Foundation Game Design with ActionScript 3.0, Second Edition (35 page)

Read Foundation Game Design with ActionScript 3.0, Second Edition Online

Authors: Rex van der Spuy

Add or change the following code in bold to the GameWorld.as file (we'll be taking a look at exactly how it works in the next section):

package

{

import flash.display.Loader;

import flash.display.Sprite;

import flash.events.MouseEvent;

import flash.net.URLRequest;

[SWF(width="550", height="400",

backgroundColor="#FFFFFF", frameRate="60")]

public class GameWorld extends Sprite

{

//All the variable declarations...

public function GameWorld()

{

//All the code that creates, displays

//and positions the objects...

//Add the button listeners

upButton.addEventListener(MouseEvent.CLICK, upButtonHandler);

downButton.addEventListener

(MouseEvent.CLICK, downButtonHandler);

}

public function upButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y = 100;

}

public function downButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y = 200;

}

}

}

The maximum line width for code examples in this book is 70 characters. However many lines of AS3.0 code you will write will be much, much longer than that. To make these code examples easily readable, without having to use a confusing line break character, I've implemented a simple formatting system for long lines of code.

I'm going to break long lines of code at an

operator.

Operators can mean any of these characters: ( ) = + - * / || !

I'll then indent by two spaces and continue the line of code at that point.

Here's an example from the program you just wrote. The following bit of code was too long to fit onto a single line:

downButton.addEventListener(MouseEvent.CLICK, downButtonHandler);

So I broke the line at the left parenthesis, started a new line, indented it by two spaces, and continued the code at that point:

downButton.addEventListener

(MouseEvent.CLICK, downButtonHandler);

How you space or indent your code won't make a difference to the way the program runs. Just remember that the semicolon will always tell you where the directive ends.

We're going to be writing some very long single lines of code in this book. I'll show you some strategies for formatting them so that they're easier to read as we encounter them.

Compile the program. Click the up and down buttons, and watch the character move up and down the stage.

Figure 3-40

shows you what you'll see.

Figure 3-40.

Click the buttons to move the character up and down the stage.

That's amazing, isn't it? Funny how such a simple little effect can be so satisfying to watch, especially after all the effort you've put into the program so far.

You should recognize much of the new code. You've created an event listener and a handler for the down button. And you've added two directives to the button event handlers to change the character'syposition property when the buttons are clicked.

The buttons work: they move my cat character up and down the stage. But the jump is quite big, and you can only move it back and forth between two positions. Wouldn't it be nice if you could move the character with small, gradual increments, and not be limited to two points? That would be a much more realistic effect and make the cat toy a little more fun to play with. Fortunately, this is very easy to do:

- Update the directives in the

upButtonHandleranddownButtonHandlerwith the following new text in bold:public function upButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y = character.y - 15;

}

public function downButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y = character.y + 15;

} - Compile the program. Click the up and down buttons again, and now the cat moves 15 pixels in either direction. Much better!

But how did this work? The logic behind it is very simple once you get your head around it. Let's have a look at thedownButtonHandler's directive:

character.y = character.y + 15;

This directive takes the currentyposition of the cat, adds 15 pixels to it, and then reassigns the new total back to the cat's currentyposition. Think of it this way: the cat's new position is a combination of its position before the button was clicked, plus 15 pixels. You want to move the cat down the stage, so you need to

increase

itsyposition.

I know, this is a bit of a brain- twister! Let's break it down a little more. The starting position of the character in my program is 150 pixels. Whenever the program seescharacter.y, it interprets that to mean “150 pixels.” You've set up the program so that every time the down button is clicked, 15 pixels are added to the character's y position. That's what this part of the directive in bold does:

character.y = character.y + 15;

It just adds 15 to the cat's y position, so the cat's new y position is 165. So you could actually write the directive this way:

character.y = 165;

Pretty simple, really, isn't it?

The next time the button is clicked, exactly the same thing happens, except thatcharacter.ynow starts with a value of 165 pixels. Fifteen pixels are added again, so the new value becomes 180. Each new button click adds another 15 pixels to the position, and the result is that the cat looks like it's gradually moving down the stage.

To help you come to grips with how this is working, add atracedirective to the event handlers in the program:

- Add the following code in bold to the

upButtonHandleranddownButtonHandler:public function upButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y = character.y - 15;

trace(character.y);

}

public function downButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y = character.y + 15;

trace(character.y);

} - Compile the program again.

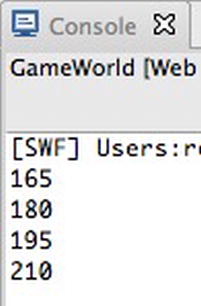

Click the down button a few times. Each time you click it, you'll see the new value of thecharacter.yproperty displayed as atracemessage. Although your numbers will be different, the effect will be similar to what you can see in

Figure 3-41

. The values increase by 15 with each click.

Clicking the up button produces numbers in the opposite direction as the character moves up the stage.

Figure 4-41.

The character's y position increases by 15 pixels with each click of the down button.

Using atracedirective is a great way to help you figure out what your code is doing, and you'll be using it a lot to help test and debug the projects in this book.

There's a slightly more efficient way to write this code. Updating values incrementally, as you've just done, is such a common and useful thing that AS3.0 has specialized operators that do the work for you.

Operators

are symbols such as =, -, + and *, which perform specialized tricks with values, such as assigning, adding, or subtracting them.

The two new operators that you'll use are called the

increment

and

decrement

operators. Let's update theupButtonHandleranddownButtonHandlerso that they use these operators:

- Change

upButtonHandleranddownButtonHandlerso that they match the code below. (I haven't included the trace directives, and you can remove them if you want to. Leaving them in is just fine too, it won't affect how the program runs.)public function upButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y-= 15;

}

public function downButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

character.y+= 15;

} - Compile the program and click the up and down buttons again.

The functionality of the program is exactly the same, but I simplified the code a bit by using the decrement operator:

-=

and the increment operator:

+=

These operators work by assigning the new value back into the original property. The -= operator subtracts the value, and the += operator adds it.

Incrementing and decrementing are a game designer's staple, so get used to using them because you'll be seeing them a lot from now on.

You might have noticed that there's no limit to how high or low the cat can go on the stage. In fact, you can make the character go all the way to the top of the stage and continue going beyond it endlessly. There is a kind of existential appeal to being able to model such an abstract concept as infinity in such a concrete way, but it doesn't help your game!

You have to limit the character's range by using a

conditional statement

. You can create a conditional statement using theifkeyword. The conditional statement checks to see whether the character'syposition is in an allowable range; if not, it prevents the directive in the event handler from running.

An if statement is very easy to implement. It's a block statement that you can drop anywhere in the program to check whether a certain condition is true. If the condition is true, the directives inside the block run. If they're false, they don't run.

Here's a plain English example of how an if statement works:

if (whatever is inside these parentheses is true)

{

... then run the directives inside these braces.

}

Let's use a real-world if statement in the methods you've just written to test it. We'll prevent our game character from moving beyond the top or bottom of the stage,

- Add the following code in bold to the program:

public function upButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

if(character.y> 0)

{

character.y -= 15;}

}

public function downButtonHandler(event:MouseEvent):void

{

if(character.y< 300)

{

character.y += 15;

}

} - Compile the program and try clicking the up and down buttons again. The character is now prevented from moving beyond the top and bottom of the stage. Exactly the effect we want to achieve!

Let's look at how the if statement works in the

upButtonHandler:if(character.y> 0)

{

character.y -= 15;

}

The key to making it work is the conditional statement inside the parentheses:

if(character.y> 0)

Conditional statements are used to check whether a certain condition is true or false. The preceding conditional statement is checking to see whether the y position of the cat is greater than 0.If the condition resolves as true, the directive it contains inside the curly braces is executed. Remember that 0 is the y value of the very top of the stage, and that the character's y position is measured from its top left corner.

Conditional statements use

conditional operators

to do their checking for them. The conditional operator used in the if statement is the

greater than

operator. It looks like this:

>

This operator checks whether the value on its left (the character's y position) is greater than the value on its right. there are many conditional operators available to use with AS3.0, and Table 4-3 shows the most common ones.