Wired for Love (12 page)

Authors: Stan Tatkin

Here are some supporting principles to guide you:

- Discover your partner. Using the examples presented in this chapter, find out what you may not yet know about your partner. What relationship style best describes your partner? And while you’re at it, what style best describes you? As I mentioned before, please resist the temptation to use this typology as ammunition against one another. Like any powerful tool, it can inflict damage if used improperly. So use it with compassion in your relationship.

- Be unapologetically you. Our task in committed relationships is not to change or become a different person. Quite the contrary: our task is to be unapologetically ourselves. Home is not a place to feel chronically ashamed or to pretend we are someone we’re not. Rather, we can be ourselves while retaining our sense of responsibility to others and to ourselves. And just as we are unapologetically ourselves, we must encourage our partner to be unapologetically himself or herself. In this way, we offer each other unconditional acceptance.

Of course, being unapologetically ourselves doesn’t mean we are reckless or uncaring about how we treat others, or that we can use this as an excuse to be our worst selves. For example, if your partner is unfaithful or otherwise hurtful to you, he or she can’t simply say, “Tough. This is who am. Just accept it.” No. This is a time when apology is definitely in order. In fact, whenever your partner voices hurt, you need to focus less on being unapologetically yourself and more on tending to your partner’s needs and concerns. Remember the first guiding principle:

creating a couple bubble allows partners to keep each other safe and secure.

Your mandate is to be unapologetically yourself as long as you also keep your partner safe. - Don’t try to change your partner. You could say that we all change, and also that we never change. Both are true. And this is why acceptance is so important. We can and do change our attitudes, our behaviors, and even our brains over time. However, the fundamental wiring that takes place during our earliest experiences stays with us from cradle to grave. Of course, we can change this wiring in phenomenal ways through corrective relationships. Sometime these changes transform all but the last remnants of our remembered fears and injuries. But this should not be the goal of a couple’s relationship. No one changes from fundamentally insecure to fundamentally secure under conditions of fear, duress, disapproval, or threat of abandonment. I guarantee that will not happen. Only through acceptance, high regard, respect, devotion, support, and safety will anyone gradually grow more secure.

Chapter 4

Becoming Experts on One Another: How to Please and Soothe Your Partner

When I see partners in a successfully maintained couple bubble, one standout feature is their ability to care for, influence, and manage one another, much the way expert parents do with their children. Both partners seem to have read and carefully studied the owner’s manual for their relationship and for each other. Each is familiar with operational details that no one outside of the bubble is likely to know.

For instance, these partners know what has the most power to push the other’s buttons. When the other is feeling bad, they immediately sense why. Not only that, they know how to remedy the situation. They know the right words to say, or deeds to perform, that have the power to elevate, relieve, excite, soothe, or heal each other. From a neuroscience perspective, these partners possess strong orbitofrontal cortices; well-balanced left and right brains; well-developed smart vagal systems; well-regulated breath and vocal control; and honed communication skills that keep love close and war at a far distance.

How did they get to be so adept? Are such people perhaps in possession of a perfect partner chromosome? Trust me, no. Do they have some kind of secret superpower that allows them to manage their partner emotionally? Well, maybe. As I said earlier, some of us got a better start in life than did others, with lots of positive interactions with safe adults who were interested in and curious about us. We all come to the table with primitives that don’t want us to be harmed, and ambassadors that at times can be annoying. Truth is, we can be, all of us, pains in the rear. When we recite our relationship vows, perhaps we should say, “I take you as my pain in the rear, with all your history and baggage, and I take responsibility for all prior injustices you endured at the hands of those I never knew, because you now are in my care.”

Hmm. How many people would be willing to say those vows? And yet, in my practice and research, that is exactly what I see couples in secure relationships doing. It is a conscious choice they make. They agree to take each other on “as is,” and take responsibility for one another’s care. As experts who understand their partner, they do what’s necessary to relieve the other’s distress or to amplify his or her elation. To many partners who find themselves at the mercy of each other’s moods, this kind of expertise may indeed seem like a secret superpower they’d do almost anything to obtain.

The role of primary partner is a big one: it entails taking good care of another human pain in the rear. And the only way for this to work is for it to be fully mutual. Both partners need to become experts on one another. With this kind of arrangement, nobody really loses and everybody truly wins. You can think of it as a kind of pay-to-play version of romance, and it is, make no mistake, an investment in your future.

The Three or Four Things That Make Your Partner Feel Bad

In fact, we all have a handful of issues with the particular power to make us feel bad. These issues typically originate during childhood, and we carry them into our adult relationships.

For instance, you may have been picked on as a child, and so you continue to feel vulnerable whenever someone tries to tease you. It affects you to this day. Or as a child, you were told you were ugly or stupid, and now you still feel you are less attractive or intelligent than others. Perhaps someone in your early childhood always had to be right, and by default always made you seem wrong. Today you continue to feel sensitive to right/wrong issues.

Here’s another scenario. Let’s say that during your childhood you experienced a great deal of chaos and disorganization from one or both parents. So lack of order currently upsets you, and you find yourself bothered by those who are careless, messy, and disorderly.

How many such issues does each of us actually have? Do they number in the tens? Or even more? Partners often are under the illusion that they have a vast storehouse of personal issues with which they have to deal. In my experience as a clinician, however, this is generally untrue. If we really boil our issues down to their essence, I’m willing to bet most of us will be able to identify only three or four with the power to make us feel bad. I believe most of us are disturbed by the same three or four vulnerabilities throughout our life.

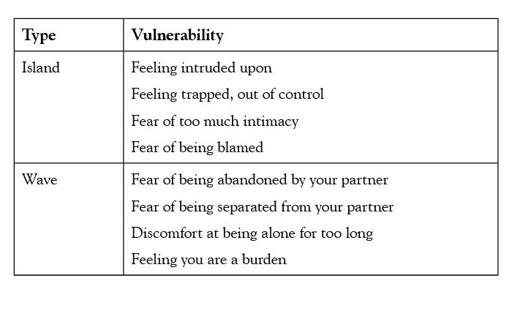

Table 4.1 lists some of the main vulnerabilities I have noticed among islands and waves. Note that I’m not including anchors here. This doesn’t mean they’re invulnerable, or that it’s unnecessary to soothe and please an anchor; however, on a daily basis, these partners are secure and their vulnerabilities are less pronounced.

Table 4.1 Common Vulnerabilities

Pushing Each Other’s Buttons

Peggy and Simon met at a church social ten years ago. Both recently widowed, they quickly took to one another and decided to live together. Now Simon is seventy, and Peggy sixty. Each was an only child and had a difficult childhood. Simon’s mother died at childbirth, and his father gave him up for adoption. His adoptive parents divorced a year later and handed him off to his maternal grandparents, who were already burdened with financial worries. Peggy’s father left when she was five, and her mother never remarried. Because her mother worked full time, Peggy went to her aunt’s house after school. This aunt, who had no children, often shut Peggy in a room by herself because this aunt “needed a little peace and quiet.”

The couple like to travel together, and they make frequent trips abroad. However, these often are marred by conflict. While in Europe recently, Simon lost track of Peggy at a train station. She went to get coffee, assuming Simon would wait on the train. But when she hadn’t returned after five minutes, he panicked and rushed into the station to look for her.

When they finally caught up with each other, Simon was livid. “Where were you?” he shouted, as Peggy approached with two coffees.

“What’s the matter?” she replied, a death glare on her face. “You’re embarrassing me.”

“I had no idea where you were!” Simon continued to shout. “The train’s about to leave. What were you thinking?”

Peggy didn’t respond. Still holding the coffees, she turned and entered the train, but a different car than the one where they had been sitting. Simon returned to his seat alone, angry and hurt that Peggy was ignoring him and unapologetic. He remained there until they reached their destination two hours later. By the time they met up on the platform, the tension between them seemed to have blown over, but the underlying issue was never discussed or resolved.

As a couple, Peggy and Simon are at the mercy of their three or four bad things. Neither is fully aware of the other’s issues from childhood or of how these vulnerabilities influence them in the present. In fact, they share at least one common issue: both were abandoned during childhood. In their adult relationships, this is reflected in difficulty trusting, fear, and general insecurity. Specifically, Simon’s main vulnerabilities are (1) believing he could be left at any time, (2) feeling he’s the cause of other people’s problems, and (3) suspecting others don’t trust him. Peggy’s vulnerabilities are (1) feeling she has to do everything alone, (2) believing she can’t count on anyone else, and (3) feeling uncomfortable with others’ expressions of emotion. By the way, from the information I’ve given thus far, were you able to discern that Peggy is an island, while Simon is a wave?

In the train incident, they both succeeded in pushing each other’s buttons, and neither did anything to relieve the other’s distress. Peggy showed insensitivity to Simon’s abandonment fears by not keeping him apprised of her whereabouts, and then acting incredulous at his anger. He, on the other hand, was insensitive to her withdrawal in the face of his upset, and unprepared to relieve her (and his own) suffering by gently approaching her to make amends.

I’m not suggesting Peggy and Simon intentionally hurt one another. That’s the last thing they want to do. The problem is that they don’t have the benefit of being experts on one another. In the dark about each other’s vulnerabilities and without the protection of a couple bubble, they continue to founder in hostile emotional territory. Their primitives have free rein much of the time, while their ambassadors remain helpless to regain the upper hand and repair the situation.

Exercise: How Are You Vulnerable?

As an expert on your partner, you need to be familiar with the three or four things that make him or her feel bad. But, as the saying goes, “Physician, heal thyself.” In other words, before attempting to identify your partner’s vulnerabilities, it makes sense to have a handle on your own.

So take a minute now and think about this.

- Sit down where you can have some private time, and think about the issues that have deeply affected you. From as early as you can remember, all the way to this point in time, what things still dog you today?

- It may help to recall specific incidents. For example, this could be an argument with your partner in which you became very angry, or a time you felt depressed, lonely, or rejected. In each incident, what was the issue that led you to feel vulnerable?

- Take a pen and paper (or your tablet PC) and jot down all the incidents and issues that come to mind. Don’t censor yourself.

- When you’ve completed your list, go back over it and look for commonalities. For example, suppose you recalled arguing with your partner after he or she leaked something private about the two of you to another couple, and you also recalled being mad as a teenager when your mother said things at the dinner table you had shared privately with her. Looking at both of these now, you see the common issue was feeling betrayed. See if you can narrow your list down to three or four main vulnerabilities.

- Focusing on your vulnerabilities might not be the most enjoyable of exercises. When you finish, do something nice for yourself (and your partner)!

Exercise: How Is Your Partner Vulnerable?

It is important for you to know your own vulnerabilities, and it is even more important to know your partner’s. Knowing your partner’s three or four bad things takes the guesswork out of what distresses him or her. Not knowing these three or four things can weaken the relationship and make it a dangerous place for both of you.