Resident Readiness General Surgery (57 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Treatment of hypokalemia consists of oral or parental potassium supplementation. Oral formulations are preferred if the patient is able to take medications orally or is undergoing active diuresis. Intravenous potassium can be administered to patients unable to take po or those with severe hypokalemia (<2 mEq/L) at a rate of 10 mEq/h at a concentration no greater than 40 mEq/L. If repleting through a central line, it is permissible to replete at 20 mEq/h. Potassium can also be added to maintenance intravenous fluids at a concentration of 20 mEq in 1 L of fluid. As a general rule, administration of 10 mEq KCl, in either IV or po formulation, will increase the serum potassium level by 0.1.

It is important to note that hypomagnesemia antagonizes correction of hypokalemia. As such, if the patient is concomitantly hypomagnesemic, correction with magnesium supplementation must occur before potassium supplementation will correct hypokalemia.

Hyperkalemia

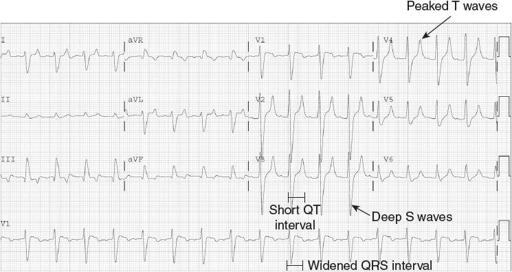

: Hyperkalemia is defined as a serum potassium concentration >5.5 mEq/L. Common causes of hyperkalemia include renal disease and a decreased ability to excrete potassium, crush injuries, rhabdomyolysis, ischemia–reperfusion injuries, adrenal insufficiency, succinylcholine administration, β-receptor agonists, digitalis, and excessive administration of intravenous fluids containing potassium. Early identification and treatment of hyperkalemia is imperative, as hyperkalemia has life-threatening consequences including cardiac arrhythmias and neuromuscular weakness leading to flaccid paralysis. EKG abnormalities include peaked T waves, QRS widening, shortened QT intervals, deepening of the S wave into a sinusoidal pattern, and ventricular ectopy followed by hypoexcitability presenting as asystole (see

Figure 43-2

). It can less commonly also lead to ventricular fibrillation.

Figure 43-2.

ECG abnormalities of hyperkalemia. (Reproduced, with permission, from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AB, Thurman RJ.

The Atlas of Emergency Medicine

. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010. Figure 23.45A. Photo contributor: R. Jason Thurman, MD. <

http://www.accessmedicine.com

>. Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All right reserved.)

Treatment of hyperkalemia consists of early stabilization of the myocardium and a temporary shift of potassium intracellularly, followed by elimination of potassium into the stool or urine. Initial temporizing treatment includes administration of 1 ampule of calcium gluconate, which acts to antagonize myocardial depolarization. Another temporizing treatment is the administration of sodium bicarbonate, especially if the patient is acidotic. Both measures antagonize the effects of hyperkalemia on the membrane potential and also facilitate the intracellular shift of potassium. Additionally, 10 U of insulin is given to shift potassium intracellularly. This is followed by 1 ampule of D

50

to thwart the impending insulin-induced hypoglycemia.

While the above measures will help reduce the serum potassium level, the effects are only transient. More definitive correction requires that potassium be excreted from the body. This is facilitated by administration of a loop diuretic (furosemide) or a sodium–potassium exchange resin (Kayexalate). Refractory hyperkalemia may ultimately require hemodialysis. A common mnemonic to remember how to treat hyperkalemia is “C-BIG-K-D,” or “See BIG Potassium Drop”:

C: Calcium gluconate

B: Bicarbonate (if acidotic)

I: Insulin

G: Glucose

K: Kayexalate

D: Dialysis

Hypomagnesemia

: Magnesium is an intracellular cation that serves as a cofactor in enzymatic reactions and is essential for protein synthesis, energy metabolism, and calcium homeostasis. Hypomagnesemia occurs when serum magnesium levels are <1.6 mg/dL. In the surgical patient this most commonly occurs secondary to hemodilution, but may also occur with chronically poor po intake, steatorrhea, biliary and enteric fistulas, or chronic use of loop diuretics. Severe hypomagnesemia places the patient at risk for lethal ventricular arrhythmias. Magnesium repletion should be considered if the magnesium level falls below 2.0. This may be done orally with magnesium citrate if the patient is able to take it. However, large doses will result in diarrhea and thus po repletion is generally neither necessary nor recommended in the acute hospital setting. Intravenous administration of magnesium sulfate is a better route of repletion for patients with severe hypomagnesemia and those unable to tolerate po.

Hypermagnesemia

: Hypermagnesemia is defined as a serum magnesium concentration >2.8 mg/dL. It is rare if the patient has normal kidney function, but may be seen in patients with burns, crush injuries, or those who require chronic hemodialysis. It may also be seen in pregnant women who are being administered magnesium sulfate as a tocolytic agent. Treatment starts with elimination of magnesium-containing medications. Calcium infusion at 5 to 10 mEq is administered to stabilize the myocardium, followed by normal saline to expand the intravascular compartment. Loop diuretics and hemodialysis may also be used to eliminate excess magnesium.

Hypophosphatemia

: Phosphorus is an important molecule in energy metabolism and ATP generation. Hypophosphatemia is defined as a serum phosphate concentration <2.5 mg/dL. It can be the result of renal failure and excessive renal losses, GI losses, diuretic use, major hepatic resection, or intracellular electrolyte shifts as occur in refeeding syndrome. Symptoms are related to ATP depletion and include cardiac and respiratory failure. Repletion should be considered when levels fall below 2.0 mg/dL, and this may be administered as NaPO

4

or KPO

4

(depending on the potassium level).

Hyperphosphatemia

: Hyperphosphatemia is defined as a serum phosphate concentration of >5.0 mg/dL. This is a rare postoperative occurrence but may be seen in renal failure, rhabdomyolysis, and tumor lysis syndrome. Treatment options include expanding the plasma volume with normal saline, administration of phosphate binders (aluminum-containing antacids), or, if severe and associated with renal failure, hemodialysis.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

Surgical patients are at risk for a variety of electrolyte disorders based on the pathophysiology of their disease states (emesis, diarrhea, NG tubes, fistulas, burns, trauma, wounds, etc) and anticipation of these abnormalities will greatly enhance treatment and management of these patients.

It is important to know the volume status in the hyponatremic patient, as treatment differs based on whether the patient is fluid overloaded or dehydrated.

Repletion of magnesium to normal levels is necessary before the patient will respond to potassium repletion.

Calcium rapidly stabilizes the myocardium in the hyperkalemic patient.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

In the case presented above, what are Ms. Jones’ anticipated electrolyte abnormalities?

A. Hypernatremia, hyperkalemia

B. Hyponatremia, hyperkalemia

C. Hypernatremia, hypokalemia

D. Hyponatremia, hypokalemia

2.

Ms. Jones’ chemistry panel revealed a serum sodium level of 130. How would you replete her deficit?

A. High-sodium diet

B. 2.5 L of 3% hypertonic saline over 48 hours

C. 2.5 L of NS over 24 to 48 hours

D. Free water restriction

3.

Which of the following is the initial treatment of severe hyperkalemia?

A. Insulin 10 U

B. Calcium gluconate 1 ampule

C. Kayexalate

D. Hemodialysis

Answers

1.

D

. Ms. Jones is hypovolemic and hyponatremic secondary to her GI losses. As a result, her renal plasma flow and GFR will be low, ultimately resulting in increased sodium reabsorption by the kidneys in exchange for potassium.

Other books

The Men With the Golden Cuffs by Lexi Blake

His Hometown Cowgirl by Anne Marie Novark

From the Cradle by Louise Voss, Mark Edwards

The Billionaire's Lesson by Anya Adonis

STARGATE SG-1: Do No Harm by Karen Miller

Por prescripción facultativa by Diane Duane

The Funny Man by John Warner

Kill Shot by Liliana Hart

Mistletoe Mine by Emily March

COLE (Dragon Security Book 1) by Glenna Sinclair