The Other Slavery (28 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Before the arrival of Europeans, such interactions had been common. In the period between 1450 and 1600, Pueblo Indians had enjoyed close trading relationships with outlying nomads. In spite of their

strikingly different lifestyles, town dwellers and nomads complemented each other well. The Pueblos exchanged corn and ceramics with hunter-gatherers for bison meat and hides: carbohydrates for protein, and pottery for hides. The Spaniards’ arrival in 1598 severely reduced this trade. The Pueblos now had to surrender their agricultural surplus to encomenderos and missionaries and therefore retained few, if any, items to exchange. The archaeological record shows fewer bison bones and bison-related objects among the Pueblos during the seventeenth century. Additionally, the Spaniards launched raids against outlying hunter-gatherers, further disrupting Pueblo-Plains trading networks. With the Spanish exodus in 1680, the Pueblos had a chance to reestablish their old ties with the nomads. This trade appears to have been reinvigorated in a very short time.

4

Not only were Plains Indians more present in the pueblos of New Mexico, but they were also far more assertive. Horses had ushered in a revolution in the region. As historian Pekka Hämäläinen ably puts it, equestrian Indians did everything better than their counterparts who traveled by foot—move, hunt, trade, and wage war. Equestrian Indians could even challenge the Spaniards. The horse revolution unfolded by fits and starts during the 1600s, speeding up considerably with the Pueblo Revolt. When Spanish colonists hastily abandoned New Mexico in the summer of 1680, they left behind the largest herd of horses anywhere in northern Mexico. The Pueblo Indians lost little time in appropriating these animals and trading them away. The Apaches, Navajos, Utes, and others thus gained strength during the tumultuous final dec-ades of the seventeenth century.

5

Spanish officials were forced to tolerate the Pueblo-Plains ties and to keep vigilant in case of an all-Indian alliance against them. Such a scenario was not far-fetched. In 1704–1705 New Mexican governor Juan Páez Hurtado conducted a full-scale “investigation into the friendship between the Pueblos and the surrounding heathens” after learning that some Indians in the pueblo of San Juan had brokered a peace agreement with the Navajos, Utes, various bands of Apaches (Jicarilla, Trementina, Acho, Faraon, and Gila), and other pueblos. It looked like a formidable cabal that could easily lead to a general insurrection. Governor Páez

Hurtado’s vigorous investigation prevented such an outcome, but the episode is significant because it illustrates how Apaches, Navajos, Utes, and other outlying Indians learned to use their newfound ties with the Pueblos to put pressure on the Spaniards—and to extract commercial privileges.

6

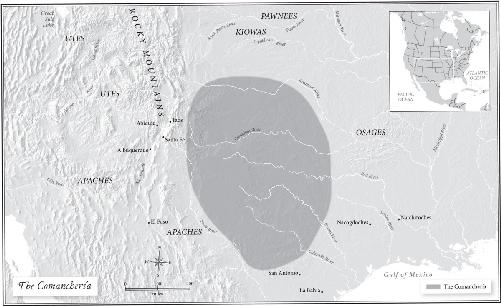

The case of the Comanches reveals how thoroughly the adoption of horses could change a group of peripatetic Indians. The Comanches were newcomers to the region. Only in the final decades of the seventeenth century did they start to move south toward New Mexico or to begin experimenting with horses, which they probably first obtained from the Utes, their linguistic cousins. No Spaniard had ever heard of the Comanches until the early years of the eighteenth century. They and the Utes shared a homeland somewhere north of the Pueblo world, possibly in the eastern Colorado Plateau, and together they muscled their way into the trading fairs held in New Mexico. The Spaniards and Pueblos soon became wary of these two stalwart equestrian peoples. Rumors swirled that the Comanches and Utes were mounted barbarians descending on New Mexico in order to pillage. But these nomads also brought valuable trade items, including tanned bison hides, bison meat, and Indian captives.

7

Comanche captive taking introduced Apaches from the east, Navajos from the west, and Pawnees from the north into New Mexico. The Comanches’ radius of action was astonishing. In 1731 a New Mexican friar asked one of the Comanches’ captives to which nation he belonged and how far it was to his country of origin. The slave responded that he was a “Ponna” (quite possibly a Pawnee, whose traditional homeland was along the North Platte and Loup Rivers in present-day Nebraska). The Indian also said that he had traveled with his captors for “one hundred suns,” moving at a rate of about ten leagues (thirty miles) for each one. The friar estimated that in the course of a year, Comanches might travel “more than one thousand leagues [three thousand miles] from New Mexico,” a distance that may have been entirely possible, considering that Pawnee country was eight hundred miles away from northern New Mexico and that the Comanches traveled to and from these lands, making various detours along the way.

8

The Comanches sold their first slaves in New Mexico sometime in the first decade of the eighteenth century. By the 1720s, they had become well-established traders. And by the 1760s, they were acknowledged as the preeminent suppliers of captives in the region. Their visits to New Mexico became signal events in the yearly calendar that mobilized the entire province. In 1761 a New Mexican friar wrote to the viceroy of Mexico:

Here the governor, alcaldes, and lieutenants gather together as many horses as they can; here is collected all the ironware possible, such as axes, hoes, wedges, picks, bridles, machetes,

belduques

[heavy knives used in the hide trade], and knives; here in short is gathered everything possible for trade and barter with these barbarians in exchange for deer and buffalo hides, and what is saddest, in exchange for Indian slaves, men and women, small and large, a great multitude of both sexes, for they are gold and silver and the richest treasure for the governors who gorge themselves first with the largest mouthfuls from this table, while the rest eat the crumbs.

9

It is easy to miss the full implications of this traffic of captives. In the seventeenth century, Spanish cavalrymen had attacked the nomadic groups in New Mexico practically at will. One after another, the Spanish governors had ordered slaving raids on the Apaches, Navajos, and other hunter-gatherers, peoples who still possessed very few horses. But while the Spaniards initially held the upper hand, the diffusion of horses evened out the playing field.

10

After the Spanish retreat following the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, nomadic Indian traders with newfound access to horses began to muscle their way into the markets of New Mexico. In 1694, barely two years after the Spaniards had retaken control of the province, a group of Navajos arrived with the intention of selling Pawnee children. The Spanish authorities initially refused to acquire the young captives—after all, as the

Recopilación de las leyes de Indias

had made clear fourteen years earlier, Indian slavery was illegal in all circumstances, even when slaves were being ransomed from other Indians. Their refusal may also have had something to do with the desire of some New Mexican traders to

monopolize the traffic of slaves. But the spurned Navajos did not give up easily. To ratchet up the pressure, the traffickers proceeded to behead the captive children within the Spanish colonists’ sight. In the short term, the Utes lost their “merchandise.” But in the longer term, the stratagem prompted New Mexican officials to reconsider the ban against “ransoming” Indian captives.

11

Some years later, in 1704–1705, the Navajos, together with other nomads and Pueblo Indians, increased the pressure even more by threatening an all-out anti-Spanish revolt. Interestingly, it was around this time that New Mexican officials began sanctioning the ransoming of Indian captives sold by these groups. In effect, the Navajos, Utes, Comanches, and Apaches forced New Mexican authorities to break the law and accept their captives. Willingly or not, New Mexicans had become their market.

12

By the middle of the eighteenth century, these commercial and diplomatic relations had become normalized. In 1752 Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín reached peace agreements with the Comanches and Utes. Governor Cachupín understood quite well that the best way to achieve a lasting peace with these equestrian powers was by maintaining open trade relations with them and fostering mutual dependence. Thus New Mexico’s annual trading fairs became choreographed events in the service of diplomacy. Indeed, Governor Cachupín left to his successor a set of revealing instructions: “It is necessary, when the Comanches come to Taos to trade, that Your Grace present yourself in that pueblo surrounded with a suitable guard and your person adorned with all splendor possible.” The governor also urged his successor to show Comanches “every kindness and affection,” sitting down with them to smoke tobacco, posting soldiers to relieve them of the responsibility of looking after their horses (something “they appreciate in the highest degree”), leaving them “unmolested in their selling,” and making sure that “any appeal for justice is met at once,” because “they are always attentive to the governor’s actions and decisions from which they draw inferences.” According to Governor Cachupín, “The conservation of the friendship of this Ute nation and the rest of its allied tribes is of the greatest consideration because of the favorable results which their trade and good

relations bring to this province,” and he urged a policy of commercial access that included the selling of Indian captives.

13

The Comanches flooded the New Mexican market with captives. In the previous century, New Mexicans had kept slaves in their own houses and ranches, and shipped any surplus out to Parral and other mining centers and cities in the south. The New Mexico–Chihuahua trade had functioned as a safety valve, guarding against an oversupply of slaves in New Mexico. Now the Comanches, Apaches, Utes, and others stepped up their selling of captives in New Mexico at the same time the silver mines of Chihuahua were absorbing fewer slaves than before. New Mexico’s servile population grew and could no longer be contained in Spanish households and ranches. The clearest symptom was the emergence of new settlements consisting of former slaves. As Friar Miguel de Menchero explained, “Sometimes it happens that the Indians are not well treated in this servitude, no thought being given to the hardships of their captivity . . . and for this reason they desert and become apostates.” Many servants escaped, banded together, and mustered the courage to ask for recognition and even request land in outlying areas to start new communities. Such Indians became known as

genízaros,

a term that conjures thoughts of captivity, servitude, and the merging of Plains, Pueblo, and Hispanic cultural traits. In 1733 a group of one hundred Indians who identified themselves as

“los genízaros”

wrote to the governor of New Mexico claiming that they were no longer in servitude to any Spaniard and therefore wished to obtain some land. This first list of genízaros reveals the geography of enslavement at the time, as many of the signatories were Indians from the plains, including Pawnees, Jumanos, Apaches, and Kiowas. Friar Menchero visited a genízaro community south of Albuquerque in 1744. This crude community called Tomé consisted entirely of “nations that had been taken captive by the Comanche Apaches.” In the 1750s and 1760s, more genízaro settlements came into existence, an indication of the slaving prowess of the Comanches and other providers.

14

Indian captivity not only transformed New Mexico but also refashioned the Comanches and their principal victims. The quest for loot caused the Comanches to leave the tablelands and mountains of the

Colorado Plateau and move to the plains. In the 1720s, merely one generation after having acquired horses, these mounted Indians abruptly shifted their base of operations to the east. They descended onto the immense grasslands, with their rolling hills and abundant herds of bison. But more than the bison, what initially attracted the Comanches to the plains were the isolated Apache villages.

15

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Apaches led a nomadic existence on these plains. They did not have horses, so they moved from camp to camp on foot and with the help of dogs pulling travois. In the late seventeenth century, however, the Apaches began to settle down. Once again, the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 was a major catalyst for this change. The rebellion and subsequent reconquest by the Spaniards impelled many Pueblo Indians to flee New Mexico and join these outlying bands. In 1696, fearing reprisals from the returning Spaniards, the Pueblos of Picurís loaded their horses, gathered their goats, and left for the lands of their longtime Apache trading partners. The Apaches already practiced limited forms of agriculture, but the Pueblo refugees introduced new agricultural methods that enabled the Apaches to remain in place all year round. In the fifty-year period between 1675 and 1725—the blink of an eye in archaeological terms—dozens of Apache settlements sprouted up along the streams, lakes, and ponds of the large region between the Rocky Mountains and the 100th meridian, spanning much of modern-day Kansas and Nebraska. In 1706 a group of Spanish soldiers visited one of these mixed communities of Apaches and Pueblos by the Arkansas River named El Cuartelejo. The residents lived in spacious adobe huts and cultivated small plots of corn, kidney beans, pumpkins, and watermelons, in addition to hunting bison.

16