Wired for Love (14 page)

Authors: Stan Tatkin

The two of you can play the Emote Me Game whenever you feel like it. Experiment with different positive effects: make your partner relax, make your partner laugh, or anything else you can think of.

Fourth Guiding Principle

The fourth principle in this book is that

partners who are experts on one another know how to please and soothe each other.

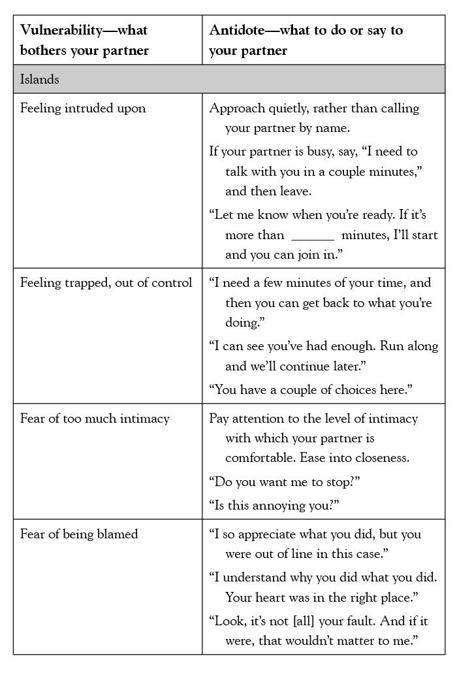

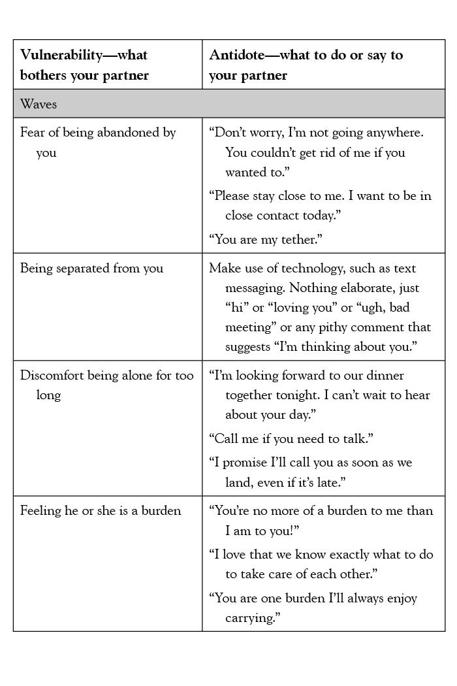

This means becoming familiar with your partner’s primary vulnerabilities and knowing the antidotes that are effective for each. Table 4.2 summarizes some of the typical vulnerabilities for islands and waves we have seen in this chapter and offers suggestions for helping your partner minimize these when they make an appearance. Again, I haven’t included anchors because they tend to be secure and less in need of antidotes.

Table 4.2 What You Can Do to Help Your Partner

Here are some supporting principles to guide you in soothing and pleasing your partner:

- Learn to rapidly repair damage. Being an expert on your partner means you are continually alert to his or her mood and feelings. If your partner is bothered, you know it immediately. It doesn’t matter whether your partner is bothered because of something occurring between the two of you or because of something outside the relationship. In either case, you are enough of an expert that you can speedily make an educated guess about which of his or her three or four bad things has been touched off. There is no reason to let any problems fester. Seeing your partner in distress should be the signal to “stop the presses” before continuing on with

anything.For example, if you think you caused your partner pain, you might say, “That didn’t go well, did it?” or “I’m so sorry. Did that just hurt you?” The worst thing you can do is ignore what you see on your partner’s face or hear in your partner’s voice. Let your partner know he or she can count on you to step up and say or do whatever is needed to repair the damage.

And the same applies to you. You can rely on your partner to be there for you, to know your vulnerabilities and soothe you when you’re upset. It’s as though when you formed your relationship, you took out a policy that would ensure your comfort, and now because you’ve kept up with your premiums (that is, by being there for your partner), you’re able to relax and cash in whenever something seems to have gotten out of hand.

- Prevent problems before they arise. Knowing how to repair damage is helpful, but it is even better to anticipate and avoid difficulties. Of course, it won’t be possible to avert all challenges. Life doesn’t work that way. But as experts, there is a lot you and your partner can do to please and keep each other happy. Rather than waiting until you see trouble brewing, be proactive with your partner. Make a habit of saying and doing the things that make him or her feel good. Don’t assume your partner already knows how much you love him or her; don’t figure you’ve already adequately expressed everything you appreciate about your partner. Find new and creative ways to convey the three or four things that make your partner feel good. In this way, you make deposits you can draw on when the going gets rough.

- You may be wondering, what if my partner and I disagree about what our three or four bad things and three or four good things are? The answer is that it doesn’t really matter. It isn’t actually critical that you correctly identify your own three or four things or know how to scratch your own itch. What’s important is that you know how to do these things with your partner, and vice versa.

So, how do you know if what you’ve come up with for your partner really works? The proof, so to speak, is in the pudding. The evidence will always be visible on your partner’s face, audible in his or her voice, or apparent in his or her spontaneous shift in mood.

There’s no need to get into a debate with your partner about what your three or four things are (bad or good). That’s why I referred to this expertise as a “secret” superpower. Simply respond according to what you understand these good and bad things to be, then sit back and watch the results. If it turns out you’re not seeing the desired results, chances are you are not yet scratching the right itch. In that case, it’s time to go back to the drawing board and learn more about your partner. Through a process of experimentation, of trial and error, you can continue to become a better expert.

Chapter 5

Launchings and Landings: How to Use Morning and Bedtime Rituals

Breakfast in bed. The thrill of birthday and Christmas mornings. Wake-up songs. Wake-up kisses. Perhaps these are some familiar snapshots from your childhood morning rituals. Bedtime stories. Lullabies. Daily debriefings. Being tucked into bed at night. Prayers. Kisses on the forehead. These are all bedtime rituals.

From our earliest beginnings throughout our adult life, we must transition from sleep to wake, and from wake to sleep. We must launch in the morning, and land at night. We learn this during childhood, and the habits we form tend to stay with us. The manner in which we are accustomed to shifting between consciousness and unconsciousness has important consequences for our mental and physical health, as well as for the health of our relationship.

In fact, many people—both singles and couples—have trouble with mornings and nighttimes. Depressed people are sometimes more depressed upon awakening. Facing a new day, especially after a nighttime of upsetting dreams, a person who is depressed may feel unmotivated and fearful and dread getting up. Anxious people are sometimes more anxious at night. While lying in bed, worrisome thoughts, images, and memories tend to fill their mind with vexing internal chatter. The transition between wake and sleep can be so painful for some people that they prefer to simply fall into bed, pass out, and not deal with it at all.

If your partner has any of these troubles, he or she may have sought relief through medication. And for some, this is effective. However, sleeping medications can be addictive or lead to other negative results: difficulty waking; depression; next-day grogginess; rebound insomnia, and even drunken, out-of-control behavior. Worse yet, your partner may be tempted to seek relief through self-medicating activities and substances, such as pornography, chat rooms, online poker, late-night television, alcohol, food, marijuana, or a combination of the aforementioned.

So why have I included a chapter on morning and nighttime rituals as part of this owner’s manual for your partner? Because you can and should be your partner’s best antidepressant and antianxiety agent. And best of all, no insurance reimbursement needed!

As we saw in chapter 4, being an expert on your partner means you know how to please and soothe him or her whenever needed. During infancy, hopefully this kind of soothing was provided by a primary caregiver. If your partner is an anchor, he or she had a secure base from which to explore the environment and return whenever in need of comfort and refueling. If your partner is an island, however, that secure base was relatively unavailable, and now he or she may deny or dismiss the need for a partner to soothe and be there as a source of comfort. After all, why consider the importance of such security if it was never available in the first place?

Studies of children in Israeli kibbutzim, where communal living arrangements meant they were separated at nighttime and early mornings from their mother, give us insight into this question. Attachment theorist John Bowlby (1969) predicted children in such situations would be less secure, and researchers have documented this to be the case. For example, Abraham Sagi and colleagues (1994), who compared children who slept at home with children who slept away from their parents, found that if the parent was consistently unavailable at bedtime, the child was more likely to be insecure. More recently, Liat Tikotsky and her team (2010) reported that parents who experienced communal living as infants were more like to report concerns about their infant’s sleep disturbances. Their study revealed a silver lining, however: these parents also were more likely to soothe their infants at bedtime.

Whether or not your partner felt smoothly transitioned at bedtime and in the morning during childhood, here’s the good news: your partner has the perfect opportunity now to have that secure base again, or for the very first time…with you!

Sleeping and Waking Separately

Noah and Isabella, both in their mid thirties, are raising two young children while working hard at their respective professions. In the early years of marriage, they used to go out together and keep late hours. Now, with child-rearing duties and a mounting financial burden, both are too busy and too exhausted. They have enlisted extended family members to help with various daycare duties, and have a young babysitter on nights when both work late.

When she can, Isabella prefers to go to bed around 9 p.m., as soon as the children are asleep. Noah has always been a night owl, and stays up until at least midnight. Isabella is the only one up early enough to make the children’s breakfast. After that, she runs off to the gym and then to work. Noah typically wakes an hour after she has left the house. They maintain their disparate sleep-wake patterns on weekends, as well.

These partners have become unhappy with one another. Both blame their dissatisfaction on the children, their work, and their financial woes. Noah has become increasingly depressed and anxious, and Isabella is resentful of his complaining. Neither looks to their lack of togetherness at bedtime and waking as a problem. Yet each complains of waning energy, powerlessness, and a growing sense of hopelessness about the marriage.

What effect do you think Isabella going to bed early has on Noah? What effect does the sight of an empty bed have on Isabella when she briefly wakes at 1 a.m.? What effect does waking alone in the morning have on both partners?

When living alone, we may not be bothered by the sight of an empty bed. However, when we live with a partner, we become accustomed to having him or her next to us—preferably awake while we are awake, and asleep while we are asleep. Whether we are aware of it or not, we may react to an empty bed when we expect someone to be there. Even if we know it is only a temporary separation, the experience that our partner has left us can be unsettling. Isabella has island qualities and appreciates her time alone, yet she sometimes finds it hard to fall back to sleep after waking to find Noah still up. And Noah, who has wave tendencies, sometimes feels abandoned when Isabella goes to bed before he does, even though he is naturally a night owl.

To complicate matters, their respective genders may influence Isabella’s and Noah’s sleep experience. In fact, various studies have shown that men and women not only have different sleep patterns, but perceive their experience differently. For example, John Dittami and colleagues (2007) compared couples when they slept alone and when they slept together over a period of twenty eight nights. They found that women had more disrupted sleep when they were with a partner than when they slept alone, while men reported enjoying sleeping together more than women did.

Wendy Troxel (2010) pointed out a paradox emerging from this field of research. On the one hand, measures of the biophysiological changes that occur during sleep (e.g., reaching the most restful level of sleep—called level 4 sleep; having fewer body movements) indicate that, overall, couples sleep better alone. On the other hand, couples subjectively report that they sleep better when they are together. She theorizes that, for both men and women, the need to feel secure at night outweighs any sleep disturbances that may accompany cosleeping. This would explain, for instance, why Isabella is disturbed when she wakes to an empty bed. It also supports what I stress in the guiding principles of this book: the importance of keeping your partner safe and secure.

It’s also possible that Isabella and Noah are influenced by their respective circadian rhythms—the daily biological cycle that determines when an individual is inclined to eat, sleep, and perform other actions. Research has shown that couples with different rhythms, such as night owls paired with early birds, can experience instability in their relationships. For example, Jeffry Larson and team (Larson, Crane, and Smith 1991) found that couples with different night and morning orientations had more arguments than did similarly oriented couples, and spent less quality time together. It’s actually common for couples to have different daily rhythms, yet I believe it’s possible and even healthy for these partners to get onto the same sleep schedule, or at least to create ways to begin and end the day together. You can improve your relationship if you make the effort to coordinate sleep/wake patterns with your partner.