Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (20 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

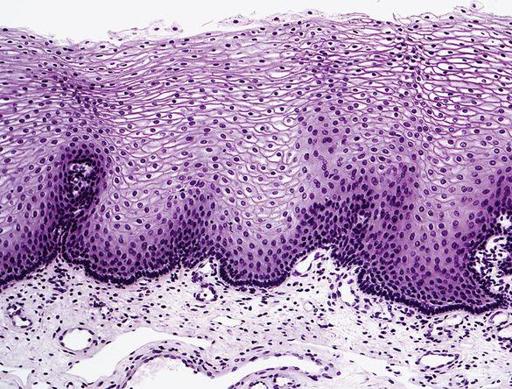

Figure 3.14

Section of non-keratinised stratified squamous epithelial lining of the vagina (magnified × 100).

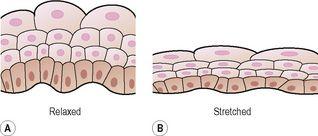

Transitional epithelium (

Fig. 3.15

)

This is composed of several layers of pear-shaped cells. It is found lining the urinary bladder and allows for stretching as the bladder fills.

Figure 3.15

Transitional epithelium: A.

Relaxed.

B.

Stretched.

C.

Light micrograph of bladder wall showing transitional epithelium (pink) above smooth muscle and connective tissue layer (red).

Connective tissue

Connective tissue is the most abundant tissue in the body. The connective tissue cells are more widely separated from each other than in epithelial tissues, and intercellular substance (matrix) is present in considerably larger amounts. There are usually fibres present in the matrix, which may be of a semisolid jelly-like consistency or dense and rigid, depending upon the position and function of the tissue. The fibres form a supporting network for the cells to attach to. Most types of connective tissue have a good blood supply. Major functions of connective tissue are:

•

binding and structural support

•

protection

•

transport

•

insulation.

Cells in connective tissue

Connective tissue, excluding blood (see

Ch. 4

), is found in all organs supporting the specialised tissue. The different types of cell involved include: fibroblasts, fat cells, macrophages, leukocytes and mast cells.

Fibroblasts

Fibroblasts are large cells with irregular processes (

Fig. 3.5

). They produce

collagen

and

elastic fibres

and a matrix of extracellular material. Very fine collagen fibres, sometimes called

reticulin fibres

, are found in very active tissue, such as the liver and lymphoid tissue. Fibroblasts are particularly active in tissue repair (wound healing) where they may bind together the cut surfaces of wounds or form

granulation tissue

following tissue destruction (see

p. 359

). The collagen fibres formed during healing shrink as they grow old, sometimes interfering with the functions of the organ involved and with adjacent structures.

Fat cells

Also known as

adipocytes

, these cells occur singly or in groups in many types of connective tissue and are especially abundant in adipose tissue (see

Fig. 3.17B

). They vary in size and shape according to the amount of fat they contain.

Macrophages

These are irregular-shaped cells with granules in the cytoplasm. Some are fixed, i.e. attached to connective tissue fibres, and others are motile. They are an important part of the body’s defence mechanisms because they are actively phagocytic, engulfing and digesting cell debris, bacteria and other foreign bodies. Their activities are typical of those of the macrophage/monocyte defence system, e.g. monocytes in blood, phagocytes in the alveoli of the lungs, Kupffer cells in liver sinusoids, fibroblasts in lymph nodes and spleen, and microglial cells in the brain.

Leukocytes

White blood cells (

p. 61

) are normally found in small numbers in healthy connective tissue but neutrophils migrate in significant numbers during infection when they play an important part in tissue defence.

Plasma cells

These develop from B-lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell (see

p. 61

). They synthesise and secrete specific defensive

antibodies

into the blood and tissues (see

Ch. 15

).

Mast cells

These cells are similar to basophil leukocytes (see

p. 62

). They are found in loose connective tissue and under the fibrous capsule of some organs, e.g. liver and spleen, and in considerable numbers round blood vessels. They produce granules containing

heparin

,

histamine

and other substances, which are released when the cells are damaged by disease or injury. Histamine is involved in local and general inflammatory reactions, it stimulates the secretion of gastric juice and is associated with the development of allergies and hypersensitivity states (see

p. 374

). Heparin prevents coagulation of blood, which may aid the passage of protective substances from blood to affected tissues.

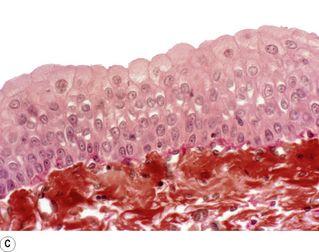

Loose (areolar) connective tissue (

Fig. 3.16

)

This is the most generalised type of connective tissue. The matrix is semisolid with many fibroblasts and some fat cells (adipocytes), mast cells and macrophages widely separated by elastic and collagen fibres. It is found in almost every part of the body, providing elasticity and tensile strength. It connects and supports other tissues, for example:

•

under the skin (

Fig. 3.16B

)

•

between muscles

•

supporting blood vessels and nerves

•

in the alimentary canal

•

in glands supporting secretory cells.

Figure 3.16

Loose (areolar) connective tissue. A.

Diagram of basic structure.

B.

Coloured scanning electron micrograph of fat cells surrounded by strands of connective tissue.

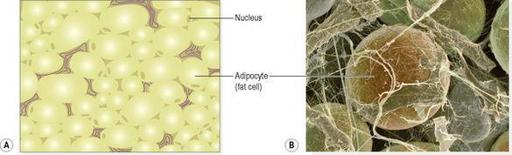

Adipose tissue (

Fig. 3.17

)

Adipose tissue consists of fat cells (adipocytes), containing large fat globules, in a matrix of areolar tissue (

Fig. 3.16

). There are two types: white and brown.

Figure 3.17

Adipose tissue. A.

Diagram of basic structure.

B.

Coloured scanning electron micrograph of fat cells surrounded by strands of connective tissue.

White adipose tissue

This makes up 20 to 25% of body weight in well-nourished adults. The amount of adipose tissue in an individual is determined by the balance between energy intake and expenditure. It is found supporting the kidneys and the eyes, between muscle fibres and under the skin, where it acts as a thermal insulator and energy store.

Brown adipose tissue

This is present in the newborn. It has a more extensive capillary network than white adipose tissue. When brown tissue is metabolised, it produces less energy and considerably more heat than other fat, contributing to the maintenance of body temperature. In some adults it is present in small amounts.

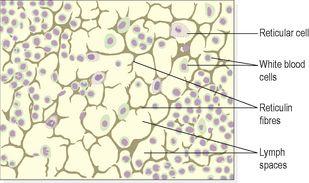

Lymphoid tissue (

Fig. 3.18

)

This tissue, also known as reticular tissue, has a semisolid matrix with fine branching reticulin fibres. It contains reticular cells and white blood cells (

monocytes

and

lymphocytes

). Lymphoid tissue is found in lymph nodes and all organs of the lymphatic system (see

Fig. 6.1, p. 128

).

Figure 3.18

Lymphoid tissue.

Dense connective tissue

This contains more fibres and fewer cells than loose connective tissue.

Fibrous tissue (

Fig. 3.19A

)

This tissue is made up mainly of closely packed bundles of collagen fibres with very little matrix. Fibrocytes (old and inactive fibroblasts) are few in number and are found lying in rows between the bundles of fibres. Fibrous tissue is found:

•

forming

ligaments

, which bind bones together