poorer soil communities; large, ornate churches in the wealthier soil communities. All at once, the saying “dirt poor” took on new meaning to me.

The phrase originally dates from the Great Depression and may well have meant “poor as dirt,” but to me, from that trip on, it could only convey that one is as rich as one’s soil. It must have been axiomatic to our ancestors, whose lives and livelihoods depended on agriculture, that if your dirt was poor, you were poor, too. They knew, in a way that most of us have either forgotten or never learned, that wealth comes from the ground. If two people work just as hard as each other, but one enjoys fine, rich soil and the other struggles with poor dirt, they will reap very different rewards for their efforts. One will be wealthy and the other poor; one is dirt poor and the other is dirt rich. Very simply, all wealth originates with resources from the earth.

We have lost sight of this connection in recent decades because we have been bestowed with the most amazing abundance of magical, wealth-producing stuff ever pulled out of the ground: petroleum. It has masked the previous direct relationship between wealth and land-based resources, which has been a central part of true wealth for every generation except for the most recent ones. It’s unlikely that the nature of this relationship can remain hidden for much longer.

A Hierarchy of Wealth

Let’s begin by describing what we mean by “wealth.” We can think of wealth as coming in three layers, like a pyramid of sorts. At the bottom of the pyramid sits primary wealth, then secondary wealth, and finally tertiary wealth.

Rich soils, concentrated ores, thick seams of coal, gushing oil, fresh water, and abundant fisheries are all examples of

primary wealth

. The foundation of the wealth pyramid comprises these concentrated resources. Today we might call this our “natural resource base,” but once upon a time your access to these things (or lack thereof) meant the physical difference between a life of ease and a life of hardship.

Secondary wealth

is what we make from primary wealth. Ore becomes steel, abundant fisheries lead to dinner on the table, soil becomes food in the store, and trees turn into lumber. The richer, closer, and more concentrated your primary wealth, the easier the task of creating secondary wealth and the more likely you were, in the past, to be wealthy, or rich. If your soil was “dirt poor,” then you had a weak source of primary wealth, and no matter how devotedly or intelligently you worked, you could never achieve the same level of productivity (or wealth) that would be possible if you were working rich soil.

The landed gentry of antiquity were as wealthy as their lands were productive and their holdings expansive. Before the Industrial Revolution (in other words, not all that long ago), this very basic connection was not only well understood, it formed the basis for societal hierarchies. There were wealthy people who owned land, and then there was everybody else. The same is true for weak grades of mineral ores as compared to high grades, or an overharvested fishing ground as compared to a healthy one. Poor primary wealth translates into poor secondary wealth.

We can transform primary wealth into secondary wealth more intelligently, quickly, and cost-effectively with every passing year as we evolve continued improvements in technology and processes. But no matter how good we get at making these transformations, there can be no secondary wealth unless there is primary wealth to begin with. Unless there are trees to mill, there’s no lumber; no oil means no gas; without ores we can’t refine new metals; and plants will not grow if they don’t have the nutrients and water they need. Without primary wealth there cannot be secondary wealth. The second depends on the first; it’s a requirement.

The final layer,

tertiary wealth

, consists of all of the paper abstractions that we layer upon the first two sources of wealth. Derivatives, stocks, bonds, and every other paper vehicle you can think of comprise forms of tertiary wealth. Such “wealth” is a claim on the other two forms, but it is not wealth itself. If you grow wheat, you can always eat it if circumstances require, but good luck obtaining any sustenance from your (paper or electronic) wheat futures contracts. To repeat, third-order wealth is a

claim

on sources of wealth, and not a

source

of wealth itself. The distinction is vital.

Without the prior two forms of wealth, third-order wealth has no value and no meaning at all. For example, imagine that we hold stock in a mining company. One day the stock has lots of value, perhaps billions of dollars’ worth. But if the next day the mine collapses, dragging the refinery and all of the capital stock of the entire company down into its hole, which then irrevocably floods. Our stock shares in the mining company—our tertiary claims on that mining wealth—become totally worthless. The reason for this is simple: The earth is the source of primary wealth. The long chain from primary wealth to tertiary wealth begins with the abundance of the earth and ends with some impressively complicated paper-based abstractions that even the brightest Wall Street minds sometimes have trouble deciphering.

As you read this book, it will be helpful to recall that what most people call “wealth” isn’t actually an independent

source

of wealth, but is instead a dependent

claim

on wealth. In a world of limitless natural resources (primary wealth), the distinction between independent and dependent wealth is irrelevant. We can ignore it, concentrating instead on playing the game of accumulating as much wealth of all kinds as we can while it’s our turn to be in our prime. But in a world of

limited

resources—soon to be

limiting

resources—the distinction is vital, especially when the claims on that wealth are literally manufactured out of thin air.

For many of us, tertiary wealth is all that we know; it seems very real, and we base many of our future expectations and dreams on how much of it we hold. Stocks and bonds have been tangible, useful vehicles for storing and growing our collective wealth for such a long period of time that it’s easy to see why they’ve assumed such a superior position in most people’s minds.

It bears repeating, however, that all wealth begins with primary wealth; without it, there is nothing. Today, when there is more abundant luxury available to more people than at any point in history, much of it traveling from very far away to arrive in our lives as if by magic, it has been easy to lose sight of this fact, but it remains as true today as ever before.

Money and Wealth

What about money—how does it factor into the wealth story? Money can and should be a store of wealth, but it’s not wealth itself. It’s a way for us to conveniently measure and transfer ownership of true wealth from one entity to another, but just like a stock, bond, derivative, or any other financial product, money is simply a claim on wealth. It also happens to be an exceedingly important social contract that we collectively uphold, a vehicle in which we’ve invested the enormous power to shape lives, nations, and destinies. Ultimately, though, what we call “money” is either a piece of paper (indistinct from any other except for the ink patterns on it) or it’s an ephemeral collection of numbers that exist as a series of ones and zeros on a computer hard drive somewhere.

Money has value because, and only because, we collectively agree that it can be exchanged for something. If we go far enough backward or forward in any line of transactions, that “something” is always some form of primary or secondary wealth. Perhaps we exchange money for a college education; this might seem to be quite different and less tangible than the examples of primary or secondary wealth that I’ve already described. But if we keep following the path of money in that exchange, we’ll eventually find the money in the pocket of a college professor who will use it to buy food, or clothing, or a house, or some other form of primary or secondary wealth.

The point of money is to help us secure those things that we need, beginning at the very bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

1

We start with food, shelter, warmth, and security, and then progress higher if and only if the base needs have first been satisfied. It’s vitally important, then, that money be stable and trustworthy, because if it’s not, and people begin to suspect that money might fail to enable them to meet their basic needs, the entire social contract that money fulfills will begin to fray. As long as money exists in a balance with actual primary and secondary

sources

of wealth, then it will retain its perceived value and perform an important function. However, when the supply of money gets out of balance with resources, money’s value can begin to gyrate wildly. We call this process

inflation

or

deflation

, depending on whether the gyration goes down or up.

The Nature of Wealth

The idea that monetary wealth originates with the wealth of the earth is hardly new, but abundant primary wealth, as described here, has been such an assured feature of the landscape of the last few centuries that it seems to be almost entirely taken for granted. Over two hundred years ago, the great economic thinker and observer Adam Smith took great pains to describe how wealth came about, but given that he lived during a time of natural primary abundance and poorly formed tertiary paper-based wealth abstractions, he focused mainly on the role of labor in creating wealth. He turned his considerable attention to secondary wealth and did a most credible job of isolating the essential features by which better-organized labor led to greater wealth. Here he essentially discounts the importance of “soil, climate, and territory” compared to the number of people laboring productively:

[T]his proportion [between production and consumption] must in every nation be regulated by two different circumstances; first by the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which its labour is generally applied; and, secondly, by the proportion between the number of those who are employed in useful labour, and that of those who are not so employed. Whatever be the soil, climate, or extent of territory of any particular nation, the abundance or scantiness of its annual supply must, in that particular situation, depend upon those two circumstances.

1

This was a fair view of wealth in the late eighteenth century. Given the limitless natural abundance of the time, those who could transform primary into secondary wealth faster and more productively created wealth the quickest.

We live under very different circumstances than Smith, but the question of how we create wealth remains as relevant today as it was in his day. There are thousands of books to help you navigate tertiary wealth, virtually all of them assuming that the future will resemble the present, only bigger. But here we take a very different stance, recalling that all wealth starts from the bottom of the wealth pyramid with primary wealth and observing that the creation of secondary wealth, without exception, requires energy, which seems the least likely candidate to continue its exponential trend of the past 300 years for very much longer.

By swiveling our gaze to a long-forgotten and dusty intellectual realm, we have the chance to rediscover some basic truths and stake out our positions in relative quiet before the masses arrive like so many wild-eyed land-rush speculators bent on grabbing their share while they still can. The basic truth is this: Our money, debts, stocks, and bonds have a high value in a world of constant economic growth—and a much, much lower value in a world without economic growth. Constant economic growth requires constant inputs of primary resources, especially energy, and someday those will undoubtedly fail to expand any further.