Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (30 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Leukocytes (white blood cells)

These cells have an important function in defence and immunity. Leukocytes are the largest blood cells but they account for only about 1% of the blood volume. They contain nuclei and some have granules in their cytoplasm (

Table 4.2

). There are two main types:

•

granulocytes (polymorphonuclear leukocytes)

–

neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils

•

agranulocytes

–

monocytes and lymphocytes.

Table 4.2

Normal leukocyte counts in adult blood

| | Number x 10 9 /l | Percentage of total |

|---|---|---|

| Granulocytes | ||

| Neutrophils | 2.5 to 7.5 | 40 to 75 |

| Eosinophils | 0.04 to 0.44 | 1 to 6 |

| Basophils | 0.015 to 0.1 | < 1 |

| Agranulocytes | ||

| Monocytes | 0.2 to 0.8 | 2 to 10 |

| Lymphocytes | 1.5 to 3.5 | 20 to 50 |

| Total | 5 to 9 | 100 |

Rising white cell numbers in the bloodstream usually indicate a physiological problem, e.g. infection, trauma or malignancy.

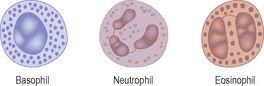

Granulocytes (polymorphonuclear leukocytes)

During their formation,

granulopoiesis

, they follow a common line of development through

myeloblast

to

myelocyte

before differentiating into the three types (

Figs 4.2

and

4.8

). All granulocytes have multilobed nuclei in their cytoplasm. Their names represent the dyes they take up when stained in the laboratory. Eosinophils take up the red acid dye, eosin; basophils take up alkaline methylene blue; and neutrophils are purple because they take up both dyes.

Figure 4.8

The granulocytes (granular leukocytes).

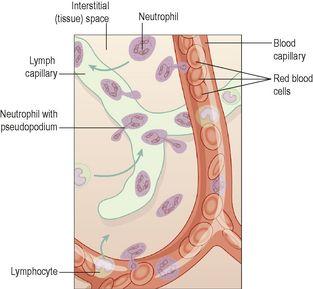

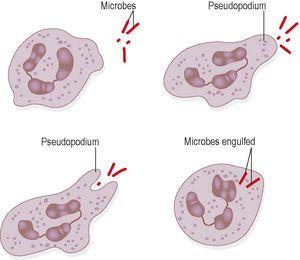

Neutrophils

These small, fast and active scavengers protect the body against bacterial invasion, and remove dead cells and debris from damaged tissues. They are attracted in large numbers to any area of infection by chemical substances called

chemotaxins

, which are released by damaged cells. Neutrophils are highly mobile, and squeeze through the capillary walls in the affected area by

diapedesis

(

Fig. 4.9

). Their numbers rise very quickly in an area of damaged or infected tissue. Once there, they engulf and kill bacteria by

phagocytosis

(

Fig. 4.10

). Their nuclei are characteristically complex, with up to six lobes, and their granules are

lysosomes

containing enzymes to digest engulfed material. Neutrophils live on average 6–9 hours in the bloodstream. Pus that may form in an infected area consists of dead tissue cells, dead and live microbes, and phagocytes killed by microbes.

Figure 4.9

Diapedesis of leukocytes.

Figure 4.10

Phagocytic action of neutrophils.

Eosinophils

Eosinophils, although capable of phagocytosis, are less active in this than neutrophils; their specialised role appears to be in the elimination of parasites, such as worms, which are too big to be phagocytosed. They are equipped with certain toxic chemicals, stored in their granules, which they release when the eosinophil binds to an infecting organism.

Eosinophils are often found at sites of allergic inflammation, such as the asthmatic airway and skin allergies. There, they promote tissue inflammation by releasing their array of toxic chemicals, but they may also dampen down the inflammatory process through the release of other chemicals, such as an enzyme that breaks down histamine (

p. 368

).

Basophils

Basophils, which are closely associated with allergic reactions, contain cytoplasmic granules packed with

heparin

(an anticoagulant),

histamine

(an inflammatory agent) and other substances that promote inflammation. Usually the stimulus that causes basophils to release the contents of their granules is an

allergen

(an antigen that causes allergy) of some type. This binds to antibody-type receptors on the basophil membrane. A cell type very similar to basophils, except that it is found in the tissues, not in the circulation, is the

mast cell

. Mast cells release their granule contents within seconds of binding an allergen, which accounts for the rapid onset of allergic symptoms following exposure to, for example, pollen in hay fever (

p. 374

).

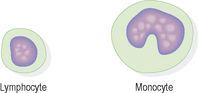

Agranulocytes

The

monocytes

and

lymphocytes

make up 25 to 50% of the total leukocyte count (

Figs 4.2

and

4.11

). They have a large nucleus and no cytoplasmic granules.

Figure 4.11

The agranulocytes.

Monocytes

These are the largest of the white blood cells. Some circulate in the blood and are actively motile and phagocytic while others migrate into the tissues where they develop into

macrophages

. Both types of cell produce

interleukin

1, which:

•

acts on the hypothalamus, causing the rise in body temperature associated with microbial infections

•

stimulates the production of some globulins by the liver

•

enhances the production of activated T-lymphocytes.

Macrophages have important functions in inflammation (

p. 367

) and immunity (

Ch. 15

).

The monocyte–macrophage system

This is sometimes called the

reticuloendothelial system

, and consists of the body’s complement of monocytes and macrophages. Some macrophages are mobile, whereas others are fixed, providing effective defence at key body locations. Collections of fixed macrophages include:

•

synovial cells

in joints

•

Langerhans cells

in the skin

•

microglia

in the brain

•

hepatic macrophages

(Kupffer cells) in the liver

•

alveolar macrophages

in the lungs

•

sinus

-

lining macrophages

(reticular cells) in the spleen, lymph nodes and thymus gland

•

mesangial cells

in the glomerulus of nephrons in the kidney

•

osteoclasts

in bone.

Macrophages have a diverse range of protective functions. They are actively phagocytic and are much more powerful and longer-lived than the smaller neutophils. They synthesise and release an array of biologically active chemicals, called

cytokines

, including interleukin 1 mentioned earlier. They also have a central role linking the non-specific and specific (immune) systems of body defence (

Ch. 15

), and produce factors important in inflammation and repair. They can ‘wall off’ indigestible pockets of material, isolating them from surrounding normal tissue. In the lungs, for example, resistant bacteria such as tuberculosis bacilli and inhaled inorganic dusts can be sealed off in such capsules.

Lymphocytes

Lymphocytes are smaller than monocytes and have large nuclei. They circulate in the blood and are present in great numbers in lymphatic tissue such as lymph nodes and the spleen. Lymphocytes develop from pluripotent stem cells in red bone marrow and from precursors in lymphoid tissue, then travel in the blood to lymphoid tissue elsewhere in the body where they are

activated

, i.e. they become immunocompetent which means they are able to respond to

antigens

(foreign material). Examples of antigens include:

•

cells regarded by lymphocytes as abnormal, e.g. cells that have been invaded by viruses, cancer cells, transplanted tissue

•

pollen from flowers and plants

•

fungi

•

bacteria

•

some large molecule drugs, e.g. penicillin, aspirin.

Although all lymphocytes originate from one type of stem cell, when they are activated in lymphatic tissue, two distinct types of lymphocyte are produced –

T-lymphocytes

and

B-lymphocytes

. The specific functions of these two cell types are discussed in

Chapter 15

.