Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (25 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Figure 3.36

Female reproductive organs and other structures in the pelvic cavity.

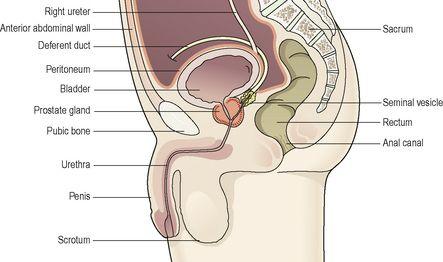

Figure 3.37

The pelvic cavity and reproductive structures in the male.

Contents

The pelvic cavity contains the following structures:

•

sigmoid colon, rectum and anus

•

some loops of the small intestine

•

urinary bladder, lower parts of the ureters and the urethra

•

in the female, the organs of the reproductive system: the uterus, uterine tubes, ovaries and vagina (

Fig. 3.36

)

•

in the male, some of the organs of the reproductive system: the prostate gland, seminal vesicles, spermatic cords, deferent ducts (vas deferens), ejaculatory ducts and the urethra (common to the reproductive and urinary systems) (

Fig. 3.37

).

Disorders of cells and tissues

Learning outcomes

After studying this section you should be able to:

outline the common causes of tumours

explain the terms ‘well differentiated’ and ‘poorly differentiated’

outline causes of death in malignant disease

compare and contrast the effects of benign and malignant tumours.

Neoplasms or tumours

A tumour or

neoplasm

(literally meaning ‘new growth’) is a mass of tissue that grows faster than normal in an uncoordinated manner, and continues to grow after the initial stimulus has ceased.

Tumours are classified as benign or malignant although a clear distinction is not always possible (see

Table 3.2

). Benign tumours only rarely change their character and become malignant. Tumours may be classified according to their tissue of origin. For example, an

adenoma

is a benign tumour of glandular tissue whereas an

adenocarcinoma

is a malignant tumour of glandular or secretory epithelial tissue. Malignant tumours are often named according to the tissue they arise from, for example a

carcinoma

originates in epithelial tissue whereas a

sarcoma

arises from connective tissue.

Table 3.2

Typical differences between benign and malignant tumours

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

| Slow growth | Rapid growth |

| Cells well differentiated (resemble tissue of origin) | Cells poorly differentiated (may not resemble tissue of origin) |

| Usually encapsulated | Not encapsulated |

| No distant spread (metastases) | Spreads (metastasises): – by local infiltration – via lymph – via blood – via body cavities |

| Recurrence is rare | Recurrence is common |

Causes of neoplasms

Some factors are known to trigger neoplastic changes in cells but the reasons for the uncontrolled cell multiplication are not known. The process of change is

carcinogenesis

and the agents precipitating the change are

carcinogens

. Carcinogenesis may be of genetic and/or environmental origin and a clear-cut distinction is not always possible.

Carcinogens

Environmental agents known to cause malignant changes in cells do so by irreversibly damaging a cell’s DNA. It is impossible to specify a maximum ‘safe dose’ of a carcinogen. A small dose may initiate change but this may not be enough to cause malignancy unless there are repeated doses within a limited period of time that have a cumulative effect. In addition, there are widely varying latent periods between exposure and evidence of malignancy. There may also be other unknown factors. Environmental carcinogens include chemicals, irradiations and oncogenic viruses.

Chemical carcinogens

Some chemicals are carcinogens when absorbed; others are modified after absorption and become carcinogenic. Examples include:

•

aniline dyes, which predispose to bladder cancer (

p. 348

)

•

asbestos, which is associated with malignant pleural tumours (mesothelioma,

p. 262

)

•

cigarette smoke, which is the main risk factor for lung cancer (

p. 262

).

Ionising radiation

Exposure to ionising radiation including X-rays, radioactive isotopes, environmental radiation and ultraviolet rays in sunlight may cause malignant changes in some cells and kill others. The cells are affected during mitosis so those normally undergoing continuous controlled division are most susceptible. These labile tissues include skin, mucous membrane, bone marrow, lymphoid tissue and gametes in the ovaries and testes.

Oncogenic viruses

Some viruses are known to cause malignant changes in animals and there are indications of similar involvement in humans. Viruses enter cells and incorporate their DNA or RNA into the host cell’s genetic material, which causes mutation. The mutant cells may be malignant. Examples include hepatitis B virus, which can cause liver cancer (

p. 326

) and human papilloma virus, which is associated with cervical cancer (

p. 453

).

Host factors

Individual characteristics can influence susceptibility to tumours. These include race, diet, age, obesity and inherited (genetic) factors. Tumours of individual tissues and organs are described in the appropriate chapters.

Growth of tumours

Normally cells divide in an orderly manner. Neoplastic cells have escaped from the normal controls and they multiply in a disorderly and uncontrolled manner forming a tumour. Blood vessels grow with the proliferating cells, but in some malignant tumours the blood supply does not keep pace with growth and

ischaemia

(lack of blood supply) leads to tumour cell death, called

necrosis

. If the tumour is near the surface, this may result in skin ulceration and infection. In deeper tissues there is fibrosis; e.g. retraction of the nipple in breast cancer is due to the shrinkage of fibrous tissue in a necrotic tumour. The mechanisms controlling the life span of tumour cells are poorly understood.

Cell differentiation

Differentiation of cells into specialised cell types with particular structural and functional characteristics occurs at an early stage in fetal development, e.g. epithelial cells develop different characteristics from lymphocytes. Later, when cell replacement occurs, daughter cells have the same appearance, functions and genetic make-up as the parent cell. In benign tumours the cells from which they originate are easily recognised, i.e. tumour cells are

well differentiated

. Tumours with well-differentiated cells are usually benign but some may be malignant. Malignant tumours grow beyond their normal boundaries and show varying levels of differentiation: