Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) (39 page)

Read Triumph and Tragedy (The Second World War) Online

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Triumph and Tragedy

242

isthmus was sealed off, and plans could be made for continuing the operations westward towards Walcheren.

This hard task was undertaken by the 2d Canadian Division, which forced its way westward through large areas of flooding, their men often waist-deep in water. They were helped by the greater part of the 52d Division, who were ferried across the Scheldt and landed on the south shore at Baarland. By the end of the month, after great exertions, the whole isthmus was captured. Meantime the last pockets of enemy on Breskens “island” were being eliminated and all was set for the Walcheren attack. The Canadian Army’s success was an essential preliminary to more spectacular operations. In four weeks of hard fighting, during which the 2d Tactical Air Force, under Air Marshal Coningham, gave them conspicuous support, they took no fewer than 12,500

German prisoners, who were anything but ready to surrender.

The island of Walcheren is shaped like a saucer and rimmed by sand-dunes which stop the sea from flooding the central plain. At the western edge, near Westkapelle, is a gap in the dunes where the sea is held by a great dyke, thirty feet high and over a hundred yards wide at the base.

The garrison of nearly 10,000 men was installed in strong artificial defences, and supported by about thirty batteries of artillery, some of large calibre in concrete emplacements.

Anti-tank obstacles, mines, and wire abounded, for the enemy had had four years in which to fortify the gateway to Antwerp.

Early in October the Royal Air Force struck the first blow. In a series of brilliant attacks they blew a great gap, nearly four hundred yards across, in the Westkapelle dyke.

Triumph and Tragedy

243

Through it poured the sea, flooding all the centre of the saucer and drowning such defences and batteries as lay within. But the most formidable emplacements and obstacles were on the saucer’s rim, and their capture, already admirably described,

4

can be told here only in outline. The attack was concentric. In the east the 2d Canadian Division tried to advance from South Beveland over the connecting causeway, and finally seized a bridgehead with the help of a brigade of the 52d Division. In the centre, on November 1, No. 4 Commando was ferried across from Breskens and boldly landed on the sea-front of Flushing. This first wave was followed rapidly by troops of the 52d Division, who battled their way into the town. The main attack was from the west, launched by three Marine Commandos under Brigadier Leicester. Embarking at Ostend, they sailed for Westkapelle, and at 7 A.M. on November 1 they sighted the lighthouse tower. As they approached the naval bombarding squadron opened fire.

Here were H.M.S.

Warspite

and the two 15-inch-gun monitors

Erebus

and

Roberts,

with a squadron of armed landing craft. These latter came close inshore, and, despite harsh casualties, kept up their fire until the two leading Commandos were safely ashore. No. 41, landing at the northern end of the gap in the sea-wall, captured the village of Westkapelle and drove on towards Domburg. No. 48, landing south of the gap, soon met fierce resistance.

Invaluable though the naval covering fire had been, a principal adjunct was lacking. A heavy bombardment had been planned for the previous day, but mist prevented our aircraft from taking off. Very effective fighter-bomber attacks helped the landing at a critical moment, but the Marines met much stronger opposition, from much less damaged defences, than we had hoped.

Triumph and Tragedy

244

That evening No. 48 Commando had advanced two miles along the fringe towards Flushing, but was held up by a powerful battery embedded in concrete. The whole of the Artillery of the 2d Canadian Army, firing across the water from the Breskens shore, was brought to bear, and rocket-firing aircraft attacked the embrasures. In the gathering darkness the Commando killed or captured the defenders.

Next morning it pressed on and took Zouteland by midday.

There No. 47 took up the attack, and, with a weakening defence, reached the outskirts of Flushing. On November 3

they joined hands with No. 4 Commando after its stiff house-to-house fighting in the town. In a few days the whole island was in our hands, with 8000 prisoners.

Triumph and Tragedy

245

Triumph and Tragedy

246

Many other notable feats were performed by Commandos during the war, and though other troops and other Services played their full part in this remarkable operation the extreme gallantry of the Royal Marines stands forth. The Commando idea was once again triumphant.

Minesweeping began as soon as Flushing was secure, and in the next three weeks a hundred craft were used to clear the seventy-mile channel. On November 28 the first convoy arrived, and Antwerp was opened for the British and American Armies. Flying bombs and rockets plagued the city for some time, and caused many casualties, but interfered with the furtherance of the war no more than in London.

Antwerp’s ordeal was not the only reason for trying to thrust the Germans farther away. When the 2d Canadian Division swung west into South Beveland there were still four German divisions in a pocket south of the river Meuse and west of the Nijmegen corridor. It was an awkward salient, which by November 8 was eliminated by the Ist and the XIIth Corps.

5

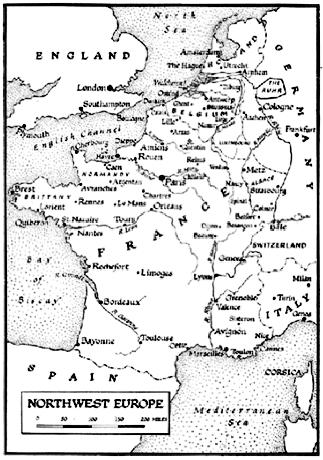

On the other flank of the Nijmegen corridor there was still an obstinate enemy, west of the Meuse, in a pocket centred on Venlo. Farther south the First U.S. Army breached the Siegfried Line north of Aachen in the first week of October. The town was attacked from three sides and surrendered on October 21. On their flank the Third Army were twenty miles east of the Moselle. The Seventh Army and the First French Army had drawn level and were probing towards the High Vosges and the Belfort Gap. The Americans had all but outrun their supplies in their lightning advances of September, and a pause was essential to build

Triumph and Tragedy

247

up stocks and prepare for large-scale operations in November.

The Strategic Air Forces played a big part in the Allied advance to the frontiers of France and Belgium. In the autumn they reverted to their primary role of bombing Germany, with oil installations and the transportation systems as specific targets. The enemy’s radar screen and early-warning system had been thrust back behind his frontier, and our own navigation and bombing aids were correspondingly advanced. Our casualty rate decreased; the weight and accuracy of our attacks grew. The long-continued onslaught had forced the Germans to disperse their factories very widely. For this they now paid a heavy penalty, since they depended all the more on good communications. Urgently needed coal piled up at pitheads for lack of wagons to move it. Every day a thousand or more freight trains were halted for lack of fuel. Industry, electricity, and gas plants were beginning to close down. Oil production and reserves dropped drastically, affecting not only the mobility of the troops, but also the activities and even the training of their air forces.

In August Speer had warned Hitler that the entire chemical industry was being crippled through lack o: by-products from the synthetic oil plants, and the position grew worse as time went on. In November he reported that if the decline in railway traffic continued it would result in “a production catastrophe of decisive significance,” and in December he paid a tribute to our “far-reaching and clever planning.”

6

At long last our great bombing offensive was reaping its reward.

Triumph and Tragedy

248

14

Prelude to a Moscow Visit

Progress of the Russian Offensive

—

The Red

Army Reaches the Baltic— The Liberation of

Belgrade, October

20 —

My Desire for Another

Meeting with Stalin — The Future of Poland and

Greece — The World Organisation and the

Deadlock at Dumbarton Oaks — Telegrams from

General Smuts, September

20, 26,

and

27 —

I

Plan a Visit to Moscow — Correspondence with

the President — Stalin Sends a Cordial Invitation,

September

30 —

Russia and the Far East — I

Start for Moscow, October

5 —

The Campaign in

Italy.

T

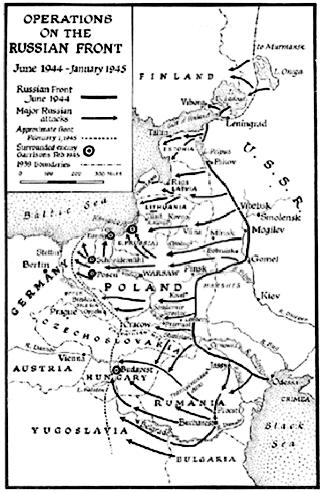

HE STORY of the immense Russian offensive of the summer II of 1944 has been told in these pages only to the end of September, when, aided by the Rumanian revolution, the Soviet armies drove up the valley of the Danube to the frontier of Hungary and paused to consolidate their supply. We must now carry it forward to the end of the autumn.

1

We followed with deep interest and growing hopes the fortunes of this tremendous campaign. The German garrisons in the northern Baltic States had been practically cut off by the Russian advances far to the south, and were extracted with difficulty. The first attacks fell upon them in mid-September from either end of Lake Peipus. These Triumph and Tragedy

249

spread swiftly outward, and in three weeks reached all the Baltic shore from Riga to the north.

On September 24 the southern front again flared into activity. The offensive began with an advance south of the Danube into Yugoslav territory. The Russians were supported on their left flank by the Bulgarian Army, which had readily changed sides. Jointly they made contact with Tito’s irregular forces and helped to harry the Germans in their hard but skilful withdrawal from Greece. Hitler, despite the obvious dangers impending in Poland, set great store on the campaign in Hungary, and reinforced it obstinately.

The main Russian attack, supported by the Rumanian Army, began on October 6, and was directed on Budapest from the southeast, with a subsidiary thrust from the Carpathians in the north. Belgrade, by-passed on both banks of the Danube, was liberated on October 20 and its German garrison annihilated.