Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (4 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Table 1.1

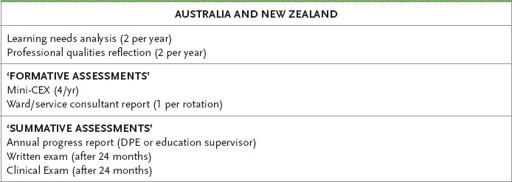

Summary of required teaching and learning activities and assessments under Physician Readiness for Expert Practice (PREP)

Mini-CEX Mini Clinical Evaluation Exercise

DPE Director of Physician Education

The written examination is described in more detail in

Chapter 2

. It is an examination of theoretical medical knowledge at a high standard. People who are serious about

physician training need to begin preparation for this examination at least 18 months before they sit. You will be eligible to sit the written and clinical examination after 24 months of certified basic training, i.e. in your third year.

Physicians are particularly concerned that patients’ treatment is of the highest standard and that physicians must have not only theoretical knowledge, but also the ability to assess patients clinically and come to a sensible diagnosis. This means being able to take a thorough history and expertly interpret the information, as well as perform an accurate physical examination. As a physician you should be able to manage patients as individuals who are all different from each other. There is continuing concern among senior physicians that too many doctors in practice do not take adequate histories, often perform rather cursory physical examinations (or none at all of the relevant system), and fail to consider a list of sensible differential diagnoses, to the patients’ detriment. Fundamentally it is our job to ensure our patients always come first. There has also been a disturbing trend to manage patients by

protocol

rather than by the use of skilled clinical assessment and judgement. An example would be the performance of a series of routine tests on every patient who complains of chest or abdominal pain, without making an attempt to assess the individual patient’s risks and circumstances to identify the relevant (and reversible) issues. Physician training is designed to educate physicians so that they do not practise in this way. This is why the

clinical examination

is as important as the written theoretical part (many in the College would argue the clinical examination is even more important than the written – it is certainly the most memorable part once passed).

The clinical examination for physician trainees is an extension of types of examination experienced by most undergraduate students. Currently the clinical examination is not based on a system of objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) (as arguably these are too rigid and fail to reflect complex clinical practice). Rather, it includes a more intense

short case

type of exam where the candidate’s ability to perform a rapid and accurate physical examination of a certain system or part of the body is observed by the examiners (15 minutes is allowed in the RACP clinical exam – this includes presenting the findings). The emphasis is on the detection of important clinical signs and the candidate’s approach to the patient. Candidates currently see four short case patients during a whole day of examination. This means

a number of different systems can and will be tested (e.g. a cranial nerve examination, assessment of gait, a heart murmur, palpation of abdominal masses, etc). It is usually very clear to the examiners when a candidate has sufficiently practised the particular examination asked for; these candidates look self-assured and smooth (even if they feel less than confident). This indeed is the point of the short case; to ensure candidates are practised in, and able to perform an examination of any part of the body with excellent technique that will identify, as reliably as is possible, key clinical signs, even if under stress. Successful candidates will have spent at least several months diligently practising their examination technique and seeing patients with a very large variety of clinical signs. A good trainee will have seen almost all important physical signs and will identify them on the test day.

The other component of the clinical exam that is also applied in most undergraduate medical programs is the

long case.

Each candidate will see two long cases during the RACP exam day. Here the candidate is left alone with the patient for an hour. Patients are chosen who have a number of different medical problems. These tend to be chronic problems such as ischaemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, inflammatory bowel disease, etc. The exam organisers are asked to find patients with two or three (or more) chronic medical problems and to include acute problems if possible! Candidates are expected to take a very detailed history from the patient and to perform an accurate examination. A summary of the patient’s history and examination findings is presented to the examiners (who have also seen the patient). They ask questions about management of the patient’s problems over 25 minutes. Again the emphasis is on treating the patient as an individual and not by protocol. This type of exam tests the general skills required by a physician. It is our view that the clinical examination is among the most rigorous in the world and the standard expected is appropriately high. Many argue this barrier exam explains the very high standard of physician practice in Australasia.

Success at the clinical examination is not recognised as a specialist qualification. To be admitted to Fellowship of the College requires success in both examinations and completion of basic and advanced training.

Determination to pass both the written and clinical examinations on the first attempt is an important part of preparation. The College has announced that candidates who pass the written examination must now pass the clinical examination within five years. From 2013 five failures signals the end of training. Thus a candidate who was successful in the written examination in 2015 has until 2020 to pass the clinical examination. Please refer to the College website for a full review of the rules and any updates. If you are an overseas trained physician it is essential to refer to the College website for more information about applying for the Fellowship.

There used to be no limit to the number of times candidates could sit the entire examination. Some persistent individuals sat many times (the record, we believe, is 11, and the candidate passed). More than 90 per cent of those who continue to sit do eventually get through, if they have the stamina. The pass rates for the last few years for the written and the clinical examination are both around 70 per cent, and the results are published by the College on their website.

HINT

Read the basic training curriculum and work on a study plan as soon as you start basic training!

There are a number of competencies that will be expected to have been achieved by the end of basic training (see the College website). Medical knowledge across a broad range of medical conditions and some depth in the specialities are key components, but not the only ones. Diagnosing and managing common medical problems (and knowing when to refer) is a skill you must acquire. Other core competencies include excellent communication skills with colleagues, patients and families (both oral and written), an understanding of the social determinants of health, including cultural awareness and the special needs of vulnerable groups (e.g. indigenous populations), and the ability to work in (and eventually lead) a multidisciplinary team that manages very complex medical problems. The highest level of professionalism will be expected of you as a physician.

We would argue there are additional competencies that should be acquired by consultant physicians over and above a very high level of clinical expertise, excellent communication skills and teamwork. Physicians should understand research methodology enough to be able to expertly interpret the ever-growing medical literature and include advances as appropriate in their clinical practice (doing and publishing research is the best way to acquire these skills). A lifelong love of learning remains an essential skill and maintaining competence will be an area of increasing attention for medical regulators. We would like to think that physicians are experts on the medical system and will become medical leaders who will advocate for appropriate system change in the interests of the community and all patients (‘medical systems engineering’). Who else is going to do it and do it well if we don’t?

This book was first published over 25 years ago as a guide to the FRACP exams. The basic skills needed for a candidate to perform well in short and long case examinations are also used by senior medical students and trainees in other specialties, including anaesthetics, emergency medicine, general practice and even psychiatry. The acquisition of the ability to take a history from patients accurately (and quickly) and examine remains as important today as it did when we started, despite the availability of better and better testing. We believe the approach set out in the rest of the book should be helpful for all practising clinicians who aspire to clinical excellence.

HINT

Refer to the College website for details of basic and advanced physician training, timing of examinations, and check for updates:

www.racp.edu.au

For further information, contact the following (from the College website):

Basic Training Units

The Basic Training Units in Australia and New Zealand are the first point of contact for any training-related enquiries.

Australia

Basic Training Unit

Education Services

The Royal Australasian College of Physicians

145 Macquarie Street

SYDNEY NSW 2000

Phone: +61 2 9256 5454

Email:

[email protected]

New Zealand

Basic Training Unit

PO Box 10601

WELLINGTON 6011

OR

4th Floor

99 The Terrace

WELLINGTON 6143

Phone: +64 4 472 6713

Email:

[email protected]

Trainees’ Committee

Australia

Email:

[email protected]

New Zealand

Email:

[email protected]

Medical Education Officers

Medical Education Officers (MEOs) are also available in each Australian state and New Zealand to answer queries and conduct on-site workshops.

Australia

Email:

[email protected]

New Zealand

Email:

[email protected]

Examinations Unit

Enquiries regarding applying for and sitting the written and clinical examinations should be directed to the Examinations Unit in Australia or the Basic Training Unit in New Zealand.

Australia

Email:

[email protected]

New Zealand

Email:

[email protected]

CHAPTER 2

The written examination

No man’s opinions are better than his information.

Paul Getty (1960)

The examination format

The written examination is a screening examination to select candidates for further testing. It is usually held in March in Australia and New Zealand. There are two papers, which are both taken on the same day. The written examination is an objective multiple-choice examination, with five choices in each question.

The first paper, Medical (basic) Sciences (Paper 1), is set with an emphasis on medical sciences and relevant basic science. It contains 70 questions to be answered in 2 hours. The majority of the questions are ‘A-type’ questions. There are five alternatives given, but only one is correct. Marks are not deducted for wrong answers and therefore it is no longer possible to score a negative mark for the total question. An incorrect or omitted answer will score zero. This is meant to encourage candidates to attempt to answer all questions. The second paper, Clinical Applications (Paper 2), contains 100 questions to be answered in 3 hours.

Extended matching questions (EMQ) are also included in both papers, and are aimed at testing problem-solving and clinical reasoning. Each EMQ comprises a theme which may be a symptom or sign, investigation, diagnosis or treatment. There are usually two or more clinical vignettes (the stems, typically a case history with symptoms, signs and/or test results). The problem includes an option list (i.e. eight possible answers from A to H, of which one is correct), and a lead-in question (such as: for each patient, choose the most useful test; or for each of these patients, select the most likely diagnosis). One answer is chosen for each stem.