The Other Slavery (29 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

What began as a series of Comanche raiding excursions on these exposed settlements rapidly evolved into a full-fledged plan of colonization. Archival records contain only faint traces of the life-and-death battles that raged between Comanches and Apaches during the first half of the eighteenth century. The invaders’ greatest strategic advantage was their ability to choose when and where to strike. They operated as unified squadrons pitted against scattered settlements. One Spaniard marveled that even though the Comanches were “the most barbarous nation

known, nonetheless they conserve such solidarity both on the marches that they continually undertake, wandering like Israelites, as well as in the camps that they establish where they settle.” This was a crucial advantage, but the Plains Apaches, who had also acquired horses by the early eighteenth century, were quite capable of defending themselves. The clashes were sometimes ferocious. Around 1724 they fought a battle at an otherwise unidentified place referred to as “the Great Mountain of Iron,” which lasted for nine days. Sixty years later, a Spanish official remembered this encounter as a milestone in the all-out war between the two foes.

17

In the end, the Comanches prevailed, employing captivity as a primary tool to remake the region. They raided Apache settlements, burning houses and fields, probably deliberately adopting a scorched-earth strategy to permanently dislodge their antagonists. To avoid complications, they generally killed the adult males on the spot, then seized the women and children. In 1719 some Jicarilla Apaches recounted to the governor of New Mexico how “they were very sad and discouraged because of the repeated attacks which their enemies, the Utes and Comanches, make upon them. They had killed many of their nation and carried off their women and children captives until they now no longer knew where to go to live in safety.” Five years later, a group of Carlana Apaches could well have been describing the same incident: “The Comanche nation, their enemies, had attacked them with a large number in their rancherías in such a manner that they could not make use of weapons for their defense. They launched themselves with such daring and resolution that they killed many men, carrying off their women and children as captives.”

18

The Comanches took many of their captives to New Mexico, where they exchanged them for horses and knives. In the absence of money or silver, women and children constituted a versatile medium of exchange accepted by Spaniards, Frenchmen, Englishmen, Pueblos, and many other Indian groups of the region. But the Comanches also kept some of the victims. Other North American Indians, including the Iroquois and Cherokees, had long raided neighboring groups to avenge or replace deceased relatives. These so-called “mourning wars” could

sometimes escalate into all-out conflicts. It is possible that the Comanches and Apaches understood their conflict at least partly in these terms.

19

Comanche males competed with one another by expanding their kinship networks. The Comanches practiced polygyny, so raids allowed men to acquire additional wives. Successful males could have three, four, five, or up to ten or more wives. Their “main instinct,” commented New Mexican governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín in 1750, “was to have an abundance of women, stealing them from other nations to increase their own.” This was not just about prestige, sexual gratification, and reproduction. In an equestrian society, women provided specialized labor. For instance, a skilled male hunter could bring down several bison in just one hour. But once the exhilaration of the chase was over, hunters faced the daunting task of processing dead animals spread over great distances. Each carcass could weigh a ton or more. Flaying open a bison, cutting the choice meat from the back and around the ribs, removing the inner organs, cleaning the hide, and severing the legs and head required not just skill but above all untold amounts of labor. Captive women spent endless hours stooping over these large carcasses, withstanding the heat, stench, and exhaustion involved in preparing the hides for their many uses; looking after the horses; and doing the myriad chores of life in an encampment and on the move. Circumstances could vary, but enslaved women usually began at the bottom of the hierarchy of wives and were given the most taxing and unpleasant tasks. They were subordinate not only to their Comanche husbands but also to the “first wives,” who tended to be Comanche by birth and who managed the labor of the lower-ranking women on a daily basis.

20

Captive children faced different circumstances. Older boys, because they could not readily identify with their captors and had difficulty learning the language, were frequently excluded from the Comanche kinship system. These unlucky captives sometimes remained slaves for life. In contrast, younger captives were often adopted into a family and regarded as full-fledged members of it. Comanches showed a marked preference for boys over girls. Anthropologist Joaquín Rivaya-Martínez has assembled a database of more than fourteen hundred Comanche captives in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. More than seventy

percent of the children in his sample are boys. They were in high demand primarily because of the relative scarcity of males in Comanche society. Constant battles and raids took a heavy toll on the male population. Reportedly, relatively few Comanche warriors reached old age. The marked preference for boys may also have been a result of the growing number of horses the Comanches came to control. Breaking horses and looking after them became major occupations in Comanche society, and boys were deemed more appropriate for such tasks than girls. At the height of their power in the nineteenth century, the Comanches owned so many horses that each boy was responsible for a herd of as many as 150 animals, according to one witness. Looking after the horses was the first task assigned to these young captives; it was a way of testing their loyalty to the group. The boys also had to recognize their captors as their parents, learn the ways of the society, and earn sufficient trust to receive more difficult assignments. In the fullness of time, they were allowed to take part in bison hunts and eventually were invited to accompany the warriors in raids against other Indians, including their former kinsmen.

21

Indian captivity was at the heart of the transformation of the plains. The Comanches obliterated Apache settlements across an enormous area, carrying off and selling some Apaches in New Mexico, taking Apache women as their secondary wives, and enslaving and adopting Apache children before unleashing them on their former people. In short, the Apachería became the Comanchería largely through captivity. By the 1760s, the Comanches had forged a stable homeland to the east of the kingdom of New Mexico. Stretching from the Arkansas River in the north to the Balcones Escarpment in the south, and from the eastern flank of New Mexico all the way to Spanish Texas, the Comanchería was a forbidding region that non-Comanches entered at their own peril. Fifteen thousand Comanches or more occupied this territory, easily exceeding the number of Spaniards or Frenchmen living in what is now the Southwest. The Comanches became the second most numerous indigenous people after the Pueblos of New Mexico. They also surpassed New Mexico in the number of horses they possessed. Because the Comanches measured their wealth in terms of horses, each ranchería could

have hundreds of them. In a profound sense, the Comanches became “the horse people,” breeding them, raiding them, and using them widely as an article of trade.

22

Above all, the Comanchería was better connected than New Mexico to the surrounding Indian and non-Indian peoples. Using bison hides, horses, and slaves as their preferred items of exchange, the Comanches turned their homeland into a trading center. On their western flank, they retained New Mexico as a convenient entrepôt, continuing their yearly embassies to the trading fairs. At the same time, they developed a brisk trade with French Louisiana to the east and with the English to the northeast. Although the Comanches sometimes dealt directly with French and English merchants, these transactions, which could span all of North America, were more commonly mediated by other Indians. In the 1720s and 1730s, Apache captives flowed to places as far away as Quebec, where they came to comprise as many as one-quarter of all Indian slaves of known origin in New France. In return, the Comanches and their allies procured European weapons. During their assault on the San Sabá mission in 1758, for instance, they reportedly carried more than one thousand French muskets—more firearms than were available in all of Spanish Texas.

23

Scholars of slavery in the ancient Mediterranean and Africa have sometimes distinguished between “societies with slaves,” in which slaves were present but did not constitute a majority of the population and were not central to the production of goods, and “slave societies,” which were fundamentally dependent on enslaved peoples. At the height of the African slave trade in the eighteenth century, the proportion of African slaves on some Caribbean islands—including Haiti, Jamaica, and Barbados—reached ninety percent. By this traditional yardstick, the Comanches were merely a “society with slaves.” The ratio of slaves among the Comanches in the nineteenth century may have ranged between ten and twenty-five percent, according to one tentative estimate. And yet this percentage fails to convey the multiple ways in which slavery gave the Comanches the means to acquire horses and weapons and to use these as powerful levers to forge alliances, seek compliance, punish enemies, and secure their borders. In

tangible ways, the Comanchería became a trading center with commercial networks that included many surrounding Indian nations and stretched into the Spanish, French, and British empires.

24

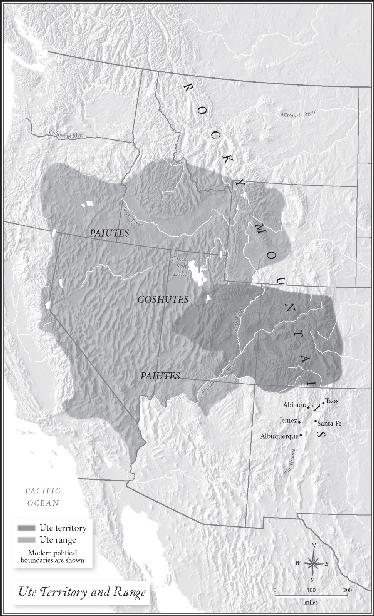

Although the Comanches became preeminent suppliers of captives on the northern fringes of the Spanish empire, they were not alone. The Utes followed a somewhat different trajectory, but they too became active participants in the exchange of captives. The Utes were the ones who possibly gave the Comanches their first horses. They also brought the Comanches into New Mexico as their junior partners. As we have seen, in the early decades of the eighteenth century, these two equestrian peoples shared a range somewhere to the north of the Pueblo world, trading and plundering together.

25

But then their relationship soured. In the 1730s, they began having difficulties, and by midcentury they were engaged in open conflict. As the division deepened, their paths diverged. The Comanches descended onto the plains, dislodged the Apaches, and established a new homeland there. Most Ute bands remained up in the mountains and retained their traditional seasonal migration. In the fall and winter, they remained to the west and north of New Mexico, trading in Taos, Jemez, and other pueblos. New Mexico’s most northwesterly settlement, Abiquiu, became a regular trading stop for many Utes. In the eighteenth century, Abiquiu was a remote village of genízaros that served as a jumping-off point for the Great Basin. Many Utes overwintered in protected areas not too far from this and other outlying settlements. In the spring, they rode west and north, venturing into the Great Basin and visiting portions of what are now Utah, Nevada, and Arizona, even traveling as far as Wyoming, Idaho, and eastern California and Oregon.

26

As they moved away from New Mexico, these Utes encountered an array of indigenous groups, all of whom spoke Numic languages and were more or less related to one another. Immediately to the west of the Colorado Plateau, the Utes entered a transitional region inhabited by smaller bands that possessed fewer horses and practiced small-scale farming. They occasionally intermarried with these Indians—known indistinctly as Utes or Paiutes in the historical record—but did not

treat them quite the same as their own people. As they pushed deeper into the Great Basin, they found peoples to whom they were even more distantly related.

27

The Great Basin is a low-lying area of around two hundred thousand square miles, an enormous sink wedged between the Wasatch Mountains to the east and the Sierra Nevada to the west. A large depression covered in the last ice age by an inland sea called Lake Lahontan, it is now a stark landscape of dried lakebeds, burnt sienna mountains, bleached deserts, and open spaces. The Paiute Indians occupied much of this area, adapting to its challenging environment. They lived in small groups of closely related family members: husband, wife (occasionally more than one), children, and perhaps a few uncles, aunts, grandparents, and cousins. These camps consisted of as few as ten people and seldom exceeded fifty. Atomization was a necessity, given the scarcity of food. These small bands moved from one campsite to another in carefully planned circuits to procure grasses, pine nuts, and other food resources that were available in different locales at different times of year. Although the Great Basin is generally low, its mountains and hills gave these bands access to various ecological niches at different altitudes. When disaster struck, their atomized social organization enabled them to share their resources with one another. For instance, in cases of drought, frost, insect infestation, or some other environmental calamity, one band could request permission to drink water or eat grasses or roots belonging to a neighboring band without jeopardizing all of the groups’ livelihoods. It appears that such requests were usually granted and created bonds of reciprocity.

28