Women's Bodies, Women's Wisdom (39 page)

Read Women's Bodies, Women's Wisdom Online

Authors: Christiane Northrup

Tags: #Health; Fitness & Dieting, #Women's Health, #General, #Personal Health, #Professional & Technical, #Medical eBooks, #Specialties, #Obstetrics & Gynecology

Of course menstrual empowerment doesn’t end with a coming-of-age ceremony. Learning to embrace our bodies, our cycles, and our sexuality is an ongoing process. Many of today’s teenage girls are precocious “fertile time bombs” because they have no knowledge of their own cycles and use sexuality and intercourse as a rite of passage.

82

I advocate teaching all teenage girls how to make love to themselves, so that they don’t feel the need for teenage boys for an outlet. When we teach our young women respect for their bodies and for their cycles, and when we heal ourselves in these areas as well, we help break the cycles of abuse that have gone on for centuries.

After reading a newspaper article on Patricia Reis’s work with the Goddess and women’s bodies, Marge Rosenthal remembered that she had introduced the menstrual cycle to her daughter by creating a myth. In a letter to Reis she wrote, “When my daughter was four or five and I was premenstrual and searching for something positive about cramps, grouchiness, and all the other pleasures of being a woman, I created the Goddess Menses. She came out of a spontaneous situation: Mama grouchy, a kid wondering why, and me grasping for a believable answer.

“I told her that once a month the Goddess Menses visited a woman’s body, and that she was a very mysterious goddess. Sometimes she sneaked in without us knowing, and sometimes she announced herself with powerful tuggings inside our bodies. I told her that when men bleed it is always a sign of illness or injury, but that the bleeding the goddess brought was a reaffirmation of life. A cleansing of our body. I told her that the goddess’s arrival is a time of celebration, a time to buy flowers or something small and special, just for us women.

“I told her the grouchiness was because I wasn’t listening to my body. Had I felt the tuggings, I would have known to be extra loving to myself (and perhaps taken a couple of aspirin). As a result of my doing this, I saw all the positive value of creating our own goddesses. I created a little goddess to make positive association with the men strual cycle. She is a high-spirited, energetic goddess who plays tricks with our bodies, arriving early or late, quiet or stormy, tagging or rolling over us, but once her presence is acknowledged she is very happy to quietly settle down and wait—until next time.

“As I approach menopause I will miss the goddess. It will be a time of her holding on to the youth we shared and me letting go to let the next spirit enter my body. I wonder what her name will be?”

Creating Health Through the Menstrual Cycle

Sitting quietly, ask yourself, “What is my personal truth about the menstrual cycle? How am I feeling about this information? What messages about menstruation and hormones have I learned from my family? What information have I handed down to the younger women in my life? What do I tell myself about my menstrual period? What can it teach me?” Regardless of where you are, be gentle with yourself.

For the next three months, keep a moon journal specifically for noticing the effects of your menstrual cycle on your life. Keep track of the phases of the moon. (These are often listed in the newspaper or in an almanac.) See if you notice any correlation between your cycle and the phases of the moon. See if you crave certain foods premenstrually. What are they? Would taking a long bath feel as good as eating that hot fudge sundae?

Give yourself time to tune in to and reclaim your cyclic nature. Write a short journal entry every day. The rewards of doing this will be beyond measure. You’ll feel connected to life in a whole new way, with increased respect for yourself and your magnificent hormones.

Celebrate the Goddess Menses in your own unique way, knowing that doing so will improve your life on all levels.

The oldest oracle in Greece, sacred to the Great Mother of earth, sea, and sky, was named Delphi, from

delphos,

meaning “womb.”

—Barbara Walker,

The Women’s Encyclopedia

of Myths and Secrets

T

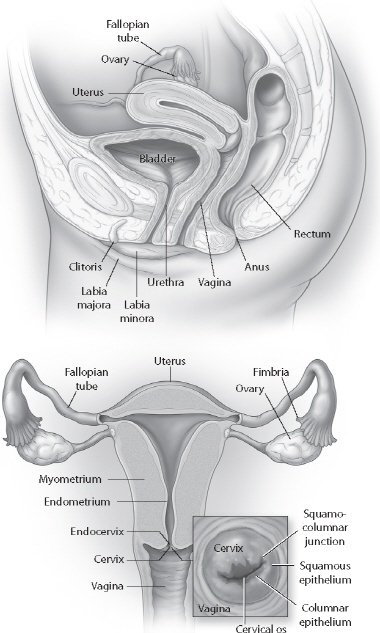

he uterus is located in the low center of the pelvis, in the middle of the pelvic bowl. Also known as the

hara,

this low-belly body center (which includes the ovaries, too) is associated with power, passion, and creativity. This makes sense because the uterus is the ves sel in which new life is nourished and brought to fruition. The uterus is connected to the vagina by the cervix and to the pelvic side walls by the broad and cardinal ligaments. The back portion of the bladder attaches to the lower front part of the uterus—the lower uterine segment. The fallopian tubes come off each side of the upper portion of the uterus, known as the fundus. The ovaries are located below the ends of the tubes, known as the fimbria. The fimbria look like delicate fern fronds. (see

figure 9

, page 165.)

The ovaries, tubes, and uterus are all part of the female hormonal system. Each of these structures is intimately connected to the others. The circulation of blood to the ovaries depends in part on the intact uterus. Following a hysterectomy, changes in the blood supply to the ovaries result in an earlier menopause in many women. The uterus itself is very sensitive to the effects of hormones. As the central organ in the pelvis, the uterus and its attachments to the pelvic side walls, the cardinal ligaments, are important but underrated components of the entire pelvic anatomy.

FIGURE 9: UTERUS, OVARIES, AND CERVIX WITH ANATOMIC LABELS

The uterus has hardly been studied separate from its role in child bearing, a fact that reflects this society’s baseline cultural biases.

1

The uterus is seen as someone else’s potential home and is valued when it can potentially play that role. After the uterus’s childbearing function has been completed or when a woman chooses not to have a child, modern medicine considers the uterus to have no inherent value. The ovaries usually have been viewed in much the same way because medical sci ence believes that hormonal replacement from artificial sources can perform their functions as well as or even better than a woman’s own organs. For centuries, women have been taught to view themselves in the same way, too—valuable as someone’s mother or mate, with no inherent value of their own.

When I was in my residency training, one of our oncology fellows (a doctor doing specialty training in gynecological cancer) taught us, “There’s no room in the tomb for the womb.” Another slogan from my training was: “The uterus is for growing babies or for growing cancer.” Occasionally, during my training, when one of our staff physician teachers removed a uterus that looked perfectly normal, we’d jokingly call the diagnosis CPU, a medicalized acronym for “chronic persistent uterus.” These attitudes have pervaded conventional medicine for years, but now they are rapidly changing.

The possibility that the uterus might have any function other than childbearing or tumor production has only recently begun to be ad dressed in conventional ob-gyn training. Up until just a few years ago, if a woman with a fibroid wanted to keep her uterus even though she had no interest in childbearing, her medical team might have viewed her as overly emotional or sentimental, a bit superstitious, and not well educated about that organ. The general dismissive tone of some doctors was that if such a woman were more sophisticated, she would know that the uterus is useless to her except for childbearing.

For example, I once did a fibroid removal from the uterus of a forty-eight-year-old woman who didn’t want a hysterectomy. The chief resident who assisted me said, “Why don’t you just do a hysterectomy? They can have my uterus anytime they want. Now that I’ve had my children, it’s only good for growing cancer.” I told her she’d been brainwashed.

In truth, the uterus plays a role in hormonal regulation, sexual satisfaction, and also bowel and bladder function (see section later in this chapter on hysterectomy, pages 194–197). Its removal is not advisable unless absolutely necessary.

This undervaluing of the uterus by doctors and the public alike has contributed to the fact that, after cesarean section, hysterectomy is the second most commonly performed major surgical operation in the United States. In the 1980s about 60 percent of women had their uterus removed by age sixty-five.

2

The average age of a woman undergoing hysterectomy is 46.1 years.

3

The rate of hys terectomy varies by region of the country, with the South having the highest overall rate of this procedure and the Northeast the lowest. Hysterectomy historically has been performed more commonly on African American women than on Caucasian women and more frequently by male gynecologists than by female gynecologists. The number of hysterectomies performed peaked in 1985, when 724,000 operations were reported.

4

Since then the number has declined. In 2004, 610,000 women had hysterectomies (with women ages forty to forty-four having the highest rate, 12.5 per 1,000 women).

5

Even though the overall hysterectomy rate has gone down since 1985, rates have remained largely unchanged in the past decade, and more than one-third of all American women will have this procedure by the time they reach sixty.

6

A total of 20 million have had this operation already. Clearly, hysterectomy is still performed too often when other options are available. The incidence of hysterectomy for benign (noncancerous) conditions is five times higher in the United States than in Europe.

7

The number of hysterectomies won’t change significantly until women change their beliefs about their pelvic organs. Since our thoughts affect our bodies, the negative messages about the uterus that are reflected in the current statistics and which we internalize over a lifetime are associated with a large number of problems that women experience in this area.

8

Though there are distinct differences between the energies of the ovaries and those of the uterus, many women have problems in both at the same time. For example, many women whose ovaries are affected by endometriosis also have fibroid tumors in the uterus. It is helpful, therefore, to discuss in general the overall nature of the emotional and psychological energy patterns that create health and disease in the pelvic organs.

The

internal

pelvic organs (ovaries, tubes, and uterus) are related to second-chakra issues. And second-chakra issues are always related to money, sex, and power. Thus the health of the pelvic organs depends upon a woman’s feeling able, competent, or powerful enough to create both financial and emotional abundance and stability, and to express her creativity and sexuality fully. She must be able to feel good about herself and about her relationships with other people in her life. Relationships that she finds stressful and limiting, and which she feels she has no control over, on the other hand, may adversely affect her internal pelvic organs. Thus, if a woman stays in an unhealthy relationship or job because she feels she cannot support herself economically or emotionally, her internal pelvic or gans may be at increased risk for disease.

Disease is not created until a woman feels frustrated in her attempts to effect changes that she needs to make in her life. The likelihood and severity of disease in this area are related to how well the various other areas of her life are functioning. A supportive marriage and family life, for example, can partially compensate for a stressful job. A classic psy chological pattern associated with physical problems in the pelvis is that of a woman who wants to break free from limiting behaviors in her re lationships (with her husband or job, for example) but who cannot confront her fears about the independence that making that change would bring. Though she may perceive that

others

are limiting her ability to break free, her major conflict is actually within herself around her

own

fears. One of my patients developed a fibroid tumor of the uterus and an ovarian cyst when she was forty. I asked her if her need for creativity was being met, and she told me that she very much wanted to leave her job and begin a florist business. She’d been interested in flowers since child hood, but her parents always discouraged her interest, since they considered it “frivolous.” She had dutifully gone along with their suggestion that she learn typing and secretarial skills instead. She eventually became an executive secretary in an accounting firm. Though this work was not satisfying to her, she stayed at her job because it provided her with a steady income and good benefits, and she was afraid of the risks of strik ing out on her own. As her fortieth birthday approached, she felt the need to pursue her childhood passion and had recurrent dreams about fields of flowers that she couldn’t get to because they were fenced in by barbed wire. She came to see that through her ovarian cyst and fibroid uterus, her body’s birthing center was trying to tell her something.