Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet (24 page)

Read Hope's Edge: The Next Diet for a Small Planet Online

Authors: Frances Moore Lappé; Anna Lappé

Tags: #Health & Fitness, #Political Science, #Vegetarian, #Nature, #Healthy Living, #General, #Globalization - Social Aspects, #Capitalism - Social Aspects, #Vegetarian Cookery, #Philosophy, #Business & Economics, #Globalization, #Cooking, #Social Aspects, #Ecology, #Capitalism, #Environmental Ethics, #Economics, #Diets, #Ethics & Moral Philosophy

Needless to say, very few unprocessed foods are advertised.

Does it make sense to say that the risky new American diet is what people

want

, when their choices are so heavily influenced by the corporations which have the most to gain by these choices?

PepsiCo and Nabisco and General Foods also benefit from the fact that although the sugar and salt in high-risk foods are not biologically addictive, as far as we know, they often seem to be psychologically addictive. From my own experience, from the experience of friends, and from dozens and dozens of letters I have received over the years, I’m convinced that “the more you eat, the more you want.” (On the other hand, the less you eat, the less you want.)

Whose Convenience?

The explosion of processed foods is frequently explained as a response to the needs of working women. “Working wives haven’t the time to cook, and they’ve got the money to pay a bit more for frozen foods,” is how

Forbes

puts it.

40

There is some truth to this, but the presumption is always that cooking with whole foods is more time-consuming than using “convenience” foods. Yet in my own experience this is simply not true, although it takes some extra time and thought to change habits in the beginning. If you know what to have on hand for easy meals, shop in a small whole-foods store (which takes much less time than a supermarket), and lay out your kitchen so that everything, including a few time-saving utensils, is within easy reach, whole-food cooking can be fast and convenient. (I discuss these points in more detail in Book Two.)

Thousands of processed foods and mammoth supermarkets purport to save us time. But do they really? Although the average time spent in preparing food in an urban household fell by half an hour between the 1920s and the late 1960s, we never really gained more free time, according to a

Journal of Home Economics

report.

41

With longer distances to stores, bigger stores, and other complexities of life, an extra 36 minutes each day were used in food marketing and record keeping. We actually lost 6 minutes!

Another reason processed foods have taken over is that they require less imagination. (There are no instructions on a raw potato, says Michael Jacobson, but there are on a box of instant potatoes.) While I believe people are inherently creative, so much in our culture stifles creativity. Uniform images of what is beautiful, acceptable, and of high status bombard us. And the easiest way to be sure that we don’t deviate from those images is to buy what is prepackaged and prepared. In cooking and eating whole foods, however, we break loose from these standardized images. By taking charge of our food choices, we gain confidence in our judgment and creativity. Feeling less like simpleminded followers of instructions in one area of our lives can help us feel capable of assuming responsibility in unrelated areas.

A Right or a Privilege?

The man I met at the party who claims that Americans are getting what they ask for also was concerned about any attempt to interfere with corporations’ “right” to advertise what they want, to whomever they want. “We can’t violate their First Amendment rights,” he said.

He got me thinking. When they advertise,

are

General Foods and Coca-Cola exercising their First Amendment rights? A lot of Americans would agree that they are. But, I wondered, should we include in the definition of “free speech” the capacity to dominate national advertising? Isn’t there something amiss in this definition of rights?

Perhaps the concept of “rights” should be limited to those powers or possibilities which are open to

anyone

. For example, our right to say what we think, to associate with whom we please, and to practice whatever religion we choose. These are rights. But actions such as advertising on TV, open only to those with vast wealth, should be called something else—perhaps “privileges.” For how many of us could spend $340 million a year for advertising, as General Foods does? The $20 million spent just to promote one new sugared cereal amounts to more than 40 times the entire budget of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, which has provided vital information for this book.

Ideally, I suppose, there would be no such privileges in a society. If it were impossible for everyone wanting to participate in an action to do so, some would be selected on the basis of merit or some other fair system open equally to everyone. But that is pretty dreamy. So what can we do in the present, when there

are

privileges because some are incomparably more wealthy than others?

We can work to limit the privileges of wealth and to make those with wealth and power accountable to us all.

In campaigns for public office, for example, we have already limited the privileges of wealth by limiting the size of any one contribution. Why not regard access to TV advertising the same way? If we placed a low ceiling on the amount of money that any one company could spend on TV advertising, this would diminish the privileges now held by a handful of giant corporations. As we have seen, it’s because the biggest corporations can spend such enormous sums on advertising that they can squeeze out the smaller producers—and then charge us more.

Once we realize that advertising is a privilege, not a right, isn’t it reasonable to grant that privilege only on certain conditions? An obvious condition would be that the advertising—with its proven power to influence—not be used to promote products that threaten our well-being. Society has already banned cigarette advertising on TV. There is virtually unanimous opinion in the health community that high-sugar, low-nutrition foods—those which monopolize TV advertising—threaten our health. So why not ban advertising of candy, sugared cereals, soft drinks, and other sweets?

As long as our society rewards wealth by allowing it such disproportionate ability to influence public opinion, we cannot build a genuine democracy in America. But our vision must extend beyond the need to make advertising responsible to society’s well-being. The theme of this book is that we must work toward more democratic decision-making structures governing all aspects of our resource use. Those who process and distribute our food must be accountable, not just to their shareholders but to a broad, representative, elected, and recallable group of Americans whose concerns are wider than expanding sales and increasing profits. Only through such structures can we put into action our choices affecting the health and well-being of our earth and our bodies.

Where Do We Begin?

If this vision of a genuine democracy seems a long way off, we might be tempted to give up. Or we might look around us for signs of change and ask, how can we support them? We might look at ourselves, at our own lives right now. To build a democracy in America, we must redistribute power. We can be part of that redistribution

right now

by taking greater and greater responsibility for our own lives and the problems right in our own communities. I have met and heard from thousands of people across the country who are realizing that the redistribution of power in America begins with them.

Michelle Kamhi is one. She lives in New York City’s Upper West Side. In 1978 she decided that if the diet in her son’s school lunchroom—Twinkies, white bread, and bologna—was to change, it was up to her. “But how to change things?” she wrote. “Answer: form a committee, however small. Our Nutrition Committee at first consisted of one other concerned parent and myself.” From these two parents grew an innovative program on teacher and parent education. Kindergartners tried making their own whole wheat flour and bread. Third-graders, who were studying “desert people,” experimented with Middle Eastern delicacies, using beans and whole wheat pita bread. So nutrition entered the classroom not as a negative “don’t” but as a positive and tasty “do.”

And nutrition entered the lunchroom, too, according to Michelle.

Raw carrot and celery sticks are displacing mushy canned vegetables. Fruits canned in syrup have been banished in favor of fresh fruits on most days; occasionally, unsweetened canned pineapple or applesauce is substituted. No more white bread; only whole wheat is served. And meats containing nitrates/nitrites have been banned, thanks to a school-wide poll of parents.

Nutrition also entered the regular curriculum:

The day my son came home with a vocabulary list of “glucose, maltose, dextrose, fructose, honey, corn syrup, etc.,” I could see that my efforts had begun to reap benefits close to home. His second-grade class’s assignment was to see how many packaged foods containing hidden sugar he could find at home. This was a perfect example of how teachers were using the information disseminated at the workshops.…

42

Learning about food was obviously a powerful first step for Michelle, and her decision to seize the power she had is changing hundreds, maybe thousands of lives.

I have heard from many other people like Michelle. In

Part IV

, “Lessons for the Long Haul,” I’ve tried to capture what their experiences have to teach us. But first let’s tackle the protein debate, because that was where

Diet for a Small Planet

—and the vision it embodies—began over ten years ago.

3.

Protein Myths: A New Look

H

AVING READ OF

the vast resources we squander to produce meat, you might easily conclude that meat must be indispensable to human well-being. But this just isn’t the case. When I first wrote

Diet for a Small Planet

I was fighting two nutritional myths at once. First was the myth that we need scads of protein, the more the better. The second was that meat contains the

best

protein. Combined, these two myths have led millions of people to believe that only by eating lots of meat could they get enough protein.

Protein Mythology

Myth No. 1: Meat contains more protein than any other food

.

Fact:

Containing 20 to 25 percent protein by weight, meat ranks about in the middle of the protein quantity scale, along with some nuts, cheese, beans, and fish. (Check the “quantity” side of

Figure 14

, “The Food/Protein Continuum.”)

Myth No. 2: Eating lots of meat is the only way to get enough protein

.

Fact:

Americans often eat 50 to 100 percent more protein than their bodies can use. Thus, most Americans could

completely eliminate

meat, fish, and poultry from their diets and still get the recommended daily allowance of protein from all the other protein-rich foods in the typical American diet.

Myth No. 3: Meat is the sole source for certain essential vitamins and minerals

.

Fact:

Even in the current meat-centered American diet, nonmeat sources provide more than half of our intake of each of the 11 most critical vitamins and minerals, except vitamin B12. And meat is not the sole source of B12; it is also found in dairy products and eggs, and even more abundantly in tempeh, a fermented soy food. Some nutrients, such as iron, tend to be less absorbable by the body when eaten in plant instead of animal foods. Nevertheless, varied plant-centered diets using whole foods, especially if they include dairy products, do not risk deficiencies.

Myth No. 4: Meat has the highest-quality protein of any food

.

Fact:

The word “quality” is an unscientific term. What is really meant is usability: how much of the protein eaten the body can actually use. The usability of egg and milk protein is greater than that of meat, and the usability of soy protein is about equal to that of meat. (Check the “Usability” side of

Figure 14

.)

Myth No. 5: Because plant protein is missing certain essential amino acids, it can never equal the quality of meat protein

.

Facts:

All plant foods commonly eaten as sources of protein contain

all

eight essential amino acids. Plant proteins do have deficiencies in their amino acid patterns that make them generally less usable by the body than animal protein. (See the “Usability” side of

Figure 14

.) However, the deficiencies in some foods can be matched with amino acid strengths in other foods to produce protein usability equivalent or superior to meat protein. This effect is called “protein complementarity.”

Myth No. 6: Plant-centered diets are dull.

Fact:

Just compare! There are basically five different kinds of meat and poultry, but 40 to 50 kinds of commonly eaten vegetables, 24 kinds of peas, beans, and lentils, 20 fruits, 12 nuts, and 9 grains. Variety of flavor, of texture, and of color obviously lies in the plant world … though your average American restaurant would give you no clue to this fact.

Myth No. 7: Plant foods contain a lot of carbohydrates and therefore are more fattening than meat. Fact:

Plant foods do contain carbohydrates but they generally don’t have the fat that meat does. So ounce for ounce, most plant food has either the same calories (bread is an example) or considerably fewer calories than most meats. Many fruits have one-third the calories; cooked beans have one-half; and green vegetables have one-eighth the calories that meat contains. Complex carbohydrates in whole plant foods, grain, vegetables, and fruits can actually aid weight control. Their fiber helps us feel full with fewer calories than do refined or fatty foods.

Myth No. 8: Our meat-centered cuisine provides us with a more nutritious diet overall than that eaten in underdeveloped countries

.

Fact:

For the most part the problem of malnutrition in the third world is not the poor quality of the diet but the inadequate quantity. Traditional diets in most third world countries are probably more nutritious and less hazardous than the meat-centered, highly processed diet most Americans eat. The hungry are simply too poor to buy enough of their traditional diet. The dramatic contrast between our diet and that of the “average” Indian, for example, is not in our higher protein consumption but in the amount of sugar, fat, and refined flour we eat. While we consume only 50 percent more protein, we consume eight times the fat and four times the sugar. Our diet would actually be improved if we ate more plant food.

In earlier editions of

Diet for a Small Planet

I concentrated on the “meat protein mystique,” explaining why the body needs protein, how protein is ranked according to its usability by the body, and how you can combine plant proteins to create a protein mix that is just as usable by the body as is meat protein.

But it was the possibility of combining two or more less-usable proteins to create one of a better “quality” that most intrigued me. This neat trick is called “protein complementarity” and is explained fully in the next chapter. It doubly intrigued me when I realized that such food combinations evolved as the mainstay of traditional diets throughout the world.

Virtually all traditional societies based their diets on protein complementarity; they used grain and legume combinations as their main source of protein and energy. In Latin America it was corn tortillas with beans, or rice with beans. In the Middle East it was bulgur wheat with chickpeas or pita bread felafel with hummus sauce (whole wheat, chickpeas, and sesame seeds). In India it was rice or chapaties with dal (lentils, often served with yogurt). In Asia it was soy foods with rice (in southern China, northern Japan, and Indonesia), or soy foods with wheat or millet (in northern China), or soy foods with barley (in parts of Korea and southern China). In each case, the balance was typically 70 to 80 percent whole grains and 20 to 30 percent legumes, the very balance that nutritionists have found maximizes protein usability.

“Anglo students in Tucson had always put down the Chicanos for their ‘starchy’ diet,”

Arizona Daily Star

reporter Jane Kay told me. “But after your book came out, the Chicanos felt vindicated because it showed that the food the Mexican people in Tucson eat—lettuce, cheese, tortillas, and beans—is better than the all-American hamburger and fries.”

When I first wrote

Diet for a Small Planet

in 1971, the idea that people could live well without meat seemed much more controversial than it does today. I felt I had to prove to nutritionists and doctors that because we could combine proteins to create foods equal in protein usability to meat, people could thrive on a nonmeat or low-meat diet. Today, few dispute that people can thrive on this kind of diet. In fact, more and more health professionals are actually advocating less meat precisely for health reasons, reasons I discussed in “America’s Experimental Diet.”

In 1971 I stressed protein complementarity because I assumed that the only way to get enough protein (without consuming too many calories) was to create a protein as usable by the body as animal protein. In combatting the myth that meat is the only way to get high-quality protein, I reinforced another myth. I gave the impression that in order to get enough protein without meat, considerable care was needed in choosing foods. Actually, it is much easier than I thought.

With three important exceptions, there is little danger of protein deficiency in a plant food diet. The exceptions are diets very heavily dependent on fruit or on some tubers, such as sweet potatoes or cassava, or on junk food (refined flours, sugars, and fat). Fortunately, relatively few people in the world try to survive on diets in which these foods are virtually the sole source of calories.

In all other diets, if people are getting enough calories, they are virtually certain of getting enough protein

. (Babies, young children, and pregnant women need some special consideration, which I’ll discuss later.) This is true because the vast majority of unprocessed foods can supply us with enough protein to meet our daily protein allowance without filling us with too many calories. In

Appendix D

I present a simple rule of thumb for judging any food as a protein source. There you’ll see that most plant foods excel—meaning that you could eat just one food and get enough protein.

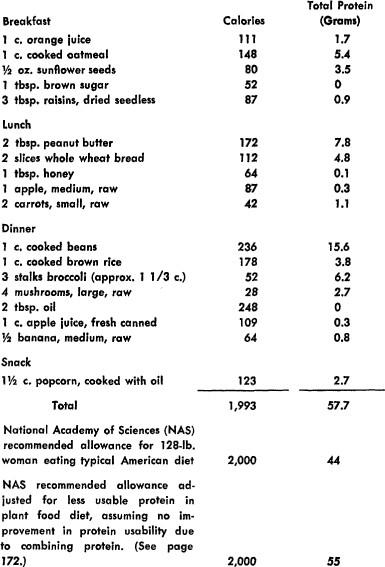

The simplest way to prove the overall point is to propose a diet which most people would consider protein-deprived and ask, does its protein content add up to the allowance recommended by the National Academy of Sciences? In

Figure 10

I have put together such a day’s menu—with no meat, no dairy foods, and no protein supplements. Even without accounting for improved protein usability due to combining complementary proteins, this diet has adequate protein without exceeding calorie limits.

10. Hypothetical All-Plant-Food Diet (Just to Prove a Point)

Clearly this diet contains much more protein, 57.7 grams, than the National Academy of Science’s recommendation of 44 grams of protein for an average American woman eating a typical American diet. But this allowance assumes that two-thirds of that protein is highly usable animal protein. Since my hypothetical daily menu contains no animal protein, and since I am trying to show that protein complementarity is not essential, let’s adjust the National Academy’s recommendation upward to what it would be for a plant food diet, assuming no protein complementarity. The allowance rises to about 55 grams. Yet my hypothetical diet

still

exceeds the allowance.

In the example, I used the weight and protein allowance of a typical American woman. But the same pattern would hold true for

any weight

person, since the protein allowance and calorie needs rise proportionately as body weight increases. For men, getting enough protein without exceeding calories limits is even a slight bit easier. (Men are allowed 2 more calories for every gram of protein than are women.)

Note that my hypothetical diet, while not intentionally protein-packed, is a healthy one. It contains few protein-empty foods, only sugar, honey, oil, an apple, and apple juice. They comprise only about 25 percent of the calories. The more of these protein-empty foods one eats, the more the rest of the diet should be filled with foods with considerable protein.

But a number of the world’s authorities on protein believe that the current recommended daily protein allowance may be too low. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, three-month-long experiments, with subjects consuming the recommended amount of protein in the form of egg, for most subjects resulted in the loss of lean body mass and a decrease in the proteins and oxygen-carrying cells of the blood.

If the recommended allowance were pushed up by one-third, as some scientists believe it should be, would it then be difficult to eat enough protein without meat?

The average American woman’s recommended allowance would then be 59 grams of protein. At this higher level, combining protein foods to improve the usability of the protein would become more important. But in this hypothetical day’s diet there are already complementary protein combinations (peanut butter plus bread, beans plus rice) which would bring the usability of the protein up closer to that assumed in the recommended allowance. To be totally safe, however, one might want to replace one of the protein-empty foods with an additional protein food if maintaining an all plant food diet. (For example, replacing the sugar and honey with grain or vegetable.)

Very few Americans, however, eat only plant foods. Even most vegetarians eat some dairy products. So in

Figure 11

let’s look at basically the same day’s diet but this time put in two modest portions of dairy foods, one cup of skim milk and a one-inch cube of cheese. These changes bring the total protein up to 71 grams—well above even the highest standard recommended by some nutritionists.

Protein Individuality

But scientists studying the differences in individual needs for nutrients warn us that even the most prudently arrived at recommendations, claiming to cover 97.5 percent of the population, should not be followed blindly.

R. J. Williams at the University of Texas is one of the best-known of these scientists. He points out that if beef were the only source of protein, one person’s minimum protein needs could be met by two ounces of meat; yet another individual might require eight ounces.

1

These two extremes represent a

fourfold difference

. The recommended allowance of the National Academy of Sciences nonetheless assumes that a twofold variation between the highest and the lowest needs will cover 95 percent of the population.) Donald R. Davis, also at the University of Texas, recently reviewed the literature on individual needs for amino acids, protein’s building blocks. Within small groups of subjects, differences ranged up to ninefold, states Davis.

2