The Other Slavery (27 page)

Authors: Andrés Reséndez

Most threatening of all was the missionaries’ capacity to torture and kill in the name of God. The worst offender was the aptly named Salvador de Guerra, a friar who terrorized the Hopi pueblos during the 1650s. Like other friars working in near-complete isolation, he lived with a concubine in spite of his vows of celibacy. He also forced the Indians to weave cotton

mantas,

setting minimum quotas they had to meet to avoid punishment. And when it came to fighting the Devil, Friar Guerra had few peers. Not only did he beat suspected idolaters and hechiceros,

but he also soaked them with turpentine and set them on fire. In one instance, a witness reported, a luckless Native who survived the turpentine treatment “got up, and desiring to go by a certain road where there is a tank of water to throw himself into it, took another road which leads to Santa Fe, and Fray Salvador de Guerra mounted a horse, thinking that the Indian was going to complain to the government, and followed him, and rode over him with the horse until he killed him.”

31

There is no question that the religious thesis of the Pueblo Revolt explains a great deal. But, like all historical explanations, it hinges on highlighting certain episodes and personalities while de-emphasizing others. The religious character of the movement is so striking and seductive that it overshadows the material motivations of the uprising, which often appear as mere “catalysts” or “triggers” subordinated to the more fundamental religious cleavage.

Especially in the past decade, the research on Indian slavery/servitude has opened new vistas on the turning points of the Pueblo Revolt. New understanding of rising levels of exploitation and enslavement as New Mexico became integrated into the silver economy of northern Mexico—a story told earlier in this book—indicates that it was this pressure, rather than a burst of inquisitorial activity, that led to the growing turmoil in the years leading up to 1680. Surely factors other than “the other slavery” were

causes of the rebellion: long-simmering religious animosities, famine, and illness made the mix even more volatile. But rising levels of exploitation, which can be documented in the archival record, belong at the core of this story. In the course of the seventeenth century, the silver economy expanded, and it was New Mexico’s misfortune to function as a reservoir of coerced labor and a source of cheap products for the silver mines. It did not take the bad behavior of too many Spanish governors, friars, and colonists—compelling Indians to carry salt, robbing their pelts, locking them up in textile sweatshops, and organizing raiding parties to procure Apache slaves—to bring about widespread animosity, resentment, and ultimately rebellion.

32

The case of the Pueblo Revolt as a rebellion against the other slavery rests on three types of evidence. The first comprises testimonies of Pueblo rebels. The Spaniards had few opportunities to learn about the causes of the rebellion during their hasty exodus from New Mexico. A year and a half would pass before they were able to gather additional intelligence. At the end of 1681, Governor Otermín led a group of Spanish soldiers and colonists back to New Mexico. During this foray, they were able to capture nine Pueblo Indians, who were brought before the governor for questioning. Their depositions were recorded over a two-week period in late December 1681 and early January 1682. Understandably, Pueblo captives were vague when asked pointedly about the “cause and reasons that led all the Indians of this kingdom to rise up.” Still, out of the eight extant testimonies, four contain concrete references to Spanish exploitation. An eighty-year-old Indian from San Felipe named Pedro Naranjo, for example, declared that in the wake of the insurrection, the Indians had remained “free from the work requested by the friars and the other Spaniards which they could no longer bear, and that this was the real reason and legitimate cause that they had to rise up.” A twenty-year-old

ladino

(Hispanicized) Indian named Joseph similarly declared that “the causes generally given were the ill treatment and abuses that the Indians received from the current

secretario

Francisco Xavier and the

maestro de campo

Alonsso Garcia and the

sargentos mayores

[sergeant majors] Luis de Quintana and Diego López because they had hit them and taken away what they had and made them work without paying them anything.” Two other prisoners, brothers Juan and Francisco Lorenzo, also named Francisco Xavier as a major reason for the rebellion. These few surviving testimonies may be too slender a reed on which to hang an interpretation of the overall rebellion, but they are very suggestive nonetheless.

33

The timing of the insurrection also lends credence to the theory that Indian slavery was the cause of the rebellion. As already noted, the Pueblo Revolt was long in the making. On at least three different occasions between 1650 and 1680, the Pueblos had attempted to launch a unified movement against their Spanish overlords. Yet this period of Pueblo insurgency is puzzling because it was characterized by relative demographic stability. A few sources mention famines and epidemics, particularly toward the late 1660s. But this famine/pestilence episode

does not jibe with the upheaval of 1680. At least to my knowledge, there is not a single testimony claiming that the Pueblos rebelled in 1680 or 1681 because of famine or pestilence. However, this thirty-year period of Pueblo unrest corresponds admirably with the deepening of commercial ties between New Mexico and the silver mines of northern Mexico. Since its founding in 1631, Parral had attracted resources and peoples to its flourishing mines. As we have seen, New Mexican officials and private citizens responded to these new economic opportunities by stepping up the seizure of Indian products, pressing Natives into New Mexican textile sweatshops, or raiding Apache rancherías to procure slaves. The Indian slave trade blossomed during the 1650s, 1660s, and 1670s—precisely when the Pueblo Indians were plotting against the Spaniards.

34

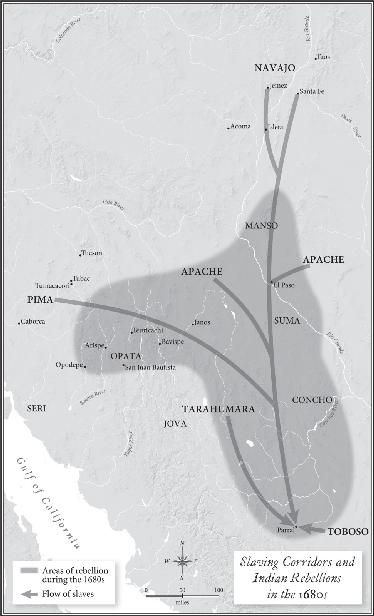

The last body of evidence that suggests that the Pueblo Revolt was triggered by labor coercion has to do with the ethnic and geographic scope of the insurrection. Though generally known as the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the movement in fact spread far beyond New Mexico and came to involve not only Pueblos but also the Apaches, Mansos, Conchos, Sumas, Pimas, Janos, Salineros, Tobosos, and many other groups. Some scholars even refer to this multiethnic insurrection as the Great Northern Rebellion. But regardless of labels, the geography of the revolts of the 1680s and early 1690s is quite intriguing. Broadly speaking, the rebellion spread along two corridors, one running due south from New Mexico into the El Paso–Janos area then on through central and southern Chihuahua “to the doors of El Parral and La Vizcaya,” and the other extending west into what is today Arizona and Sonora to the mines of San Juan Bautista, Opodepe, and Teuricachi. What these regions and their indigenous inhabitants had in common was that they had all been subjected to the gravitational pull of the silver economy. The geography of the rebellion maps exceedingly well onto the slaving corridors leading to Parral.

35

Explaining the motives of peoples in times that are remote from our own is a dicey business. And, of course, rebellions are seldom triggered by a single cause. Still, it is remarkable how writers and historians

have accorded Indian slavery so modest a role in their explanations of the Pueblo Revolt. Without a doubt, however, the rebellions that raged through much of the 1680s and 1690s redefined labor relations in northern Mexico. Indians in New Mexico, Chihuahua, Durango, Sonora, and Coahuila challenged slavery and forced important changes in the ways the traffic of humans was conducted in the following century.

36

7

Powerful Nomads

N

ATIVE AMERICANS WERE

involved in the slaving enterprise from the beginning of European colonization. At first they offered captives to the newcomers and helped them develop new networks of enslavement, serving as guides, guards, intermediaries, and local providers. But with the passage of time, as Indians acquired European weapons and horses, they increased their power and came to control an ever larger share of the traffic in slaves.

Their rising influence was evident throughout North America. In the Carolinas, for instance, English colonists took tens of thousands of Indian slaves and shipped many of them to the Caribbean. In the period between 1670 and 1720, Carolinians exported more Indians out of Charleston, South Carolina, than they imported Africans into it. As this traffic developed, the colonists increasingly procured their indigenous captives from the Westo Indians, an extraordinarily expansive group that conducted raids all over the region. Anthropologist Robbie Ethridge has coined the term “militaristic slaving societies” to refer to groups like the Westos that became major suppliers of Native captives to Europeans and other Indians. The French in eastern Canada had a similar experience. They procured thousands of Indian slaves during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but as they moved away from Quebec and Montreal and into the Great Lakes region and upper Mis

sissippi basin, they encountered a world of bondage they could scarcely comprehend, let alone control. Indians preyed on one another to get captives whom they offered to the French in exchange for guns and ammunition and to forge alliances. Throughout North America, Natives adapted to the sprawling slave trade and sought ways to profit from it.

1

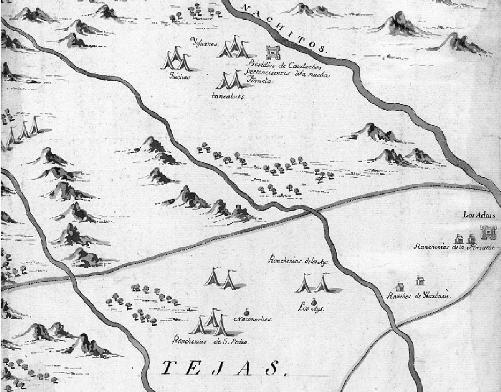

One can learn much about frontier regions through maps. José de Urrutia’s 1769 map of northern Mexico, for example, identifies towns, missions, ranches, and presidios—unmistakable evidence of Europe’s march into the region—while also making clear that Indian nations (rancherías) held sway over vast swaths of this territory. In the eighteenth century, the frontier was still a patchy grid of European enclaves overlaid on a sea of indigenous peoples.

The most dramatic instances of Indian reinvention occurred in what is now the American Southwest. Multiple factors propelled Indians of this region to become prominent traffickers. The royal antislavery activism of the Spanish crown and the legal prohibitions against Indian slavery dissuaded some Spanish slavers of northern Mexico, leaving a void that others filled. Moreover, the Indian rebellions of the seventeenth

century that culminated in the Great Northern Rebellion restricted the flow of Indian slaves from some regions and led to the opening of new slaving grounds, creating new opportunities. Most important, the diffusion of horses and firearms accelerated at this time, giving some Indians the means to enslave other people. Thus new traffickers, new victims, and new slaving routes emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Some Native communities experienced a process of “deterritorialization,” as Cecilia Sheridan has called it, becoming unmoored from their traditional homelands, fusing with other groups, and reinventing themselves as mobile bands capable of operating over vast distances. They made a living by trading the spoils of war, including horses and captives.

2

The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 succeeded in expelling the Spaniards from New Mexico. When the colonists returned in 1692, the world as they had known it had changed during their twelve-year absence. The returning Spaniards noticed that the Pueblo Indians had forged closer ties with the surrounding nomads. When the Spaniards approached the pueblo of Jemez, for example, they were greeted by a mixed force of Pueblos and Apaches. Once inside the pueblo, the Spanish leader, Diego de Vargas, spotted Apache warriors walking about freely. Other Spaniards observed much the same situation in various parts of the Pueblo world. At the Hopi pueblo of Walpi, in northeastern Arizona, several Indian nations made a show of force. “Some of them were of the Ute nation,” Vargas recorded in his diary, “and others were Apaches and Coninas [Havasupais], and all of them were the allies and neighbors of the Hopi pueblos.” The colonists thus encountered a tangle of newly forged alliances. Each pueblo had become like the hub of a wheel connected through the spokes to various bands of hunter-gatherers. The easternmost pueblos of Pecos and Taos befriended Apache bands that lived farther to the north and east, while the Hopi pueblos of Acoma and Jemez, in western New Mexico, developed alliances with groups of Navajos and Utes.

3