Writing Tools (3 page)

Authors: Roy Peter Clark

Begin with a good quote. Hide the attribution in the middle. End with a good quote.

Some teachers refer to this as the

2-3-1 tool of emphasis,

where the most emphatic words or images go at the end, the next most emphatic at the beginning, and the least emphatic in the middle, but that's too much calculus for my brain. Here's my simplified version: put your best stuff near the beginning and at the end; hide weaker stuff in the middle.

Amy Fusselman provides an example with the first sentence of her novel,

The Pharmacist's Mate:

"Don't have

sex on a boat

unless you want to

get pregnant."

The most intriguing words come near the beginning and at the end. Gabriel Garcia Marquez uses this strategy at the opening of

One Hundred Years of Solitude

to dazzling effect: "Many years later,

as he faced the firing squad,

Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to

discover ice."

What applies to the sentence also applies to the paragraph, as Alice Sebold demonstrates in this passage:

"In the tunnel where I was raped,

a tunnel that was once an underground entry to an amphitheater, a place where actors burst forth from underneath the seats of a crowd, a girl had been murdered and dismembered. I was told this story by the police. In comparison, they said, I was

lucky."

That final word resonates with such pain and power that Sebold turns it into the title of her memoir,

Lucky.

These tools of emphasis are as old as rhetoric itself. Near the end of Shakespeare's famous tragedy, a character announces to Macbeth: "The Queen, my lord, is dead." This astonishing example of the power of emphatic word order is followed by one of the darkest passages in all of literature. Macbeth says:

She should have died hereafter;

There would have been a time for such a word.

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow Creeps in this petty pace from day to day, To the last syllable of recorded time; And all our yesterdays have lighted fools The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle! Life's but a walking shadow, a poor player That struts and frets his hour upon the stage And then is heard no more. It is a tale Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing.

The poet has one great advantage over those who write prose. He knows where the line will end. He gets to emphasize a word at the end of a line, a sentence, a paragraph. We prose writers make do with the sentence and the paragraph — signifying something.

WORKSHOP

1. Read Lincoln's Gettysburg Address and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech and study emphatic word order.

2. With a pencil in hand, read an essay you admire. Circle the first and last words in each paragraph.

3. Do the same for recent examples of your work. Revise sentences so that powerful and interesting words, which may be hiding in the middle, appear near the beginning and at the end.

4. Survey your friends to get the names of their dogs. Write these in alphabetical order. Imagine that this list appears in a story. Play with the order of the names. Which should go first? Which last? Why?

President John F. Kennedy testified that a favorite book was

From Russia with Love,

the 1957 James Bond adventure by Ian Fleming. This choice revealed more about JFK than we knew at the time and created a cult of 007 that persists to this day.

The power of Fleming's prose flows from active verbs. In sentence after sentence, page after page, England's favorite secret agent, or his beautiful companion, or his villainous adversary, performs the action of the verb (the emphasis is mine):

Bond

climbed

the few stairs and

unlocked

his door and

locked

and

bolted

it behind him. Moonlight

filtered

through the curtains. He

walked

across and

turned

on the pink-shaded lights on the dressing-table. He

stripped

off his clothes and

went

into the bathroom and

stood

for a few minutes under the shower.... He

cleaned

his teeth and

gargled

with a sharp mouthwash to get rid of the taste of the day and

turned

off the bathroom light and

went

back into the bedroom....

Bond

gave

a shuddering yawn. He

let

the curtains drop back into place. He

bent

to switch off the lights on the dressing-table. Suddenly he

stiffened

and his heart

missed

a beat.

There had been a nervous giggle from the shadows at the back of the room. A girl's voice

said,

"Poor Mister Bond. You must be tired. Come to bed."

In writing this passage, Fleming followed the advice of his countryman George Orwell, who wrote of verbs: "Never use the passive where you can use the active."

I learned the distinction between active and passive voice as early as fifth grade. Thank you, Sister Katherine William. I failed to learn, until much later, why that distinction mattered. But let me first correct a popular misconception. The voice of verbs (active or passive) has nothing to do with the tense of verbs. Writers sometimes ask, "Is it ever OK to write in the passive tense?"

Tense

defines action within time —

when

the verb happens — the present, past, or future.

Voice

defines the relationship between subject and verb — who does what.

• If the subject performs the action of the verb, we call the verb

active.

• If the subject receives the action of the verb, we call the verb

passive.

• A verb that is neither active nor passive is a

linking verb,

a form of the verb

to be.

All verbs, in any tense, fit into one of those three baskets.

News writers reach often for the simple active verb. Consider this

New York Times

lead by Carlotta Gall on the suicidal desperation of Afghan women:

Waiflike, draped in a pale blue veil, Madina, 20,

sits

on her hospital bed, bandages covering the terrible, raw burns on her neck and chest. Her hands

tremble.

She

picks

nervously at the soles of her feet and confesses that three months earlier she

set

herself on fire with kerosene.

Both Fleming and Gall use active verbs to power their narratives, but notice an important difference between them. While Fleming uses the past tense to narrate his adventure, Gall prefers the present. This strategy immerses readers in the immediacy of experience, as if we were sitting — right now — beside the poor woman in her grief.

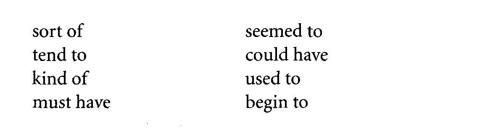

Both Fleming and Gall avoid verb qualifiers that attach themselves to standard prose like barnacles to the hull of a ship:

Scrape away these crustaceans during revision, and the ship of your prose will glide toward meaning with speed and grace.

The earnest writer can overuse a writing tool. If you shoot up your verbs with steroids, you risk creating an effect that poet Donald Hall derides as "false color," the stuff of adventure magazines and romance novels. Temperance controls the impulse to overwrite.

In

The Joy Luck Club,

novelist Amy Tan exercises exquisite control, using strong verbs to depict the authentic color of emotional truth:

And in my memory I can still

feel

the hope that

beat

in me that night. I

clung

to this hope, day after day, night after night, year after year. I would

watch

my mother lying in her bed, babbling to herself as she

sat

on the sofa. And yet I

knew

that this, the worst possible thing, would one day

stop.

I still

saw

bad things in my mind, but now I

found

ways to change them. I still

heard

Mrs. Sorci and Teresa having terrible fights, but I

saw

something else.... I

saw

a girl complaining that the pain of not being seen was unbearable.

Ian Fleming's verbs describe external action and adventure; Amy Tan's verbs capture internal action and emotion. But action can also be intellectual, in the force and power of an argument, as Albert Camus demonstrates in

The Rebel:

The metaphysical rebel

protests

against the condition in which he

finds

himself as a man. The rebel slave

affirms

that there is something in him that will not

tolerate

the manner in which his master

treats

him; the metaphysical rebel

declares

that he is frustrated by the universe.

Notice that even with all the active verbs in that passage, Camus does not pass on the passive when he needs it ("he is frustrated"), which brings us to the next tool.

WORKSHOP

1. Verbs fall into three categories: active, passive, and forms of the verb

to be.

Review your writing and circle verb forms with a pencil. In the margins, categorize each verb.

2. Convert passive and

to be

verbs into the active. For example, "It was her observation that" can become "She observed."

3. In your own work and in the newspaper, search for verb qualifiers and see what happens when you cut them.