Wired for Love (9 page)

Authors: Stan Tatkin

First, if you find you can’t decide which style best fits your partner or yourself, don’t try to force it. I have presented the styles in their pure form; in reality, the “mileage you get” from this information may vary. Although the vast majority of people do identify with one or another of these three styles, not everyone does. In fact, people can be a blend of different styles, which sometimes makes it difficult to pick the most salient one. If this is the case for you, no worries. You can keep both in mind and use whichever fits best in a given situation.

Second, my purpose in describing these styles is to inspire respect and understanding for what I believe to be normal human traits. Please do not take them as character defects. Definitely don’t turn them into ammunition against your partner. Rather, see these styles as representing the natural and necessary adaptations each of us makes as we develop into adulthood.

How We Develop Our Style of Relating

As I’ve stated, our social wiring is set at an early age. Whether we grow up feeling basically secure or basically insecure is determined by how our parents or caregivers relate to us and to the world. Parents who put a high value on relationship tend to do more to protect their loved ones than do parents who value other things more. They tend to spend more face-to-face and skin-to-skin time with their child; be more curious about and interested in their child’s mind; be more focused, attentive, and attuned to their child’s needs; and generally be more motivated to quickly correct errors or injuries, because they want to restore the goodness of the relationship. In these ways, they create a secure environment for the child.

The dynamics of this early relationship leave their mark at a physiological level. Neuroscientists have observed that children who receive lots of positive attention from adults tend to develop more neural networks than do children deprived of social interaction with adult brains. The primitives and ambassadors of secure children tend to be well integrated, and so these children generally are able to handle their emotions and impulses. Their amygdalae aren’t overcharged and their hypothalamus conducts normal operations and feedback communication with the pituitary and adrenal glands, the other cogs in the threat and stress wheel, turning that system on and off when appropriate. Their dumb vagus and smart vagus are well balanced.

Because of good relationships early in life, secure children tend to have a well-developed right brain and insula, so they are adept at reading faces, voices, emotions, and body sensations, and at getting the overall gist of things. In particular, their orbitofrontal cortex is well developed, with neural connections that provide feedback to their other ambassadors and their primitives. Compared with insecure children, they tend to have more empathy, better moral judgment, greater control over impulses, and more consistent management of frustration. In general, secure children are more resilient to the slings and arrows of social-emotional stress and do far better in social situations.

A secure relationship is characterized by playfulness, interaction, flexibility, and sensitivity. Good feelings predominate because any bad feelings are quickly soothed. It’s a great place to be! It’s a place where we can expect fun and excitement and novelty, but also relief and comfort and shelter. When we experience this kind of secure foundation as a child, we carry it forth into adulthood. We become what I’m calling an anchor.

However, not all of us had relationships in early childhood that felt secure. Perhaps we had several rotating caregivers, without one who was consistently available or dependable. Or perhaps we had one or more caregivers who primarily valued something else more than relationship, such as self-preservation, beauty, youth, performance, intelligence, talent, money, or reputation. Maybe one or more caregivers emphasized loyalty, privacy, independence, and self-sufficiency over relationship fidelity. Almost anything can supplant the value of relationship, and often when this occurs, it is not by choice. A caregiver’s mental or physical illness, unresolved trauma or loss, immaturity, and the like can interfere with a child’s sense of security. If this happens to us, then as adults we come to relationships with an underlying insecurity. That can lead us to keep to ourselves and avoid too much contact, instead viewing ourselves as an island in the ocean of humanity. Or it can lead to ambivalence about connecting with others, in which case we become more like a wave.

Exercise: Take a Snapshot of Your Childhood

As you wonder about your own childhood, you might ask yourself if any of the following happened when you were a child:

- Was I frequently left alone to play by myself?

- Was I taken out as a show item and then put away when no longer needed?

- Was I expected to meet the needs of my caregivers more than my own needs?

- Was I expected to manage my caregivers’ emotional world or self-esteem?

- Was I expected to stay young, cute, and dependent?

- Was I expected to grow up quickly, act self-sufficient, and not be a problem?

- Were my caregivers sensitive to my needs or did they frequently misread me?

Before we go further, I want to clarify that this snapshot of your childhood is not about whether or not you were loved by your parents. I don’t want to give the impression I’m talking about

love

. What I’m describing has less to do with love and more to do with safety and security and the underlying attitudes we bring to a relationship.

Three Styles of Relating

When speaking about attachment styles, psychologists use terms such as

securely attached, insecurely avoidant

, and

insecurely ambivalent

. To keep it a bit lighter here, I’m going to substitute the terms

anchor, island

, and

wave

.

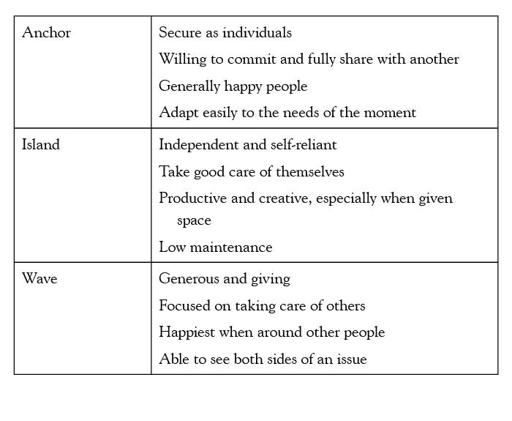

Clearly there are advantages to being an anchor. Given the option, most of us would choose to feel secure over not. But we all bring something different to the table. Imagine what a boring place this world would be if it were any other way. To help you keep this in focus, I’d like to begin by summarizing the strengths of each type, in table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Strengths of the three styles of relating

As you read about the three couples in this chapter and learn more about the three styles, see which style best reflects the relationship styles of yourself and your partner.

The Anchor: “Two Can Be Better than One.”

Mary and Pierce have been together for twenty five years. They raised two children, both now out of the home. These days, Mary and Pierce spend more time dealing with their aging parents than with issues related to their own offspring. When Pierce’s widowed mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, the couple found themselves struggling with the various options. Both have rewarding but demanding careers in the legal field, and as much as they would have liked to bring Pierce’s mother into their home for care, they had to acknowledge that would not be realistic.

Their conversations during the process of arriving at the decision to find a medical facility for Pierce’s mother went something like this.

“I want you to tell me exactly how you feel,” Mary says, looking intently at Pierce so as not to miss any subtle communication written on his face.

“Of course, you know I always do,” says Pierce. “Honestly, since we had that long talk the other night, I have to say I’m feeling a degree of relief.”

“You mean since we discussed moving your mom out of her home?”

“Right.” He pauses, looking deeply into Mary’s eyes, not hiding the pain still hovering beneath his relief. “I think it’s taken a load off me to realize that staying here might not be the best life for her.”

“You know, I was worried you might be upset with me when I first said what I thought would be best,” Mary says quickly. “I wasn’t sure we were on the same page. My parents are still healthy, so this isn’t the same experience for me.”

Pierce smiles. “Yes, I admit I was pretty upset at first. But I thought about it. I knew you were trying to figure out what would be best for all of us—you, me, and my mother.”

“Exactly,” says Mary. “If it were my mom, I’d want the same from you. This isn’t about getting my way. It’s about us, together. If you strongly believe we should find a way to bring your mom here, at least for a while, I’ll work with you on that. I might disagree. But I certainly won’t fight you.”

“Thanks,” says Pierce. “And thanks for not overreacting when I started to get kind of uptight.”

“Honey, I had a pretty good sense of what was happening for you,” Mary says gently, then pauses and continues with a twinkle in her eye. “You know, after all these years, I have the manual on you.”

Pierce smiles back. “You sure do, and I’m so glad—even if it’s a heck of a long manual, with all my quirks and foibles.”

Mary gives a little chuckle. “You know I wouldn’t have you any other way. Besides, the manual you have on me isn’t exactly the abridged version.”

Pierce pauses and sighs deeply. “When I think about it rationally, it’s obvious that it wouldn’t work to bring mom here.”

“Honey, if we put our heads together, we can find ways to make the best of the situation. For example, getting your mom a place that’s close by. And arranging our schedules so we can both visit her as much as possible…” Mary stops because she sees Pierce nodding his head and his eyes tearing up.

“And bring her here for meals as often as we can,” he says, picking up where Mary left off. She wipes a teardrop off his cheek, and he grabs her hand and kisses it. “Actually, I think I’ll feel better once I see my mom well taken care of in a good environment.”

“I know you will,” says Mary. “And we’ll keep talking. Whatever comes up, we’ll deal with it. As we always do, yeah?”

“Yup. You know,” Pierce adds, giving her a hug, “I so appreciate being able to talk with you about all this. We make a good team.”

We Can Do It Together

Mary and Pierce are examples of two anchors. They each came to the relationship feeling secure in themselves as individuals. Of course, anchors don’t always choose to be with other anchors. An anchor can mate with an island or a wave. In many cases, these matches result in the other partner becoming more of an anchor. Let me say this again because it is important: anchors can pull non-anchors into becoming anchors themselves. Of course, the reverse can occur, as well. An island or wave can pull an anchor into becoming more insecure.

As anchors, Mary and Pierce are able to offer this security to one another because they experienced and learned from early caregivers who placed a high value on relationship and interaction. Their parents were attuned, responsive, and sensitive to their signals of distress, bids for comfort, and efforts to communicate. Both Mary and Pierce have memories of being held, hugged, kissed, and rocked as a child. They recall seeing a loving gleam in their parents’ eyes that they knew was meant just for them.

Neither Mary nor Pierce feels the other is overly needy or clings to him or her. And neither feels anxious about getting too close or moving too far away. When they have to be apart for some reason, they make frequent contact by phone and e-mail, greeting each other with liveliness and good cheer. Together or apart, they are unafraid to fully share one another’s minds without concern about any negative consequences, as was the case when Mary made known what she thought would be best for Pierce’s mom. They respect each other’s feelings and treat one another as the first source to share good news and bad news. Each takes careful notice of the other in private and in public, minding cues that signal distress and responding quickly to provide relief. In all these ways, they build a mutual appreciation for their couple bubble and regard themselves as stewards of their mutual sense of safety and security. Each has made the effort to learn how the other works and to compile what amounts to a manual with all this knowledge, and they make use of it on a daily, if not moment-to-moment, basis.

This couple truly view themselves to be in each other’s care, and understand that the lifeline they maintain, their tether to each other, is what gives them the energy and courage needed to face the daily stresses and challenges of the real world. Because their relationship is secure, they are able to continually turn to it and use it as their anchoring device amidst the sometimes chaotic outer world.

Anchors aren’t perfect people, but they are generally happy people. They are given to feelings of gratefulness for the things and people in their lives. People tend to be drawn to anchors because of their strength of character, love of people, and complexity. They adapt easily to the needs of the moment. They can make decisions and bear the consequences.

Anchors take good care of themselves and their relationships. They expect committed partnerships to be mutually satisfying, supportive, and respectful, and will not bother with unsafe or nonreciprocal relationships. They do not give up on a relationship if the going gets rough, or when they become frustrated. They are unafraid to admit errors and are quick to mend injuries or misunderstandings as they arise. They handle moments of togetherness with the same ease as they handle separation from their partner. In these ways, they are good at coping with relationship challenges that might overwhelm non-anchors.