The Grand Alliance (70 page)

Read The Grand Alliance Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II

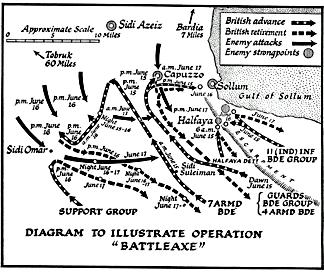

At this decisive moment General Wavell flew to General Beresford-Peirse’s battle headquarters. He still hoped to turn the scale by Creagh’s armoured attack. He got into his airplane and flew to the 7th Armoured Division. He had no sooner reached it than he learned that General Messervy had independently decided that with the double threat against his flank and rear, which he now estimated as at least two hundred tanks, he must immediately retreat to avoid being surrounded. He had given orders accordingly.

Wavell, out on the desert flank with Creagh, was confronted with this fact and concurred in the decision. Our stroke had failed. The withdrawal of the whole force was carried out in good order, protected by our fighter aircraft. The enemy did not press the pursuit, partly no doubt because his armour The Grand Alliance

427

was heavily attacked by R.A.F. bombers. There was probably, however, another reason. As we now know, Rommel’s orders were to act purely on the defensive and to build up resources for operations in the autumn. To have embroiled himself in a strong pursuit across the frontier, and suffered losses thereby, would have been in direct contravention of orders.

The policy of close protection of our troops by fighter aircraft, though effective, led to dispersion and a relatively high rate of air casualties. When, on the second day, the enemy air effort intensified, it was decided to modify the policy and, while continuing a degree of protection, to operate offensively in large units and farther afield. When the withdrawal began, on the seventeenth, our fighters not only fended off three out of four considerable air attacks on our troops, but also co-operated with the bombers, often at low level, against enemy columns. These attacks undoubtedly impeded the enemy’s movement and inflicted considerable casualties. Our airmen rendered good service to the withdrawing troops, but they were hampered by the difficulty of distinguishing between our own and enemy forces.

Our casualties in the three days’ battle were just over one thousand, of which a hundred and fifty were killed and two hundred and fifty missing. Twenty-nine cruisers and fifty-eight “I” tanks were lost, the cruisers mainly from enemy action. A considerable portion of the losses in “I” tanks were due to mechanical breakdowns, there being no transporters to bring them back. The best part of one hundred enemy tanks were claimed as accounted for; five hundred and seventy prisoners were taken and many enemy corpses buried.

The Grand Alliance

428

Although this action may seem small compared with the scale of the Mediterranean war in all its various campaigns, its failure was to me a most bitter blow. Success in the Desert would have meant the destruction of Rommel’s audacious force. Tobruk would have been relieved, and the enemy’s retreat might well have carried him back beyond Benghazi as fast as he had come. It was for this supreme object, as I judged it, that all the perils of “Tiger” had been dared. No news had reached me of the events of the seventeenth, and, knowing that the result must soon come in, I went down to Chartwell, which was all shut up, wishing

The Grand Alliance

429

to be alone. Here I got the reports of what had happened. I wandered about the valley disconsolately for some hours.

The reader who has followed the exchange of telegrams between General Wavell and me and with the Chiefs of Staff will be prepared in his mind for the decision which I took in the last ten days of June, 1941. At home we had the feeling that Wavell was a tired man. It might well be said that we had ridden the willing horse to a standstill. The extraordinary convergence of five or six different theatres, with their ups and downs, especially downs, upon a single Commander-in-Chief constituted a strain to which few soldiers have been subjected. I was discontented with Wavell’s provision for the defence of Crete, and especially that a few more tanks had not been sent. The Chiefs of Staff had overruled him in favour of the small but most fortunate plunge into Iraq which had resulted in the relief of Habbaniya and complete local success. One of their telegrams had provoked from him an offer of resignation which was not pressed, but which I did not refuse. Finally, there was “Battleaxe,” which Wavell had undertaken in loyalty to the risks I had successfully run in sending out the Tiger Cubs. I was dissatisfied with the arrangements made by the Middle East Headquarters Staff for the reception of the Tiger Cubs, carried to his aid through the deadly Mediterranean at so much hazard and with so much luck. I admired the spirit with which he had fought this small battle, which might have been so important, and his extreme disregard of all personal risks in flying to and fro on the wide, confused field of fighting. But, as has been described, the operation seemed ill-concerted, especially from the failure to make a sortie from the Tobruk sallyport as an indispensable preliminary and concomitant.

The Grand Alliance

430

Above all this there hung the fact of the beating-in of the desert flank by Rommel, which had undermined and overthrown all the Greek projects on which we had embarked, with all their sullen dangers and glittering prizes in what was for us the supreme sphere of the Balkan War.

General Ismay, who was so close to me every day, has recorded the following: “All of us at the centre, including Wavell’s particular friends and advisers, got the impression that he had been tremendously affected by the breach of his desert flank. His Intelligence had been at fault, and the sudden pounce came as a complete surprise. I seem to remember Eden saying that Wavell had ‘aged ten years in the night.’ ”I am reminded of having commented: “Rommel has torn the new-won laurels from Wavell’s brow and thrown them in the sand.” This was not a true thought, but only a passing pang. Judgment upon all this can only be made in relation to the authentic documents written at the time which this volume contains, and no doubt also upon much other valuable evidence which time will disclose. The fact remains that after “Battleaxe” I came to the conclusion that there should be a change.

General Auchinleck was now Commander-in-Chief in India.

I had not altogether liked his attitude in the Norwegian campaign at Narvik. He had seemed to be inclined to play too much for safety and certainty, neither of which exists in war, and to be content to subordinate everything to the satisfaction of what he estimated as minimum requirements. However, I had been much impressed with his personal qualities, his presence and high character.

When after Narvik he had taken over the Southern Command I received from many quarters, official and private, testimony to the vigour and structure which he had given to that important region. His appointment as Commander-in-Chief in India had been generally The Grand Alliance

431

acclaimed. We have seen how forthcoming he had been about sending the Indian forces to Basra, and the ardour with which he had addressed himself to the suppression of the revolt in Iraq. I had the conviction that in Auchinleck I should bring a new, fresh figure to bear the multiple strains of the Middle East, and that Wavell, on the other hand, would find in the great Indian command time to regain his strength before the new but impending challenges and opportunities arrived. I found that these views of mine encountered no resistance in our Ministerial and military circles in London. The reader must not forget that I never wielded autocratic powers, and always had to move with and focus political and professional opinion. Accordingly I sent the following telegrams:

Prime

Minister

to

21 June 41

General Wavell

I have come to the conclusion that the public interest

will best be served by the appointment of General

Auchinleck to relieve you in the command of the armies

of the Middle East. I have greatly admired your command and conduct of these armies both in success and

adversity, and the victories which are associated with

your name will be famous in the story of the British

Army, and are an important contribution to our final

success in this obstinate war. I feel, however, that after

the long strain you have borne a new eye and a new

hand are required in this most seriously menaced

theatre. I am sure that you are incomparably the best

man and most distinguished officer to fill the vacancy of

Commander-in-Chief in India. I have consulted the

Viceroy upon the subject, and he assures me that your

assumption of this great office and task will be warmly

welcomed in India, and adds that he himself will be

proud to work with one who bears, in his own words,

“so shining a record.” I propose, therefore, to submit

your name to His Majesty accordingly.

The Grand Alliance

432

2. General Auchinleck is being ordered to proceed

at once to Cairo, where you will make him acquainted

with the whole situation and concert with him the future

measures which you and he will take in common to

meet the German drive to the East now clearly impending. I trust he may arrive by air within the next four or

five days at latest. After you have settled everything up

with him you should proceed at your earliest convenience to India. No announcement will be made, and

the matter must be kept strictly secret until you are both

at your posts.

Prime

Minister

to

21 June 41

Viceroy of India

Will you kindly convey the following to General

Auchinleck. I have already telegraphed to General

Wavell.

After very careful consideration of all the circumstances I have decided to submit your name to the King

for the command of His Majesty’s armies in the Middle

East. You should proceed forthwith to Cairo and relieve

General Wavell. General Wavell will succeed you as

Commander-in-Chief in India. You should confer with

him upon the whole situation, and should also concert

with him the measures you will take in common to

arrest the eastward movement of the German armies

which is clearly impending. Pray let me know when you

will arrive. The change is to be kept absolutely secret

until you are installed in your new post.

Wavell received the decision with poise and dignity. He was at that time about to undertake a flight to Abyssinia which proved extremely dangerous. His biographer records that on reading my message he said, “The Prime Minister is quite right. There ought to be a new eye and a new hand in this theatre.” In regard to the new command, he placed himself entirely at the disposal of His Majesty’s Government.